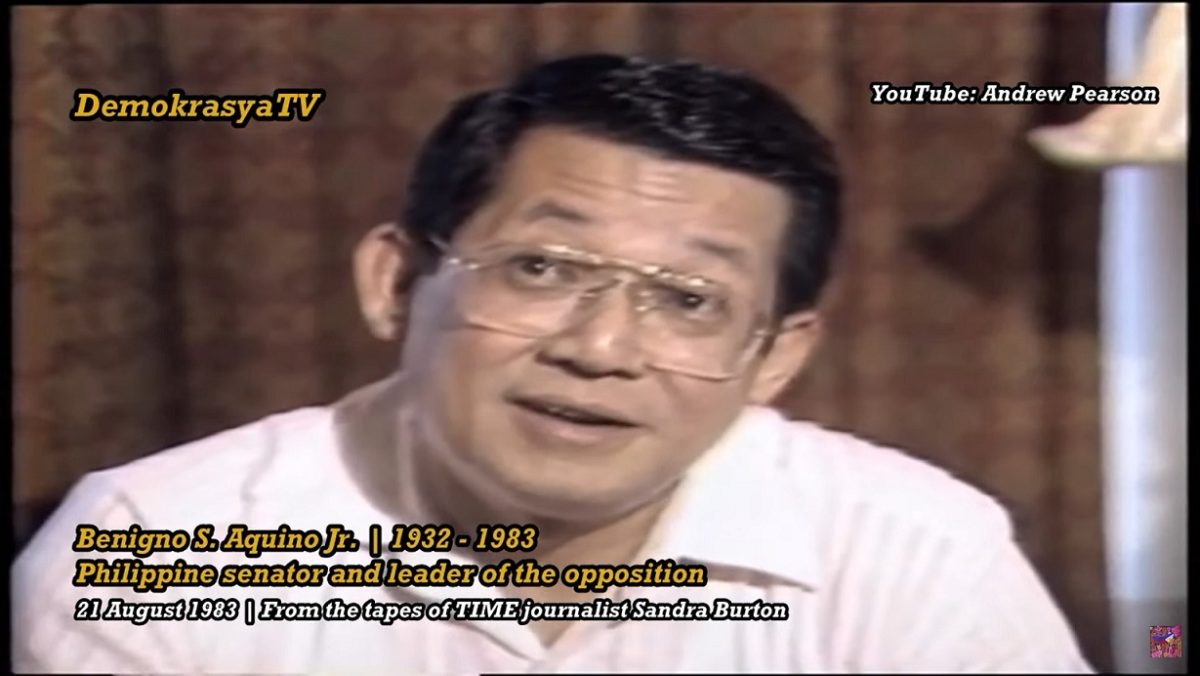

August 21, 2022 is the first Ninoy Aquino Day to be observed under the administration of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. Based on social media posts, Marcos loyalists are, of course, not keen on commemorating the legally declared holiday which marks the assassination of the former senator and main political rival of the Chief Executive’s father.

They echo claims long made by supporters of the former dictator: Aquino was a power-hungry communist; Marcos Sr. had nothing to do with his death 39 years ago; and that Aquino’s widow and son, who both became presidents, should have sought the truth behind the murder but, for some conspiratorial reason, did not.

When Aquino was shot dead while being escorted by uniformed men at the airport after returning from the United States in 1983, Marcos and some of his military men were put in a defensive position. The crime committed in broad daylight triggered a torrent of protests condemning the regime, especially from the business sector and the Church hierarchy, and deeply impacted its credibility at home and abroad.

The former dictator did everything in his power to ensure that he and some of his most loyal men would appear to be free of any culpability for the crime. Marcos put Gregorio Cendaña, his information minister and chief propagandist, to work.

Three days after the Aquino assassination, Marcos created a fact-finding commission to investigate the crime. But the five-member panel, led by then Supreme Court Chief Justice Enrique Fernando, was short-lived as its members resigned due to public outcry over the composition of the commission. By virtue of Presidential Decree No. 1886, another fact-finding team led by the retired associate justice of the Court of Appeals Corazon Agrava was constituted to investigate the murder.

An attempt at manipulating public opinion

Approaching the first anniversary of the assassination, Cendaña had outlined a government communications strategy to match the planned activities of the political opposition as the Agrava Board, which the fact-finding commission came to be known, was about to release its reports.

In a memorandum, the minister informed Marcos that the National Media Production Center (NMPC) and the Philippine News Agency (PNA) would field photographers and video teams to cover public demonstrations from August 17-22, 1984. PNA would write a calendar story on the “official version” of the assassination, which meant the military version that it was a lone civilian assassin, Rolando Galman, who shot Aquino as part of a communist conspiracy.

The plan further stipulated, “[w]e are preparing column feeds on the Aquino statue and the ‘eternal flame’ in Makati, generally ridiculing efforts by anti-government groups’ effort to cast Ninoy prematurely as a national hero” (emphasis from the original document). Cendana said that his agency had been “coordinating with private TV networks to ensure that commercial programming for August 20 and 21 will be particularly interesting—to induce people to stay at home and watch, instead of going out on the streets.” Utilizing the state’s intelligence machinery, the information agency also prepared to circulate “black” leaflets during this period.

The Manila Sun by VERA Files on Scribd

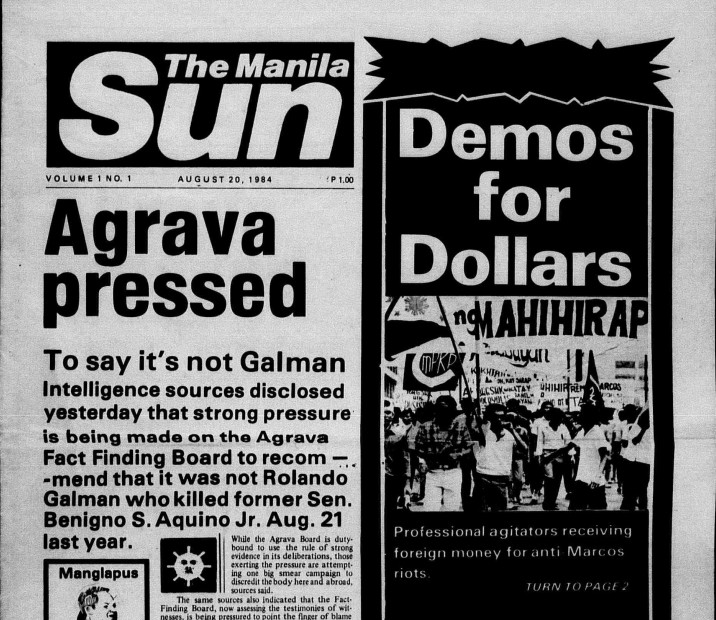

Cendana’s memorandum included an attachment, the first issue of “our own tabloid,” The Manila Sun. Nowhere in the paper, however, did it say that it was published by the Office of the Media Affairs (OMA), NMPC , or any government-controlled agency. Cendaña wrote that “the first issues carries (sic) lead stories on the Agrava case and the clandestine foreign funding for opposition demos and riots.”

The Manila Sun headlined that according to “intelligence sources,” a certain group was forcing the Agrava Board “to recommend that it was not Galman who killed” Aquino and was waging “one big smear campaign to discredit the body here and abroad.”

The article included statements from three lawyers who worked under the Office of the Government Corporate Counsel. Manuel M. Lazaro, Virgilio C. Abejo, and Expedito D. Tan reportedly said that the memorandum sent by the fact-finding board indicated that it was Galman who killed Aquino on orders by the New People’s Army (we know now that the Board unanimously rejected this theory). The lawyers were also reported to have said that “the government exhausted all measures to protect the life of the late senator from persons bent on harming him,” that “the groups aiming to liquidate Aquino included persons who wanted to take revenge on him for the ‘killings of their relatives by you [Aquino] and your [Aquino’s] men.’”

Lazaro, Abejo, and Tan also listed several instances when Marcos Sr. and his wife, Imelda, showed mercy and saved the former senator’s life — the reopening of Aquino’s case after he had been convicted of criminal offenses, their “timely intervention” when Aquino went on a hunger strike in his military cell, and the health care provided him at the Philippine Heart Center for Asia when he was suffering from a heart ailment.

The headline story was bolstered by an opinion piece with the title “The Task At Hand.” The anonymous writer said, “The pressures brought on the (Agrava) board are therefore malicious, tantamount to obstructing the board from its sworn task to flush out the truth, with substantial evidence as the only yardstick.”

Another article entitled “Demos for Dollars” claimed that a “foreign-based” group connected with Kilusan ng mga Demokratikong Pilipino was responsible for the slew of protests in the country at the time. Citing “intelligence reports,” the article said that “student ranks and those of the labor groups were infiltrated by elements from the dissident movement and other radical groups which seek to sow terror and spark an unarmed urban warfare in order to topple the present government.”

Highly-conscious about his image in the United States, Marcos Sr.’s state machinery closely monitored the negative publicity that his administration was receiving abroad. In a memorandum dated August 22, 1984, Cendaña updated his boss about the reportage in U.S. media about the Aquino affair. The information minister shared that major publications (New York Times, Philadelphia Inquirer, Newsday, and Boston Globe) as well as TV and radio stations mentioned the assassination and reported about the demonstrations in Manila.

He also alluded to an article written by opposition leader Raul Manglapus in the New York Times on August 21, 1984 entitled “To Honor Aquino, Drop Marcos.” In response to the piece, Cendaña told Marcos that “our New York information staff prepared a rejoinder signed by Amb. Rey Arcilla of the U.N. (United Nations) Mission.” The response signed by the Filipino diplomat noticeably focused on poisoning the well, calling Manglapus a “discredited politician,” a “steak commando” and a “political has-been.”

The Marcos regime was also in the business of spying on opposition leaders in order to monitor and influence the narrative on the Aquino assassination in the U.S. In a memorandum to Marcos with the subject line “Butz Aquino’s Appearances in the U.S.” dated March 15, 1984, Cendaña briefed Marcos on the highlights of the remarks of the former senator’s younger brother before the Ninoy Aquino Movement (NAM) in Chicago and the National Press Club in Washington.

In his speeches, Butz, who had by then become a prominent opposition leader, reportedly declared that the Aquino family did not recognize the Agrava Board. He also cast doubts on the integrity of the upcoming election and advocated a boycott. As relayed in the memo, Butz reportedly said that “even before the people cast their votes, the results are already known.” Cendaña then told Marcos that “based on the information material we furnished them, our attaches abroad have prepared materials to counter (Butz) Aquino’s claim. The rejoinder will be sent to Filipino civic organizations in the areas.”

The Agrava Board findings

After almost a year into its probe, the Agrava Board submitted its reports to Marcos in October 1984. The five-member panel was unanimous in rejecting the version blaming Galman for Aquino’s murder, concluding instead that the assassination was the result of a military conspiracy. But the panel members disagreed on the extent of the plot.

The majority report, which represented the opinion of four Board members (Luciano Salazar, Dante Santos, Ernesto Herrera, and Amando Dizon) accused 26 people, including then Armed Forces Chief Gen. Fabian Ver and two other military generals of plotting and killing Aquino. Agrava, however, argued that there was insufficient evidence to implicate Ver.

Since the Agrava Board was not a court of law, Marcos forwarded its findings to the Tanodbayan (ombudsman) “for final resolution through the legal system” and trial in the Sandiganbayan.

The Sandiganbayan Verdict Sum by VERA Files on Scribd

On December 2, 1985, the Sandiganbayan acquitted Ver and 24 other military men as well as a civilian (Hermilo Gosuico) from all liability in the case. The court fully embraced the military version of events, which was the same position that Marcos took shortly after Aquino was killed, and disavowed the testimony of the prosecution’s main witness, Rebecca Quijano (a passenger on Aquino’s flight and popularly known at the time as the “Crying Lady”).

This was noted in a telegram from the United States Ambassador to Manila Stephen W. Bosworth to Secretary of State George P. Shultz where he wrote that “the court merely glossed over without refuting the ‘concrete’ photographic, audio and video evidence adduced by the Agrava Board, and ignored altogether the evidence indicating a high-level conspiracy behind the assassination.”

The envoy went on to say, “As we reported in our August analysis of the Aquino trial . . . very little effort was made to disguise the orchestrated nature of the Sandiganbayan proceedings. It is clear that the real purpose of the trial was to mount a slow but relentless attack on the Agrava Board’s findings under the guise of legality and to condition the public to expect the eventual outcome.”

“It is of record that the Tanodbayan, Bernardo Fernandez, blocked efforts to introduce potentially crucial evidence which surfaced during the course of the trial,” the telegram added.

The Tanodbayan filed the case that would be known as People v. Custodio, et al.(referring to BGen. Luther Custodio, commander of the Aviation Security Command) before the Sandiganbayan. Ver and Maj. Gen. Prospero Olivas, then commander of the Philippine Constabulary Metropolitan Command, were among the eight who were indicted only as accessories.

Shortly after Marcos was deposed, the courts were urged to reopen the case. In March 1986, Deputy Tanodbayan Manuel Herrera, one of the prosecutors in Aquino’s case wrote a statement (and in June 1986 testified in court) that there had been a “failure of justice” in the criminal proceedings.

Herrera told a special Supreme Court commission (formed to determine if the Aquino case should be reopened) that on January 10, 1985, Marcos summoned him, Sandiganbayan Justice Manuel Pamaran (presiding justice), Justice Bernardo Fernandez (Tanodbayan) and other prosecutors to a meeting in Malacañang. Also present in the meeting were Justice Manuel Lazaro and then first lady Imelda. Herrera said that in the two-hour long meeting, Marcos induced them to undertake a sham trial on Aquino’s case.

In his comment dated April 14, 1986, Herrera narrated how Marcos was at some points angry and then calm and pragmatic throughout the meeting where he made it clear that although it was politically expedient to charge the defendants in court, the endgame had to be a dismissal of the case.

Herrera relayed Marcos’s sentiments, “Politically, as it will become evident that the government was serious in pursuing the case towards its logical conclusion, and thereby ease public demonstrations; on the other hand, legally, it was perceived that after (not IF) they are acquitted, double jeopardy would inure. The former President ordered then that the resolution be revised by categorizing the participation of each respondent.”

The Supreme Court G.R. 72760 further detailed Herrera’s testimony on how the men accused of conspiring to kill Aquino were acquitted. A part of it reads:

Herrera further added details on the “implementation of the script,” such as the holding of a “make-believe raffle” within 18 minutes of the filing of the Informations with the Sandiganbayan at noon of January 23, 1985, while there were no members of the media; the installation of TV monitors directly beamed to Malacanang; the installation of a “war room” occupied by the military; attempts to direct and stifle witnesses for the prosecution; the suppression of the evidence that could be given by U.S. Air Force men about the “scrambling” of Ninoy’s plane; the suppression of rebuttal witnesses and the bias and partiality of the Sandiganbayan.

By the end of the conversation, “after the script has been tacitly mapped out,” Herrera said that Marcos told the prosecutors: “Mag moro-moro na lang kayo.”

His parting words, according to Herrera, were “Thank you for coming. Thank you for your cooperation. I know how to reciprocate.”

The Commission found that “the only conclusion that may be drawn therefrom is that pressure from Malacanang had indeed been made to bear on both the court and the prosecution in the handling and disposition of the Aquino-Galman case.” This was in turn given credence by the Supreme Court, and on September 12, 1986, ordered a re-trial of the Aquino murder case.

Documents left by the Marcoses in Malacañang after they fled at the height of the 1986 People Power Revolt can give us a closer look into how Marcos’s henchmen helped create a spin for Ver and the others accused of Aquino’s murder.

Coming into the criminal proceedings in February 1985, the military defendants who, like Olivas, were caught red-handed trying to mislead the Agrava Board about the firearm that was used by the gunman.

During the hearings, Olivas forwarded the “Magnum theory,” which alleged that Galman used a Smith & Wesson .357 Magnum to shoot Aquino. The firearm was supposedly retrieved by Sgt. Arnulfo De Mesa, a member of Aquino’s supposed close-in security unit, from Galman. Olivas used as basis for his theory Chemistry Report No. C-83-872, which was an examination of fragments from a standard Magnum bullet, not the bullet fragments recovered from Aquino’s head.

The minority report found that Olivas excluded from the report he submitted on December 19, 1983 and his testimony on June 27, 1984, the second chemistry report (No. C-83-1136) which was the analysis of the two fragments from the actual bullet that killed Aquino. This document revealed that the murder weapon was either a .38 or a .45 caliber pistol, not a .357 Magnum.

The minority report said that the reason for exclusion was clear, “the first report supports his [Olivas’s] theory, but the second overthrows it.”

In response to Olivas’s misstep, Presidential Secretariat Ed Adea wrote a memorandum to Ver dated February 1, 1985 (coursed through Col. Balbino Diego) proposing a strategy for the trial of the military defendants (and one civilian) before the Sandiganbayan. On this same day, the defendants were brought before the court for the arraignment on the criminal proceedings.

Adea’s memorandum was connected to their “little talk last Saturday in the Study Room,” reffering to Marcos Sr.’s office in the presidential palace. He suggested to Ver: “We can give a break to the respondent soldiers by changing a minor aspect of the defense theory as framed by Gen. Olivas. How: By admitting the supposition that the fatal caliber .38 was fired from the .357 Magnum of Galman.” (Emphasis from the original)

He continued, “But we need a witness, preferably an expert expert (sic) on firearms, to demonstrate this.” Adea believed they could still change their position at that stage because the Sandiganbayan trial had “not yet begun.”

Cendana’s Information P… by VERA Files

The Marcos propaganda machine shifted gears nearing the release of the Sandiganbayan verdict. Three weeks before the decision came out, Malacañang was already preparing to condition the public on the acquittal. In a memorandum entitled “Information Program Re: Sandiganbayan Decision” (presumably addressed to Marcos) dated November 12, 1985, Cendaña wrote about a media plan to “prepare people’s mind for a verdict favorable to the accused; and then justify the decision, once”—not if—“it is handed down.”

The campaign was divided into two phases: the “pre-decision phase” and the “post-decision information program.” The pre-decision phase is further divided into four platforms: print media, national radio, television, and the international audience.

For print media, one plan was to publish a four-part series “only carr[y]ing the byline of the Bulletin reporter covering the Sandiganbayan.” The strategy was to emphasize the “sterling records” of the judges and to recap some of the “key characters” in the trial. The reporter was to make references to the “sordid personal life” of the Galman family’s counsel, Lupino Lazaro, and “the Quijano woman’s legal and psychiatric profile.”

The same narrative would be rehashed in a 30-minute special to be produced by the news department of the Maharlika Broadcasting System, and aired on government-controlled television networks.

Another “special-report type program is to be prepared for showing over the Pilipino station, Channel Two,” Cendaña said in the memo. For the international audience, the same program would be aired “on existing NMPC TV outlets in Chicago Los Angeles, and Honolulu, which are beamed to the Filipino communities in these U.S. cities.” The information minister even proposed “buying time in San Francisco and New York local stations” for this “special report.”

To maintain a veil of credibility, Cendaña noted that “the two programs are to be low-key, ‘objective’ in tone and non-argumentative. They will be made up mostly of clips from the Sandiganbayan proceedings.”

As for the post-decision media plan, the program starts on the day the decision was handed down. Day 1 was all about making sure that the OMA had control over the framing of the news regarding the verdict. As early as 20 days before the verdict, Cendaña said that a PNA report would be prepared “to ensure that we hit the right tone for the Pamaran statement and the reactions from General Ver and the president.” The OMA would also take charge of drafting statements for Marcos and Ver, coordinating with Pamaran about his talking points explaining the court’s decision, and shepherding how Filipino diplomats were to respond to questions from the foreign press.

Day 2 of Cendana’s plan dealt with the herding of “friendly” reactions to the decision, while Day 3 was about running “friendly analyses.” The PNA, Cendaña said, could “commission a noted criminal lawyer to write his own assessment of the case.” In this phase, the minister suggested that the OMA produce a “Where are they Now?” series “to give our side a chance to point out that the crying lady now lives in the United States with all her family—including three brothers whose applications for visas had initially been denied.”

Before he concluded the proposal, Cendana said that a separate information program was being prepared by his agency “to deal with the issue of Gen. Ver’s reinstatement as Chief of Staff.”

Within November 1985, before and after Cendana submitted his information strategy memo, Marcos publicly stated that he would reinstate Ver if he was acquitted, at one point stating that the reinstatement would be “automatic.”

But their renewed relationship as president and armed forces chief was brief. In a little over two months, these two ruthlessly powerful men and their families were fleeing the Palace from civilian crowds and defecting soldiers that they had hoodwinked far too many times.

(Larah Vinda Del Mundo is a researcher at the Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines Diliman. Miguel Paolo P. Reyes and Joel F. Ariate Jr. helped in writing this article. This piece is part of their Center’s on-going research program, the Marcos Regime Research.)