![]()

BY SENDING drug dependents to military camps, President Rodrigo Duterte may have ticked off yet another box on the list of policies that push the country backwards.

STATEMENT: In his first State of the Nation Address, Duterte ordered the Armed Forces of the Philippines to get military camps and facilities ready for drug rehabilitation. He said:

“We will also prioritize the rehabilitation of drug users. We will increase the number of residential treatment and rehabilitation facilities in all regions of the country. The Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) will facilitate the preparations for the use of military camps and facilities for drug rehabilitation.”

Source: Full text of President Rodrigo Duterte’s State of the Nation Address, July 25, 2016

BACKSTORY: At the moment, the AFP is eyeing four camps: Fort Magsaysay in Nueva Ecija, Camp Capinpin in Tanay, Rizal, and Camp Kibaritan in Bukidnon and a military facility in Cebu, according to spokesperson Brig. Gen. Restituto Padilla.

Admitting the armed forces lacked expertise, Padilla told VERA Files the rehabilitation centers will still be run by the Department of Health. This is the first time the Philippines will adopt such setup, he said.

While the primary role of the AFP is to lend existing facilities, it will also intervene, where needed, in administering physical exercises among drug dependents and “discipline (them) according to military regulations,” Padilla said.

No law clearly prohibits the use of military camps as drug rehabilitation facilities, but this move runs counter to what the rest of the world has been veering away from.

In 2012, the United Nations pressed governments to close down compulsory drug detention centers, following reports of torture of people who use drugs in custody.

The UN Joint Statement on Compulsory Drug Detention and Rehabilitation Centers reads:

“The continued existence of compulsory drug detention and rehabilitation centres, where people who are suspected of using drugs or being dependent on drugs, people who have engaged in sex work, or children who have been victims of sexual exploitation are detained without due process in the name of ‘treatment’ or ‘rehabilitation,’ is a serious concern.”

Cambodian detention centers were a prime exhibit. A study by Human Rights Watch showed that where the centers are operated by the military police, there were anecdotes of rape and sexual violence, abuses during arrest, forced labor and forced military-style drills, which included beating of drug users who suffer from mental illnesses.

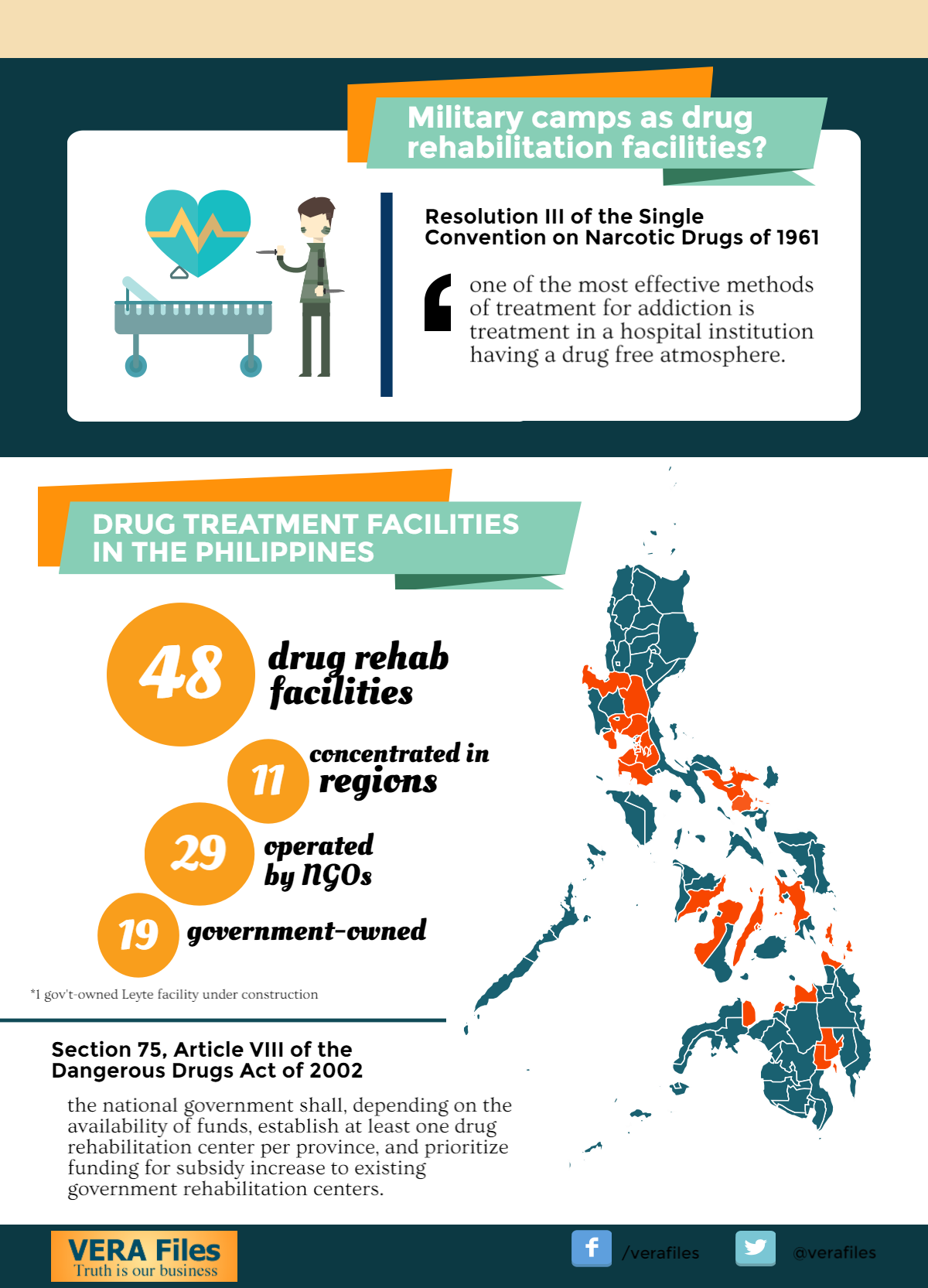

In the Philippines, there are 48 existing treatment and rehabilitation centers, 42 of which are accredited by the Department of Health, based on June 2016 data from the Dangerous Drugs Board.

A total of 29 centers are operated by non-governmental organizations, while 19 are government-owned.

The proposal to use military camps to accommodate a surplus of drug users may be a far-fetched excuse when the requirement of the law has not yet been filled.

Article VIII, Section 75 of the Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002 states that the national government shall, depending on the availability of funds, establish at least one drug rehabilitation center per province, and prioritize funding for subsidy increase to existing government rehabilitation centers. It also mandates the health department with other concerned agencies to “operate, manage and maintain” existing treatment and rehabilitation centers run by the Philippine National Police (PNP) and National Bureau of Investigation.

The facilities are concentrated in 11 regions: nine in Metro Manila and 14 in Calabarzon, where most extralegal killings have transpired since the president assumed office.

Meanwhile, Resolution III of the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of 1961, to which the Philippines is a signatory, “declares that one of the most effective methods of treatment for addiction is treatment in a hospital institution having a drug free atmosphere.”

A health-oriented approach to illicit drug dependence rather than a sanction-oriented approach is highly encouraged by the convention, the UN Office of Drugs reiterated in 2010.

Padilla said an inter-agency committee comprised of the AFP, DOH, the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency and the Philippine National Police has yet to convene to formulate protocols governing the management of rehabilitation facilities.

Sources:

UN Office of Drugs and Crime

Human Rights Watch

UN Joint Statement on Compulsory Drug Detention and Rehabilitation Centers

Dangerous Drugs Board Directory of Rehabilitation Centers (updated as of June 2016)

Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002