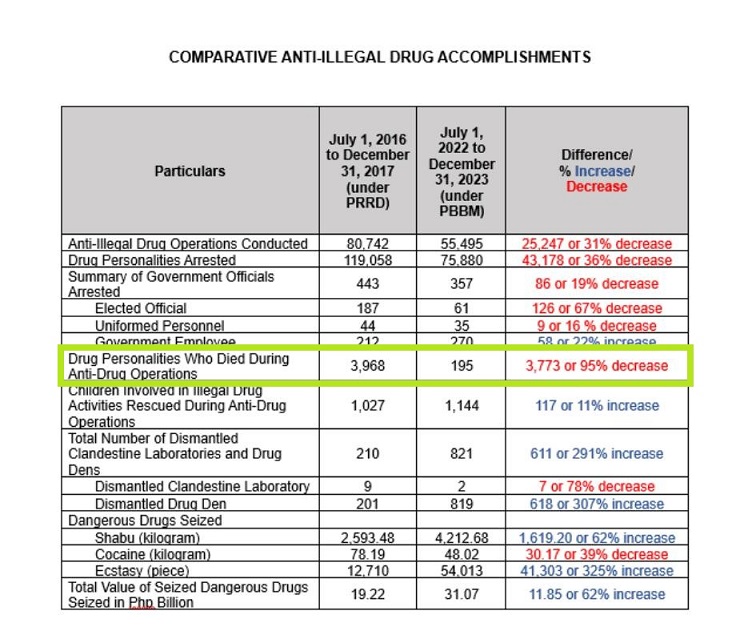

Two days after former president Rodrigo Duterte was hauled off to The Hague on March 11 to answer before the International Criminal Court (ICC) charges of crimes against humanity stemming from his bloody war on drugs, Joseph Frederick Calulut, spokesperson of the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA) claimed in an interview on state television that in its first 18 months, the Marcos administration committed 95% fewer killings in its anti-illegal drugs operations than the Duterte administration for the same period.

In PDEA’s record, 195 were killed in the first 18 months of the government of Ferdinand Marcos Jr. Nothing near Duterte’s record of 3,968 persons killed for the same period.

Yet, read against the Marcos government’s “bloodless” drug war propaganda, the PDEA figure is now part of the few instances that the Marcos government made public a partial tally of its own drug war killings.

Five months into his term, on November 14, 2022, Gen. Rodolfo Azurin Jr., then chief of the Philippine National Police (PNP), disclosed in a media forum that the Marcos government was responsible for 46 killings: “32 of the slain alleged drug offenders died during police operations, while 14 were killed by agents of the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA).” In February 2023, Azurin mentioned that in January 2023, the police killed four drug suspects.

In a June 12, 2023 Rappler story, the PNP admitted to seven “drug personalities” killed in police operations from January 2022 to April 2023, only two of which happened under Marcos’s term. Pressed to clarify its response, the PNP changed its answer and now said that seven were killed from June 2022 to April 2023. This number contradicted what then PNP Chief Azurin already shared.

Azurin’s successor, Gen. Benjamin C. Acorda Jr., in a report on his first 100 days in office (April 24–August 1, 2023) counted 73 killings in the police’s anti-illegal drug operations.

Former PDEA Director General Moro Virgilio Lazo, in a statement before the House committee on dangerous drugs on October 9, 2023, said that PDEA operations caused 19 deaths from July 2022 until September 2023.

And now, we have PDEA’s number on “drug personalities who died during anti-drug operations” from “July 1, 2022 to December 31, 2023 (under PBBM)”: 195

What is peculiar about this information is that it is year-old data. It can be traced to a March 25, 2024 post in PDEA’s Facebook page, “PDEA Top Stories.” The Philippine Star (“Drug Killings 95 Percent Lower than in Previous Admin”) and One News (“Drug Killings 95% Lower Than In Previous Administration”) both reported on PDEA’s press release, which was meant, as was obvious in its title, to signal “The New National Anti-Drug Campaign Under ‘Bagong Pilipinas’.”

And with Duterte’s arrest, the Marcos administration decided to reuse the PDEA data to once again draw contrast between the Duterte administration and itself. Calulut fumbled selling this point in his PTV interview. Joey Villarama, one of the hosts of “Bagong Pilipinas Ngayon” asked him: “Sir, sa mga operations naman po natin, paano po tinitiyak na walang nalalabag na karapatan ng mga sangkot sa illegal drugs?” Calulut replied: “Well, one of the means is the use of body-worn cameras. So, ‘yun ‘yung sa paglabag ng karapatang-pantao, ‘yan po ang primary na objective po na ginagawa ngayon ng PDEA. Kung titingnan po natin ‘yung ating datos, noong—this is comparative lang, ano po. Ilan ho ba ‘yung namatay mula, compared noon sa—ang laki ng ano, decrease, that’s 95% ho.”

ABS-CBN News, with the headline “Marcos Admin’s Anti-Narcotics Campaign ‘Human-Rights Based’,” did not bother to use this particular number from PDEA and focused instead on other matters that Calulut discussed during the brief interview. But Malaya Business Insight (“PDEA Reports 95% Decrease In Drug Killings Under Marcos Admin”), Journal News Online (“PBBM’s 1st 18 Months’ of Drug War Resulted In 95% Less Deaths”), and the Philippine Star (“PDEA: Drug-Related Killings Down 95%”) ran similar headlines of reports rehashing details of PDEA’s 2024 press release.

Only the Philippine Star report tried to put context to the PDEA numbers by citing the findings of the Dahas Project of the UP Third World Studies Center. It drew, in particular, on a news feature on the Dahas Project’s report, “Drug-Related Killings in the Marcos Administration, Year 2 (2023-2024).” “Contrary to the figures released by the PDEA, however, the University of the Philippines Third World Studies Center’s ‘Dahas Project’ recorded a 10 percent increase in drug-related killings in 2024.” This is the point that the PDEA data and the bits and pieces of information from the PNP would like to paper over: to measure the progress of the Marcos administration’s campaign against illegal drugs in relation to its own effort in the almost three years that it has been in power.

The Dahas Project started its weekly monitoring of reported drug-related killings in 2021, its findings mainly shared through its X (formerly Twitter) account, https://x.com/DahasPH. For its sources, the Dahas Project relies on online media reports and statements from the PNP and the PDEA (rarely on the AFP) on particular killings. As stated in the Dahas Project website, “an incident is drug-related if the victim was killed through violent means and meets at least one of the following criteria: killed in a drug-related operation, activity, or encounter; involved in the drug trade or in the war on drugs in whatever capacity (e.g. alleged drug personality, law enforcer, informant, etc.); in possession of illegal drugs at the time of the killing or when the body was found; associated with someone involved in the drug trade; and was killed by someone reported to be involved in the drug trade for drug-related reasons.”

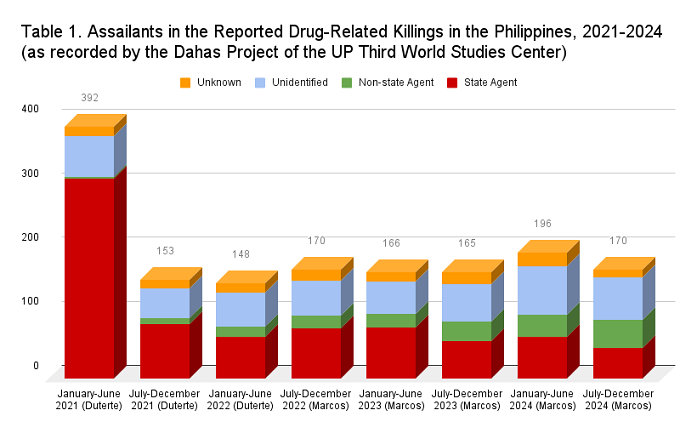

When President Marcos assumed office at noon of June 20, 2022, the murderous rampage of the Duterte years was at its tail end. In the last 18 months of the Duterte administration, when the Covid-19 pandemic raged, the Dahas Project recorded 460 killings committed by state agents (police, PDEA, and the occasional involvement of elements from the armed forces).

As mentioned, the PDEA recorded 195 “drug personalities” killed in the government’s anti-drug operations from July 2022–December 2023. In the same period the Dahas Project recorded 215 killings committed by state agents. The numbers slightly differ, but the change in administration halved the lethality of the government’s drug war.

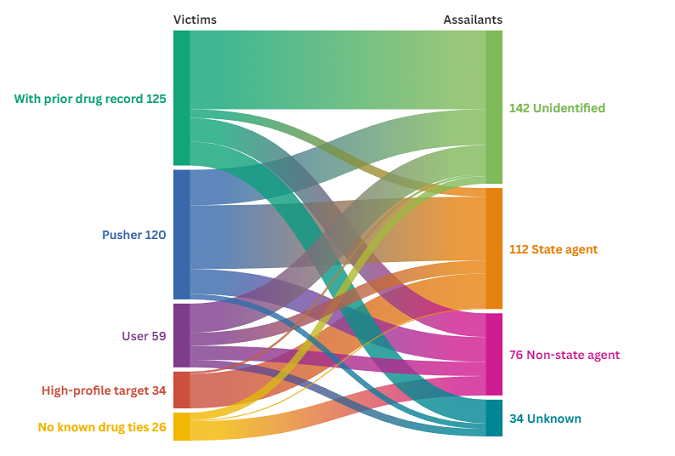

However, what might be conveniently left out by the PNP and PDEA is that it was not just the government agents who were doing the killings because of illegal drugs. In the first 18 months of the Marcos administration, the Dahas Project recorded 501 cases of reported drug-related killings. Besides the 215 killings committed by state agents, there were 73 killings by identified assassins, 162 by unidentified assailants (there were witnesses to the assault, sometimes even video recording of it, but the perpetrators were not positively identified), and 51 by unknown killers (mainly, these were cases of bodies of persons involved in the drug trade killed some place else and dumped elsewhere). In that 18-month period, killings done by the police, the PDEA, and other armed government personnel declined from 46% at the start of the Marcos government to 35% by the end of 2023. By the end of 2024 that declined further to 28%.

Yet the state’s murderousness when it comes to illegal drugs was not accompanied by an overall decline in reported drug-related killings in the country. Since Marcos took office, on average, at least one person is killed everyday because of illegal drugs. The share in the killings of known assassins and unidentified assailants grew from 44% at the start of the Marcos administration to 65% by the end of 2024.

This shift on who were doing the killings was even mirrored in the shift on where most of the killings occurred. Until March last year, Davao City was the epicenter of drug-related killings in the Philippines, where almost all of the killings were committed by the police. But when the Marcos-Duterte alliance was rent asunder and Malacañang asserted its influence in choosing the leadership of the Davao City police, drug-related killings in Davao City stopped. Cebu then displaced Davao City as the top hot spot where most of the killings were done by hired killers and unidentified assailants. The killings of small-time players in Cebu’s illegal drug industry have reached such notoriety that the gun-for-hires have now even formed gangs on their own to do contract killings for Cebu drug lords who are operating inside prisons.

With the police and the PDEA in seeming attempt to live up to Marcos’s “bloodless” drug war propaganda, hired killers and unidentified assailants now often prey on individual drug users and to settle scores with those with prior drug records. At the start of the Marcos presidency, users accounted for 6% of the fatalities, by the end of 2024, it was at 24%; those with prior drug records counted for 30% in mid-2022 and by the end of 2024 they were at 40%.

And if Marcos is indeed waging a “bloodless” drug war, how would he recognize the men and women in uniform who died in anti-illegal drugs operations?

In the Dahas Project monitor, one of the victim categories is “no known drug ties.” “This usually includes passersby or individuals associated with targeted drug suspects (e.g. kin, employees, neighbors). This category also includes cases of mistaken identity, where the victim was killed because he or she was believed to be involved, erroneously or without sufficient evidence, in the drug trade or the drug war in any capacity. They can also be law enforcers who were killed in drug-related law enforcement operations.” There were 16 state agents who were killed in the line of duty since Marcos assumed office until the end of 2024: two members of the armed forces, two PDEA agents, and 12 police officers.

The Marcos government was indeed becoming less bloody compared to the previous administration, but it was not, definitely, its incessant propaganda notwithstanding, waging a “bloodless” drug war.Or that the Marcos efforts in confronting illegal drugs was exponentially different from what Duterte did.

(Joel F. Ariate Jr. is a university researcher at the Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines Diliman. He oversees the Dahas Project. Follow the weekly and monthly numbers of the Dahas Project at https://twitter.com/DahasPH. Aidrielle Raymundo and Miguel Reyes provided research assistance for this piece.)