Sen.Leila de Lima. File photo

The foremost prisoner of conscience in the country has just been acquitted of one of three drug charges against her and moves ever closer to freedom after nearly four years of unjust detention at Camp Crame, Quezon City.

In his Inquirer column, John Nery explained the several instances that have made Senator De Lima “a martyr of Philippine politics”: “harassed in the corridors of Malacañang and the halls of Congress; demonized by fake sex-video accusations; arrested on trumped-up drug-related charges; victimized, twice, by a pusillanimous Supreme Court (the first time when it refused to protect her after prosecutors changed the case against her without conducting a new preliminary investigation, the second time when it refused to protect her in her habeas data petition against the President); abused by a justice system that stretched her cases over many years despite fatally weak evidence. And yet there she was, fighting the good fight.”

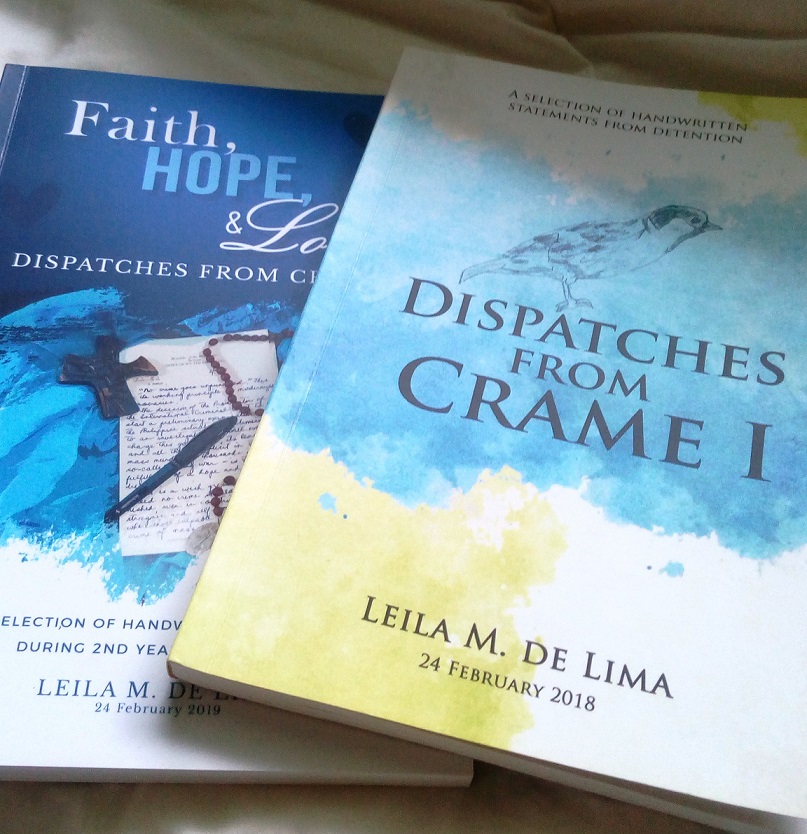

Her two books, Dispatches from Crame I and Faith, Hope & Love: Dispatches from Crame II, are damning evidence of the extent to which political persecution is carried out by the Duterte administration against its perceived enemies. They also shine a light of hope for all other political prisoners in this supposedly democratic country.

The author wrote in an early dispatch and compared him to the Red King in Alice in Wonderland, saying her persecutor is “the leader of government (who) uses public resources to avenge himself for personal slight, that is the very characteristic of a tyrant and a tyranny. Beyond fascism, this is boundless monarchial entitlement drawn from the dark ages of kings of old, of invoking the divine power of life and death over whosoever crosses the king and incurs his personal ire.”

De Lima is not visited by bouts of self-pity despite her isolation from family, friends and colleagues. But she is human enough to lament in frustration: “My fellow Filipinos, why do we allow him (Duterte) to get away with so much?”

Not only does this accused point at her accuser for subjecting Filipinos to so much “verbal abuse and pointless ramblings of a madman,” she also hits the administration for using her as “a diversionary tact…his favorite punching bag, me.” It seems all this is to cover up the regime’s failure in its war on drugs and stopping large-scale drug smuggling.

As former chair of the Commission on Human Rights and secretary of justice, De Lima sees with her practical and legal eyes that the Duterte move for absolute power involves the removal of an independent Ombudsman and Chief Justice and their replacement with lapdogs or what she calls “the most depraved grovelers.”

As she elaborated, “This is a time when men and women of integrity and independence are persecuted, while con-artists, shysters and frauds are honored and glorified.”

Her voice, her books are bold testimony against the 13,000 bodies piled up during the drug war. The books are touchstones that tell the world, particularly the United Nations and the International Criminal Court, not to forget.

She noted how “under Duterte’s watch, the country’s international reputation has gone from high to zilch” no thanks to his son being linked to high-stakes shabu smuggling, his family owning billions of pesos of hidden wealth, his relinquishing of the South China Sea/West Philippine Sea to China, his offering virtual amnesty to the country’s top plunderers and so on.

Like the little boy and truth teller in the fairy tale “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” De Lima pointed out that Duterte is no “strong man” but “a damaged man.” Then she proceeded to explain why the leader acts like a raving madman: “poor judgment, loss of empathy, socially inappropriate behavior, intensified vulgarity, lack of inhibition, inability to concentrate on the real issues.”

Repeatedly, she declared her innocence. “I’m not a drug trafficker. I’m not a narco-politician or a drug coddler.” And the country’s top citizens have taken heed of this. The endorsement of her books reads like a virtual who’s who in public service, human rights advocacy, journalism, social criticism.

Dr. Sylvia Estrada Claudio, in her foreword, commends De Lima’s first volume as “good prison literature” that “humanizes the detainee…In Senator De Lima’s dispatches, you will see not only the public servant and the human rights defender, but also the particular woman. Her trials are laid bare—her despair for a nation that has not risen in moral indignation, her heartbreaks for her children, her longing for her old life, her favorite stray cat, her delight at seeing old friends, her missing her father who taught her the principles of truth, justice, integrity.”

But most of all, the books reflect, in Joe America’s words, “the passions of a person who genuinely cares about the Philippines and Filipinos.”