Photo from the Department of Agriculture – National Tobacco Administration, taken by Kristin Mae S. Castañeda.

When the COVID-19 pandemic struck, agricultural workers like 67-year-old Rita Soriano of Balaoan, La Union province had to grapple with disruptions in farm operations.

The pandemic left small-scale farmers like her hanging by a thread to secure adequate funds for their farms, sustain the country’s agricultural production, and deal with financial shocks that affected their livelihood. Two of her fellow farmers contracted COVID-19 last year.

Yet, with morale low, and their belts tightened even more, Soriano said they could not keep planting food crops. They had to depend on tobacco — an agricultural product they should have abandoned long ago according to the law — to earn their keep.

Soriano had been planting tobacco since she was a teenager and, despite it being labor intensive, said she doesn’t see leaving tobacco farming anytime soon because it is “more lucrative” and has a ready market for them, unlike other crops.

“Kung kami lang ma’am, habang nabubuhay kami, ‘di namin iiwan yung tobacco kasi ‘yan lang tabako ang pagkakakitaan mo nang mas marami (For us, as long as we’re alive, we will not abandon tobacco [farming] because that’s our main source of livelihood),” she said.

Planting sandiya (local watermelon) and corn would yield an income of only P20,000, said Soriano. “Kung maganda ang panahon, mas maganda ang tobacco (If the weather’s good, planting tobacco is better),” she added.

But decades after laws were passed to advance the self-reliance of tobacco farmers and help them shift to production of agricultural products other than tobacco, they remain at the mercy of private companies and traders who keep them planting through cash loans and dictate the value of their produce which are mostly for export. Small-scale farmers continue to suffer despite the laws that are supposed to help and protect them.

——————————

Laws to assist tobacco farmers

Republic Act 9211 – The Tobacco Regulation Act of 2003

· Section 33 mandates the government to provide a tobacco growers’ assistance program to tobacco farmers displaced by the implementation of this law or who have voluntarily ceased to produce tobacco.

· It also mandates the creation of a tobacco growers’ cooperative to assist farmers grow other crops, develop alternative farming systems, among others.

Republic Act 7171 – An Act to Promote the Development of the Farmer in the Virginia Tobacco Producing Provinces

· Specifies that 15 percent of the proceeds from excise taxes on locally manufactured Virginia type of cigarettes be allotted to provinces producing them.

——————————

Soriano’s story is symptomatic of the decades-old dependence on the industry of local tobacco-growing households.

According to a 2016 study on the economics of tobacco farming led by the Action for Economic Reforms, the relationship between farmers and the tobacco industry has been “consistently lopsided” in favor of the latter.

In a survey involving 421 tobacco farmers from 33 tobacco-growing municipalities in the Philippines, the AER study found out that the average annual income of households surveyed was P158,408 — 70 percent of which came from tobacco farming, while the rest came from planting other crops.

But the study noted that there is no value of labor included in this calculation, as majority of the respondents were “contract farmers,” or those with a production and/or marketing contract with a tobacco firm.

“Tobacco farming is widely considered the most labor-intensive crop, often 10 or more times as labor-intensive as other commonly-cultivated crops. Assigning the lowest estimated value to this labor, farmers’ profits drop precipitously, or for a large percentage, evaporate all together,” it noted.

Dr. Ulysses Dorotheo, executive director of the Southeast Asian Tobacco Control Alliance, said that tobacco farmers continue to be “at the losing end” of the industry that traps them in “a cycle of debt” with a “reassuring market for them.”

Soriano herself says natural disasters and the health crisis forced them to take a loan of around P250,000 to plant tobacco on three hectares of land, only to earn one fifth of what they had to spend.

The National Tobacco Administration (NTA), an attached agency of the Department of Agriculture, said that they ensure tobacco farmers’ products will be bought — that not a single leaf would be wasted under its tobacco contract growing system.

However, Dorotheo said farmers “have no way to complain if they think the quality of their produce is good but the leaf grader said otherwise,” so they would be forced to sell them at a lower price. (Leaf graders determine the quality of tobacco leaves based on a close examination of their physical attributes, age, location on the plant, and the type of soil the plant was sown in, among others.)

Every two years, the NTA, tobacco farmers’ groups and tobacco manufacturing companies would meet in a tripartite conference to evaluate and negotiate the floor prices of unprocessed tobacco leaves.

The latest agreement approved in 2020 set the floor prices per kilogram of Virginia top grades at P84 for Grade AA and P83 for Grade A. Burley top grades A and B are priced at P72 and P69 per kilo, respectively, while high grade of the native type is P73 per kilogram.

However, the AER study noted that “many farmers reported that buyers treated them unfairly in terms of classifying, grading and pricing, and that they lost money as a result.”

Food security

Dorotheo said this economic disadvantage could have been prevented if the potential of growing other high value crops, such as rice, corn and other food crops, had been fully realized, which he said could bring more income to farmers and contribute to the country’s food security.

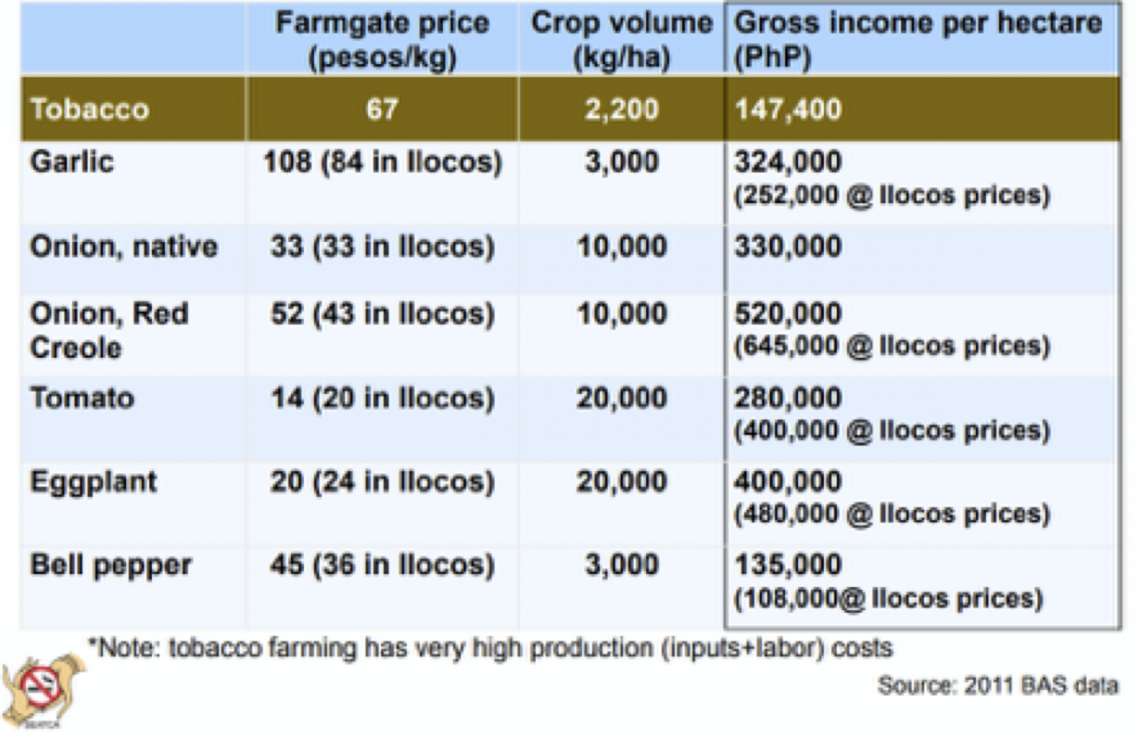

This table from SEATCA shows how much more farmers could have produced and earned in planting high-yield crops rather than tobacco should they have gotten more support.

As early as 2008, the SEATCA has noted that tobacco cultivation utilizes significant portions of agricultural land in Southeast Asia that might otherwise have been used for much-needed rice or other food crops.

The reason for this, according to SEATCA, was because both farmers and national governments see revenues from tobacco cultivation as more advantageous than other food crops at the outset, but the table above proves that other crops are just as profitable.

“But while tobacco cultivation may seem profitable, growing rice or corn appears to have higher yields and profit. Tobacco farmers, however, perceive that they have greater profits from tobacco produce because their gross income is higher,” said SEATCA in its paper that looked at the cycle of poverty in tobacco farming.

“During the time of COVID-19, people need food. I have no idea why they are still promoting tobacco when people need food and are going hungry,” said Dorotheo. He also cites the lack of proper nutrition, especially among children.

“We’re putting our country at risk, particularly our young people,” said Dorotheo.

A recent study by the United Nations on the impact of COVID-19 on food systems in Metro Manila highlighted the need to ensure reliable and functioning food supply in times of crisis and natural disaster.

Among the key findings in this research is how COVID-19 caused severe disruptions to food markets and systems that directly affected workers in the agri-food and fisheries sector affecting “the vulnerable, as small-scale food producers are considered less resilient to COVID-19 shocks.”

Dorotheo stresses that “the urgency here is that … our country needs food. Our farmers live on a day-to-day existence — if they don’t plant, they don’t eat basically. It is ironic and is an injustice that those who feed us are the ones who grow hungry.”

Vested interests

In theory, the excise taxes collected by the government from locally manufactured Virginia, Burley, and native tobacco products, as outlined in Republic Acts 7171 and 8240, could have addressed these gaps.

These laws seek to address the supply side of tobacco by combining tobacco control measures with livelihood assistance, as stakeholders encourage Filipino farmers to shift from tobacco, promote their own cooperatives, and encourage agricultural research and development.

The Sin Tax Reform Law, passed in 2012, mandates the government to earmark 15 percent of incremental revenues from tobacco excise taxes for provinces producing burley and native tobacco to “assist tobacco farmers in planting alternative crops or implementing other livelihood projects.”

However, the AER said in their study that this approach “requires careful scrutiny of what drives the market for tobacco as well as the incentives that make farmers” stay with tobacco cultivation.

“Studies point to the low returns of tobacco farming and the unequal trading relations in which farmers are caught. There is general willingness to shift to other, notably high-value crops, but credit, market and related value chain constraints pose challenges, limiting the reach of nascent successes,” the AER survey noted.

Soriano’s town, Balaoan, is the top producer of Virginia tobacco in La Union province, receiving P516.8 million or almost a third of the province’s P1.7 billion share from the government’s tobacco excise tax collections in 2017.

In November 2020, the Department of Budget and Management said the tax collection reached P18 billion, to be divided among beneficiary tobacco-growing provinces.

Dorotheo said that local governments, with billions of shares from excise tax collections, have a huge role to play to uplift farmers’ lives.

But why has it been difficult for them to realize the laws’ objectives and, at the same time, promote comprehensive tobacco control programs?

“Obviously, there are vested interests between the tobacco industry and landowners, plus the landowners and the politicians who are receiving the tax revenues,” said Dorotheo.

For NTA administrator Robert Victor Seares Jr., a former local chief executive himself, excise taxes help fill the gaps in local funding especially in municipalities with low internal revenue allotment.

Seares ended his third mayoral term in the tobacco-growing town of Dolores, Abra province in 2019 before inheriting the position of NTA administrator from his father, Dr. Robert Seares Sr., who died in March 2020.

“Our town is a fifth-class municipality, so our internal revenue allotment is very limited. [The excise tax fund] is a form of additional funding for our farmers… so I used that to improve their lives,” said Seares, noting that he distributed farm equipment, like tractors, as well as seedlings, and livestock to Abra farmers. “That money is theirs,” he continues.

Role of LGUs

Under the law, LGU shares from tobacco excise tax collections should be used for cooperative, livelihood, agro-industrial, and infrastructure projects.

However, a review of available LGU reports on excise tax fund utilization showed that the biggest chunk of tobacco funds are being used on infrastructure.

Shares of LGUs in tobacco funds had also been historically misused or misappropriated for politicians’ pet projects that do not benefit farmers, according to government reports.

A 2009 Newsbreak report exposed how the provincial government of Ilocos Sur constructed a P332-million tomato processing plant that had remained unused for years, using the tobacco funds that were supposed to improve tobacco farmers’ lives.

In May 2017, Congress investigated the alleged misuse of tobacco excise tax funds in the province of Ilocos Norte from 2010 to 2016 under former governor and now senator Imee Marcos. Republic Act 7171 mandates that 15 percent of tobacco excise taxes be allotted for projects that support tobacco farmers, but Marcos allegedly used P66.45 million worth of tobacco funds to instead purchase 40 mini cabs for barangays in the province, five second-hand buses, and 70 mini trucks for municipalities.

The Commission on Audit found in 2009 that local officials in Ilocos Sur had “misused, misappropriated, or failed to account for at least P1.3 billion” of the province’s tobacco fund. The Office of the Ombudsman then filed in 2013 graft charges against former Ilocos Sur governors Luis “Chavit” Singson and Deogracias Victor Savellano for tobacco fund misuse.

And while the law mandates transparency over the use of the fund, some provinces had failed to submit the quarterly fund utilization and program reports pursuant to RA 7171 and RA 8240.

Only La Union had so far uploaded on its website a report of how funds from RA 7171 had been utilized by the province for the first quarter of 2021.

With all of these happening, tobacco farmers, however, continue to be at the backdrop of the industry controlled by major players in the industry.

Seares said the NTA maintains “close communication” with private companies in the industry so they could “work together for the betterment of our tobacco farmers.”

“We are mandated by law to help the farmers and to help the tobacco sector. So [I tell the private sector], don’t think of us as enemies. We are not enemies. We could help fill each other’s gaps because we work hand in hand in this industry,” he said.

Dorotheo said tobacco farming takes up only half a percent of the country’s agricultural labor force, so promoting other crops would still be economically viable.

During off season for tobacco planting, Seares said it would support around 42,000 farmer-beneficiaries through alternative livelihood programs, such as raising beef cattle and planting rice.

But he said: “We cannot deny the fact that the tobacco industry is a big industry that helps the government increase its revenue, with 85 percent of excise tax collections alloted to universal health care.”

Tobacco control, however, is also part of the mandate of local government units, as the country aims to reduce and, ultimately, eliminate smoking.

“While now there are many LGUs involved in tobacco control in a strong way and there are others who are concerned, [some of them] do not know what to do or do not have information about the tobacco industry,” said Dorotheo.

At the end, it would be a difficult balancing act for local governments: where tobacco-growing provinces would have to provide comprehensive programs that will promote the lives of farmers and LGUs elsewhere would have to take a more proactive approach in tobacco control.

This story is produced under the Nagbabagang Kuwento (Burning Stories) Tobacco Control Media Program of the Probe Media Foundation Inc. supported by the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids.