The lighted candles symbolize the nine long years of waiting for justice for the 58 killed in the Maguindanao massacre. Photo by Meeko Camba.

At last Friday’s remembrance of the Maguindanao massacre at the Bantayog ng mga Bayani, the feeling was a mixture of frustration and hope.

Frustration because it has been nine long years and the families of the 58 victims- 32 of them members of media – have still to see conviction for the massacre, one the darkest marks in ourhistory of struggle for a democratic society.

Hope because government officials said the decision on the case is expected in early 2019. Given the overwhelming evidence against the identified perpetrators led by former Datu Unsay Mayor Andal Ampatuan Jr, the families of the victims, lawyers, supporters and government officials are expecting a conviction.

A conviction would indeed be a substantial part of the justice the families and those who value human lives seek.Hopefully, that would make a dent to the culture of impunity that emboldened Ampatuan and his cohorts to waylay the convoy of Genalyn Mangudadatu who was on their way to file the certificate of candidacy of her husband, Buluan Vice Mayor Esmael “Toto” Mangudadatu, for governor of Maguindanao against Andal Jr. for the 2010 elections, brought them to a grassy hill off the road, and shot all of them one by one.

An eyewitness said Andal’s white shirt turned red with the splattered blood of the victims but he continued shooting without emotions. Then he tried to bury the dead using a backhoe that was used for construction of government road projects.

There is feeling of concern among journalists, however, that even with a conviction of the Maguindanao massacre murderers, the culture of impunity – a person’s belief that he is exempted from punishment for something that has been done that is wrong or illegal- remains among people in authority or of influence .

This is noted by the Committee for the Protection of Journalists in its 2018 Global Impunity Index released last month which ranked the Philippines fifth among states with the worst records of prosecuting the killers of journalists, next to Somalia, Syria, Iraq and South Sudan.

An improvement actually because in 2016, the Philippines was number four.

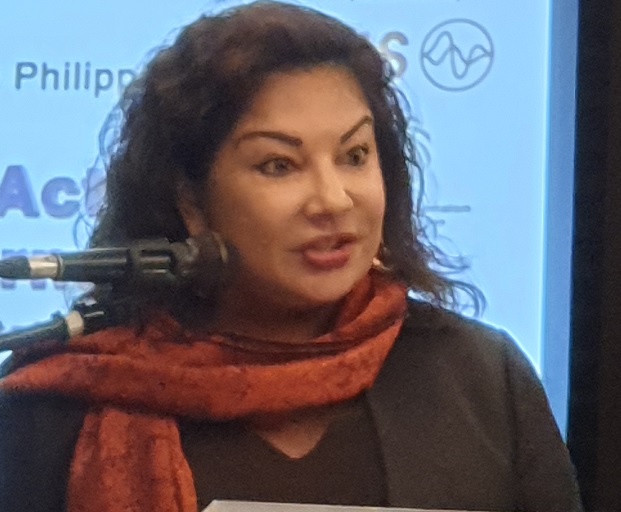

Lila Ramos Shahani, secretary-general of the

Philippine National Commission for The United Nations Educational, Scientific

and Cultural Organization, put it in an enlightened context during her speech

at the consultation for the crafting of the Philippine Plan for Action on

journalist safety organized by the Asian Institute of Journalism Communication

early this month.

Assistant Secretary Lila Shahani

Shahani said: “Revisiting this year’s CPJ ratings reveals that we are substantially different from the four countries considered more dangerous than the Philippines. For over a decade, Somalia has intermittently been without an effective government, while Syria’s government has seen the country become the sight of a complex proxy war leading to a flood of refugees all over the world.

“As of Iraq, many of our younger journalists may not even remember a time when that country was not engaged in a war or set of insurgencies. And finally, South Sudan is one of the world’s newest countries and has been strife –torn throughout its struggles against genocide and for autonomy and independence – continuing on through rebellion and civil war.

“These four countries, subject to armed conflict and with governments defending themselves in civil war, are understandably dangerous places for journalists to work.

“But what about the Philippines? What makes journalism such a dangerous profession in a country like ours, with our long history of relatively stable, if not always democratic – governance, facing a few comparatively minor attempts at sustained insurrection? Is it not impunity itself, as our justice system remains perpetually clogged with pending cases? Indeed, impunity arguably remains the greatest challenge in fighting for a free and pluralist media landscape in the Philippines.”

Shahani took note of the contribution of the Maguindanao also known as the Ampatuan massacre to our notoriety: “The Ampatuan massacre, of course, is what propelled us to the top charts, and continues to keep us there. Today more than 100 of the accused actors and conspirators remain on trial – nine full years come the 23rd of this month – after the killings in Maguindanao took place.

“But the massacre, as black a spot on the record as it is, cannot be allowed to blot out the numerous unprosecuted or unresolved cases of violence against individual journalists. Tragically, by 2015, the number of individual journalists subsequently killed surpassed the total deaths from the 203 Maguindanao massacre itself (note: according to data by the Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility). Additionally many journalists (including photojournalists) also claim to have suffered severe psycho-social trauma from the government’s recent war on drugs. Impunity endangers us all, but perhaps together, we all can seek, find and implement effective solutions to improve journalist safety.”

This requires a separate column.