Mischief Reef – lost under Ramos presidency

Scarborough Shoal – lost under Benigno Aquino III presidency

Spratlys including Sandy Cay-surrendered to China under Duterte presidency

Foreign SecretaryAlan Peter Cayetano

Foreign Secretary Alan Peter Cayetano was being smart the other day when he challenged critics of the Duterte’s complacent attitude in the face of China aggressive moves in South China Sea.

At the flag-raising ceremony at the Department of Foreign Affairs, he said: “I challenge anyone of them, whatever their profession – justice, politician, newsman, journalist – if we lost a single island during Duterte’s time, I will pack my bags, go home.”

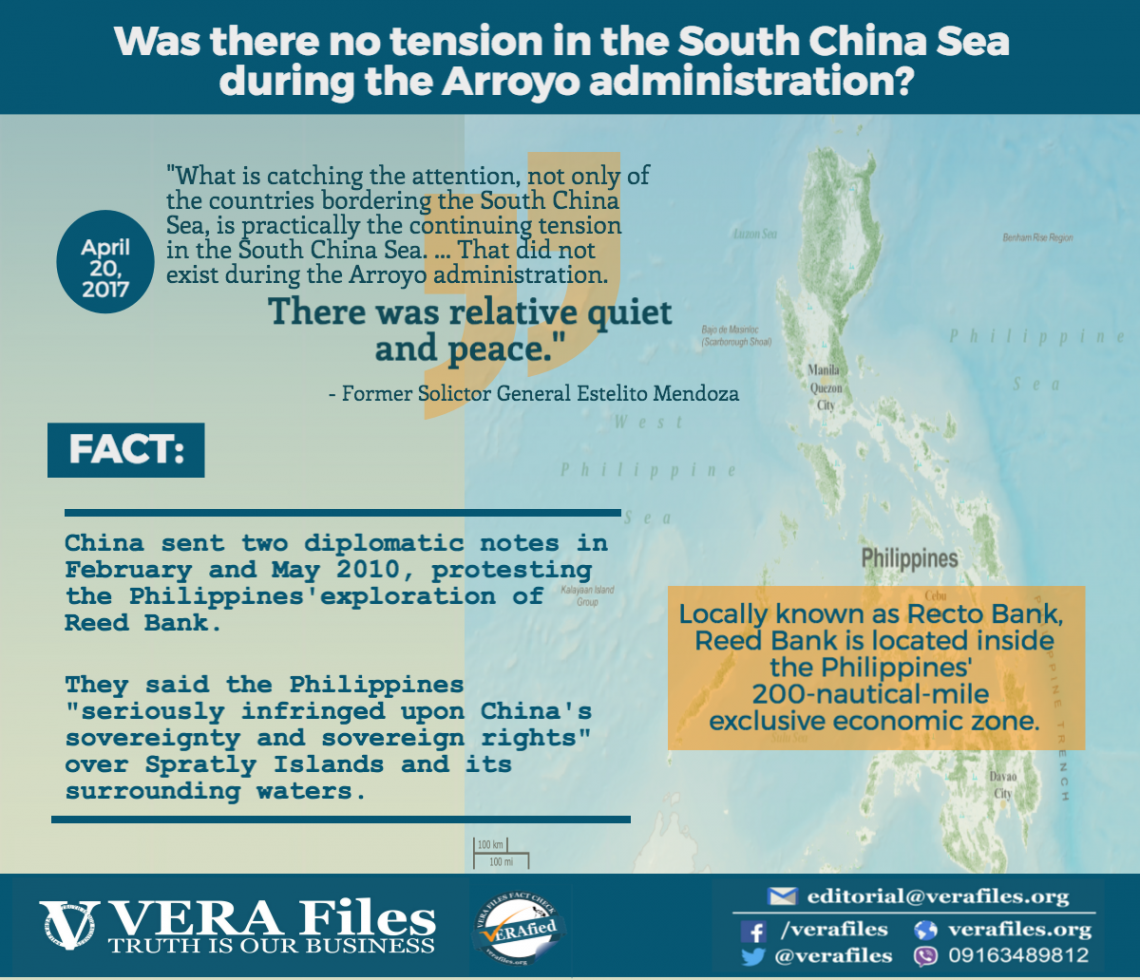

It is a smart strategy because if we go deep into the history of the South China Sea conflict, we will be reminded that it was during the term of President Fidel V. Ramos that we lost Mischief Reef (Philippine name: Panganiban Reef) in 1995 and Scarborough Shoal under President Benigno Aquino’s watch in 2012.

Others may argue that we have not lost Scarborough Shoal. But the fact that Filipinos, government personnel and fishermen can only go there with the permission of Chinese Coast Guard whose ships (at least two) are permanently guarding the shoal means that we have lost control over that feature 124 nautical miles from the shores of Zambales.

In the July 2016 decision of the Arbitral Tribunal in the case filed by the Philippines against China, it was noted that the shoal also known by its Philippine name as Panatag and Bajo de Masinloc is a traditional fishing ground of Filipino, Chinese, Vietnamese fishermen and it should remain so.

That had always been the situation before April 10, 2012. Chinese fishermen caught in Philippine waters is not an unusual happening – be it in Scarborough shoal in the northwestern side of the country or in the Spratlys, in the southwestern part of the country. When that happens, the fishermen are charged in court and the Chinese Embassy works for their release. The case is usually handled in the provincial and regional level.

Chinese Coast Guard Surveillance ship guarding Scarborough Shoal.

The situation changed on April 10, 2012 when, in violation of the “white to white, gray to gray.” rules of engagement in a sea conflict (“White to white” means civilian ships are to deal only with civilian vessels. “Gray to gray” means navy to navy.), the Philippine warship BRP Gregorio del Pilar arrested eight Chinese boats with sizable quantities of endangered marine species, corals, live sharks and giant clams.

China claims Scarborough Shoal as part of its all-encompassing nine-dash line map of the South China Sea. Diplomats andsecurity experts believe that the Chinese have been eyeing control of Scarborough Shoal, just 650 kilometers from the nearest major China’s land mass, the southern island province of Hainan. They were just waiting for an opportunity as their naval capability grew.

They saw that opportunity onApril 10, 2012 provoked by the bungling of Aquino and his Foreign Secretary Albert del Rosario. The standoff (which saw some 90 Chinese vessels against three Philippine ships) lasted two months with the three Chinese ships remaining in Scarborough up to now.

Aquino and Del Rosario tried to recover Scarborough Shoal and other disputed features in South China Sea, including Mischief Reef, by filing the case before the Arbitral Court, which thePhilippines largely won.

China responded to its loss in the Arbitral Court by engaging in massive reclamations and creating artificial islands on the rocks and reefs they occupied in the disputed area.

Mischief Reef. Photo from AMTI.

Mischief Reef, according to the surveillance photos by the US-based Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, has become a garrison complete with an airport.

Chinese occupation of Mischief Reef was exactly not unprovoked.

A 1998 study by then Lieutenant Michael Studeman of the U.S. Navy showed that the Chinese occupied Mischief in retaliation to what it considered “betrayal” by the Philippines.

Studeman wrote:

” China’s occupation of Mischief Reef was not a bolt from the blue; it was preceded by a chain of events that began with a falling-out with the Philippines over hydrocarbon exploration in the northeast region of the Spratlys.

“Joint development talks between China and the Philippines over gas-rich Reed Bank broke down in early 1994; in May, Manila decided to grant a six-month oil exploration permit to Alcorn Petroleum and Minerals.27 The Philippines was interested in collecting seismic data on the seabed southwest of Reed Bank. Manila hoped the contract would remain a secret, but news of the collaboration soon leaked. Beijing swiftly issued a statement reasserting its sovereignty over the area covered by the license and ignored Manila’s belated invitation to become a partner in the project. Manila back-pedaled on the diplomatic front for weeks, but the damage had been done. By secretly licensing an exploration effort the Philippines had appeared to engage in unilateral efforts to exploit the natural resources of the Spratlys.

“Stung by Manila’s ‘betrayal,’ China decided to advance eastward for better surveillance coverage of any Philippine-sponsored oil exploration. Mischief Reef is in the lower-middle section of the Alcorn concession; a presence there would also strengthen China’s hand were petroleum ever to be discovered in the area. The Chinese post on Mischief Reef was discovered by Filipino fishermen in February 1995, the advanced state of its buildings indicating that construction had begun in the fall of 1994, just a few months after Manila’s ‘faux pas.’ China had quietly advanced onto the reef because it believed physical occupation was the only method by which Chinese interests could be protected. Beijing’s own misstep was in not foreseeing that this characteristically ‘defensive’ response would be interpreted as offensive.”

The Ramos government vehemently protested the occupation of Mischief which led to the adoption of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations the Declaration of the Code of Conduct in the South China Sea which is now being transformed into a Code of Conduct.

Fiery Cross Reef. Photo from AMTI.

Is Cayetano correct in saying that under Duterte the Philippines has not lost an island to China?

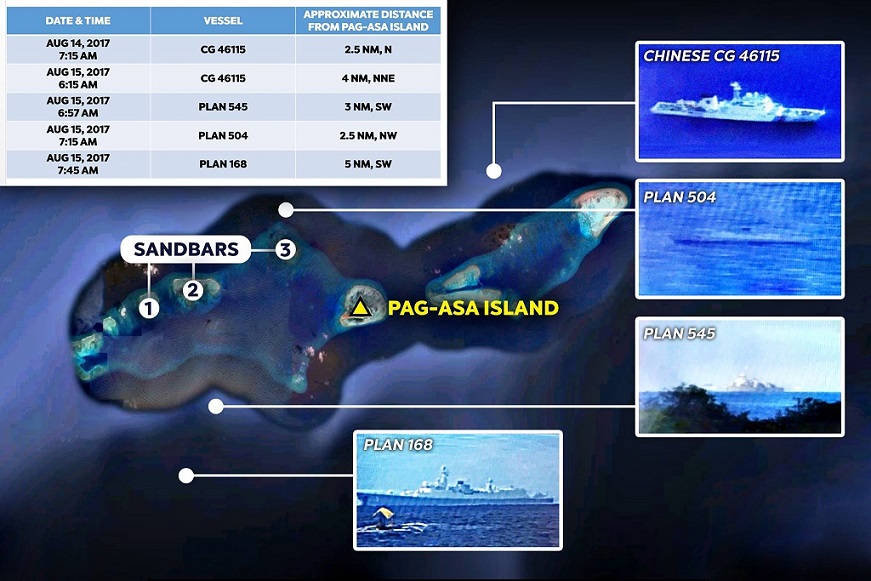

Rep. Gary Alejano (Magdalo partylist) said Cayetano should be reminded that China seized Sandy Cay, part of the Pag-Asa Island network of sand bars and reefs has been inaccessible to Philippine government vessels patrol since August last year.

“ Chinese coast guard vessels and militia fishing boats are stationed near Sandy Cay 24 hours a day, effectively seizing physical control of Sandy Cay,” Alejano said.

Last April, the People’s Liberation Army Daily announced the unveiling of a marker in its occupied Fiery Cross reef (Kagitingan Reef) as a message about China’s”determination to protect its territory and maritime rights.”

Chinese Ministry of Defense spokesperson Ren Guoqiang said “It is the natural right of a sovereign state for China to station troops and deploy necessary territory defense facilities on the relevant islands and reefs of the Nansha Islands (Spratlys).”

Malacanang and the DFA did not release any statement protesting China’s move in Fiery Cross and Sandy Cay

Acting Chief Justice Antonio T. Carpio lamenting the Duterte administration’s tolerance of China’s continued militarization ofislands the Philippines also claim in the Spratlys, warned that “Under international law, acquiescence is the inaction of a state in the face of threat to its rights under circumstances calling for objection to the threat to its rights. Acquiescence means the Philippines will lose forever its EEZ in the West Philippine Sea to China.”

By not doing anything, the Duterte administration is losing not just “a single island” but the whole of the Philippine claim in the South China Sea.

Sandy Cay. Photo by AMTI.