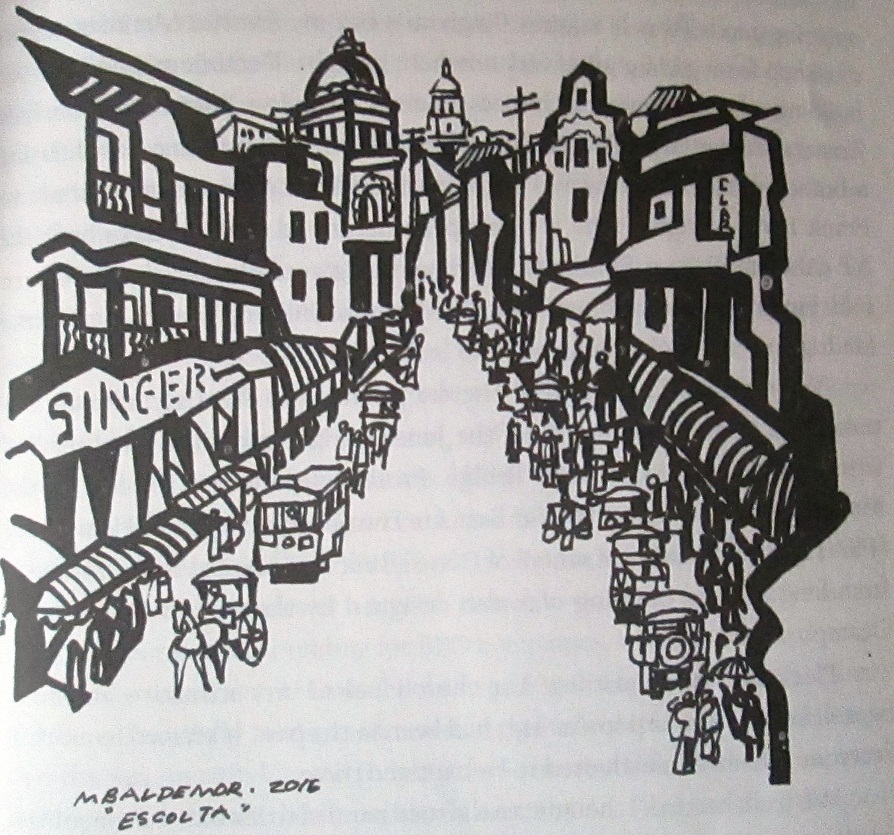

The old Escolta rendered in pen and ink by Manuel D. Baldemor

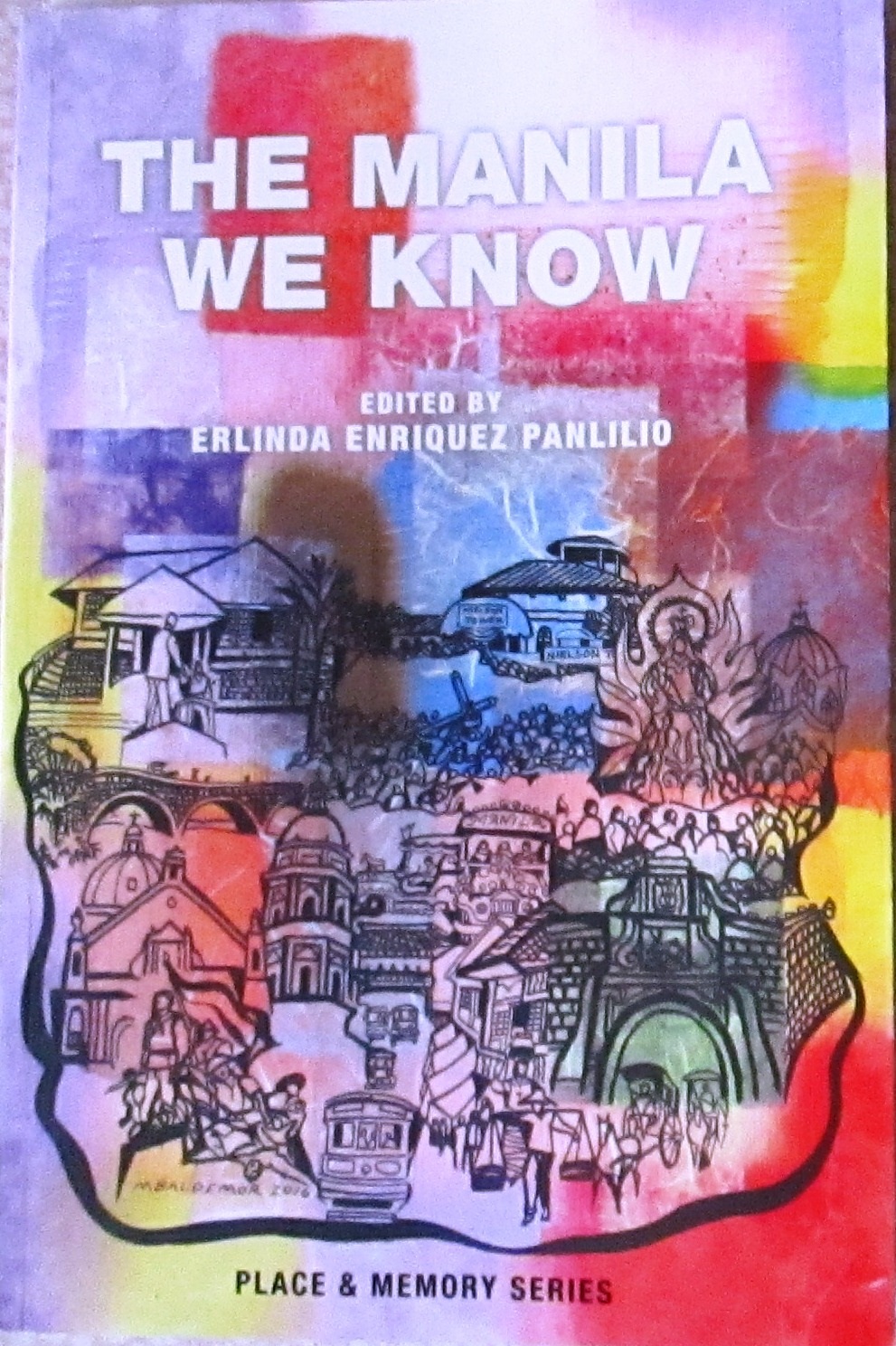

“Everything was much simpler in the olden days…” These words by Gaby Gloria describe her grandmother’s Antipolo. They also reflect the theme that holds together the 14 essays in the new anthology The Manila We Know, published by Anvil as part of its place and memory series.

Edited by Erlinda Enriquez Panlilio with charming black and white illustrations by Manuel D. Baldemor in the inside pages, the book is a literal expansion of the earlier volume The Manila We Knew (2006).

Other titles in the series are: The Baguio We Know, The Cebu We Know, The Davao We Know, The Dumaguete We Know, The Naga We Know. Soon to be launched in a Manila venue is The Bohol We Love. One has to hand it to the journalists, historians and literary writers for giving readers a magical mystery tour to some of the country’s major cities and provinces.

Not only are Escolta, Quiapo, Sampaloc and Intramuros included in The Manila We Know. The peripheral cities around and beyond the distinguished and ever loyal city make their appearances, too: San Juan, Quezon City, specifically Project 4 and Broadway, Makati, Malabon, Marikina and Antipolo, or Greater Manila, in short.

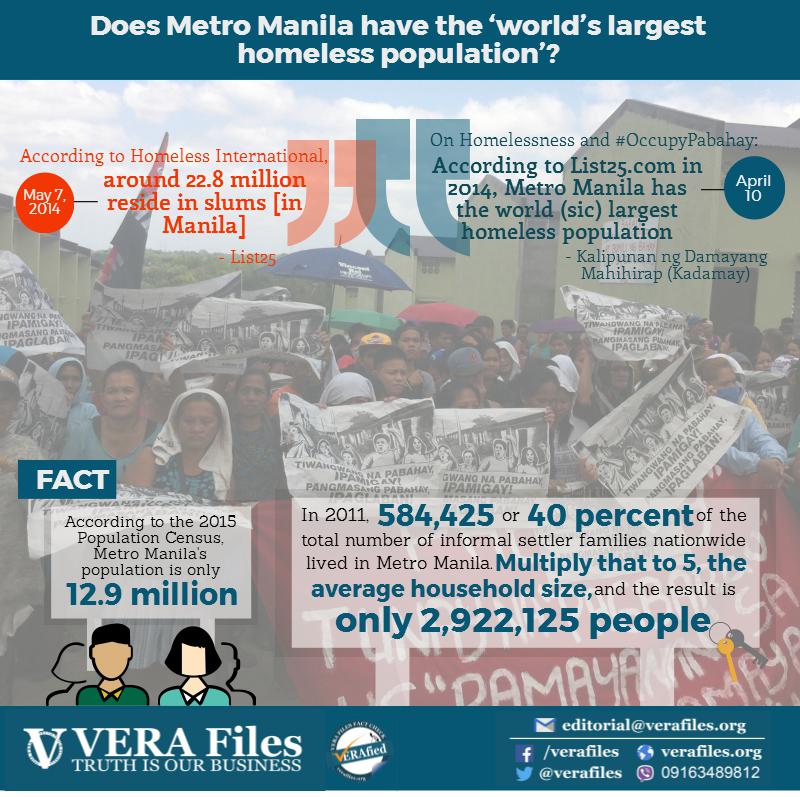

The 2015 Census puts the population of Manila and the 16 cities that make up Metro Manila at 12.8 million.

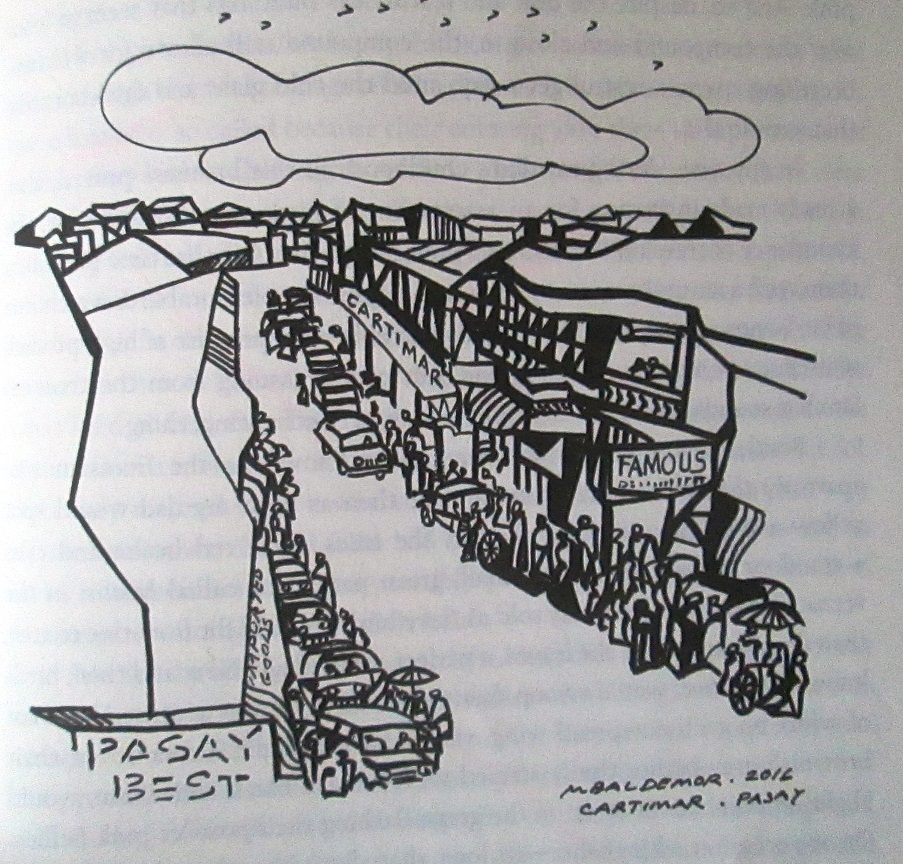

Cartimar, a shopping center associated with Pasay City

With a size like that, no wonder the writers pine for neighbors who knew and helped one another, for springs and sparkling brooks now replaced by “foul-smelling open sewage canal” (Josefina P. Manahan writing of Addition Hills, San Juan), for “enormous piedra china blocks…from the Puerta Real bridges” that former Intramuros Administration head Jaime Laya suspects are now “decorating someone’s San Juan garden,” for the fireflies in Benito Legarda’s childhood that could be captured and kept in hankies, then taken to light up darkened rooms with “a soft glow,” for a merienda of pan Americano or pan de sal freshly bought from Quiapo’s Bakerite Bakery and dunked in cups of foamy, thick hot chocolate made from scratch from tableas of cocoa balls.

The pining and nostalgia for lost ancestral homes punctuates Gloria Ocampo Reyes’s “The Quiapo I Used to Know…and Love,” Paulo Alcazaren’s “Jeproks: My Life in the Projects,” Cristina Pantoja Hidalgo’s “Elegy to My Lost Home,” Milette T. Ocampo’s “Swan Song for Broadway,” Rhoda Lopa Macasaet’s “Pasay: A View from Roberts Street,” Vergel O. Santos’s “Memories of a Tropical Spring.”

The overall tone is bittersweet and rueful. Macasaet notes the lost sound of chirruping crickets in evenings after rainfall. “All these creatures collateral damage, in the end, of the inexorable march of progress and its attendant consequences—the inevitable tampering with the environment, the overcrowding, the twin plagues of pollution and noise.”

Her essay can be retitled into a line she has written: “When the dragonflies quietly stole away.” She once lived in a house with an unobstructed view of Manila Bay until highrises and ungainly billboards mushroomed.

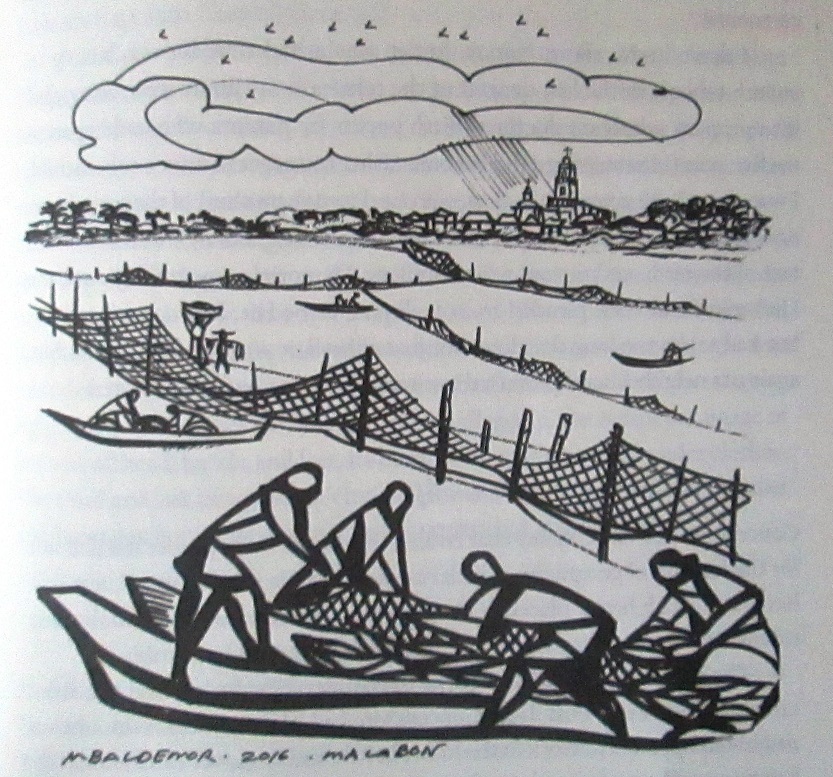

The Malabon of Santos was bucolic in his Huck Finn youth. He recalled “clamming and crabbing at low tide and line fishing anytime anywhere.” Mudfish were fair game for his father who would shoot them while Santos retrieved the fish, “an exciting enough task for which I was yet rewarded—with a shot of my own. Father never missed. Three hits, his minimum for an outing, were more than enough for a family meal.”

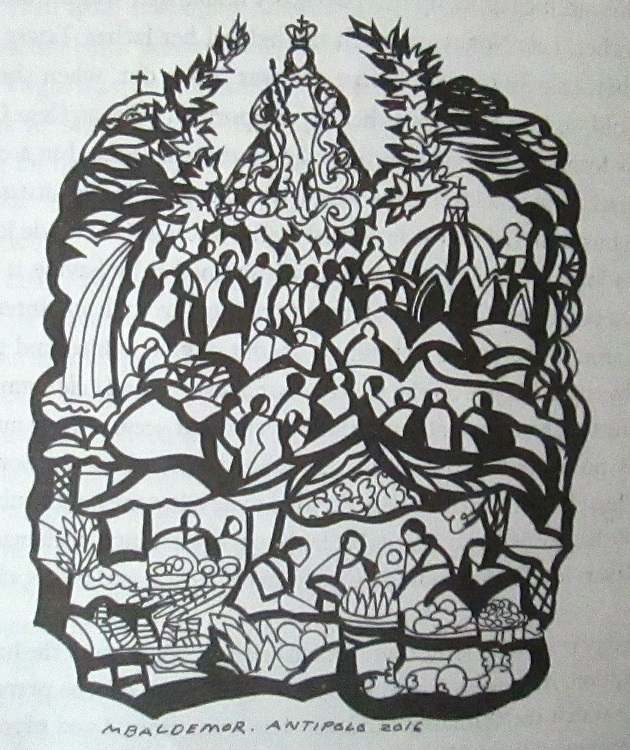

Our Lady of Peace and Good Voyage dominates this illustration of Antipolo.

Sarah F. Lumba was right in her “My Marikina” when she wrote that “it is the tongue that holds the memories that endure the most.” Marikeños are reputed to prepare their even most elaborate dishes like morcon, mechado, even buko salad and sweet garbanzos from scratch. They are famed for two particular dishes, one called Everlasting (“essentially embutido in a llanera”), and Waknatoy, a menudo with pickles.

Krip Yuson’s entry, “A Personal San Juan (as an Adopted Hometown),” is different from the rest because this kid from Sampaloc, Manila, had felt “bereft and orphaned whenever subsequent city company did some downtime on nostalgia. Only a few of us couldn’t name a hometown that commanded allegiance.”

In the early ’60s, he grew into a stalwart istambay and drinking buddy of many a lad or young adult from San Juan who later rose to prominence like the movie stud George Estregan (brother of Joseph Estrada), Chuckie, Dodong and George Arellano, the Parels of Little Baguio.

Yuson’s tale is a mix of drunken moments, shooting the breeze and misdemeanors (not paying for their tapa’t sinangag one evening when his group was intoxicated, then playing a cat and mouse game with the police and irate cab drivers).

Architect Alcazaren wrote, “We can never go back to our fishing villages or the Projects of old. Our project now is to evolve an urbanity that hopefully will provide adequate settings for our communal lives, settings free from risk and calamity, settings that will provide good memories to share with our children and generations to come.”

Fisherfolk hauling in their catch in Malabon of old