Photo by Maria Feona Imperial

By MARIA FEONA IMPERIAL

AS the deafening roar of thousands of anti-Marcos supporters reverberated around Luneta Friday night, two young people engaged in a friendly debate on the sidelines.

“Are we discounting the truth in numbers that have been published so far?” asked Ochie*, a 20-year-old aeronautics student, whose family had been a victim of land-grabbing during martial law.

The question was for Mace*, 27, a Marcos supporter who carried a placard that read: “Respect the law.”

“Truth is always with the law…are we here to question the wisdom of the Supreme Court?” Mace asked.

“As for me, I can,” Ochie said, to which Mace answered: “On what grounds?”

Ochie’s reply: “Morality. Not everything that is legal is moral.”

It’s an issue that hounds many, including legal luminaries in the country, following the Supreme Court ruling allowing the burial of the late strongman Ferdinand Marcos at the Libingan ng mga Bayani (LNMB). The High Court ruled on Nov. 8 that President Rodrigo Duterte acted within the bounds of law when he ordered the burial.

Massive protests erupted following the sudden burial on Nov. 18. Exactly a week after, on “Black Friday,” an estimated crowd of 15,000, mostly composed of young people, gathered at the Rizal Park to condemn historical revisionism and the return of the Marcos family to political power.

Some 30 supporters of Marcos and Duterte, also showed up in a counter-rally. Dubbing themselves “Duterte Youth,” they believe Marcos was worthy of a hero’s burial.

Mace, who hails from Zamboanga, was on their side. For him, Marcos had enough reason to impose martial law to “defend a land that was in chaos.”

“Marcos was a Medal of Valor awardee. He was once a soldier and a president. That enough renders good ground to give him a privilege to be interred at the LNMB,” he said.

But Ochie, who had heard from his mother firsthand accounts of abuses by the military, begged to differ.

For him, Marcos lacked “command responsibility” for allowing such abuses to happen and “moral responsibility” for failing to apologize.

“I didn’t want to educate the (Duterte Youth). I gave them my side so they could ponder on it,” he said.

Their exchange went on as the night deepened, and ended civilly when they shook hands.

Ochie then rejoined the anti-Marcos crowd chanting “Marcos, Hitler, Diktador, Tuta!” — the same battle cry in 1986, but this time, by the millennials, who are often accused of being naive and politically indifferent.

[metaslider id=48977]

Marcos vs millennials

Even martial law survivor Bonifacio Ilagan of the Campaign Against the Return of Marcoses to Malacanang (CARMMA) was awed by the turnout of the youth despite the steady downpour.

“Nag-rarally kami madalas, the same faces. But this time, mga bagong mukha talaga (We’re seeing new faces joining us),” he said.

“We encourage them to write their own placards. Makikta mo hindi generic, iba iba. Naglalabasan yung kanilang creativity at sentimyento (Their messages vary. Their creativity and sentiments are expressed),” Ilagan added.

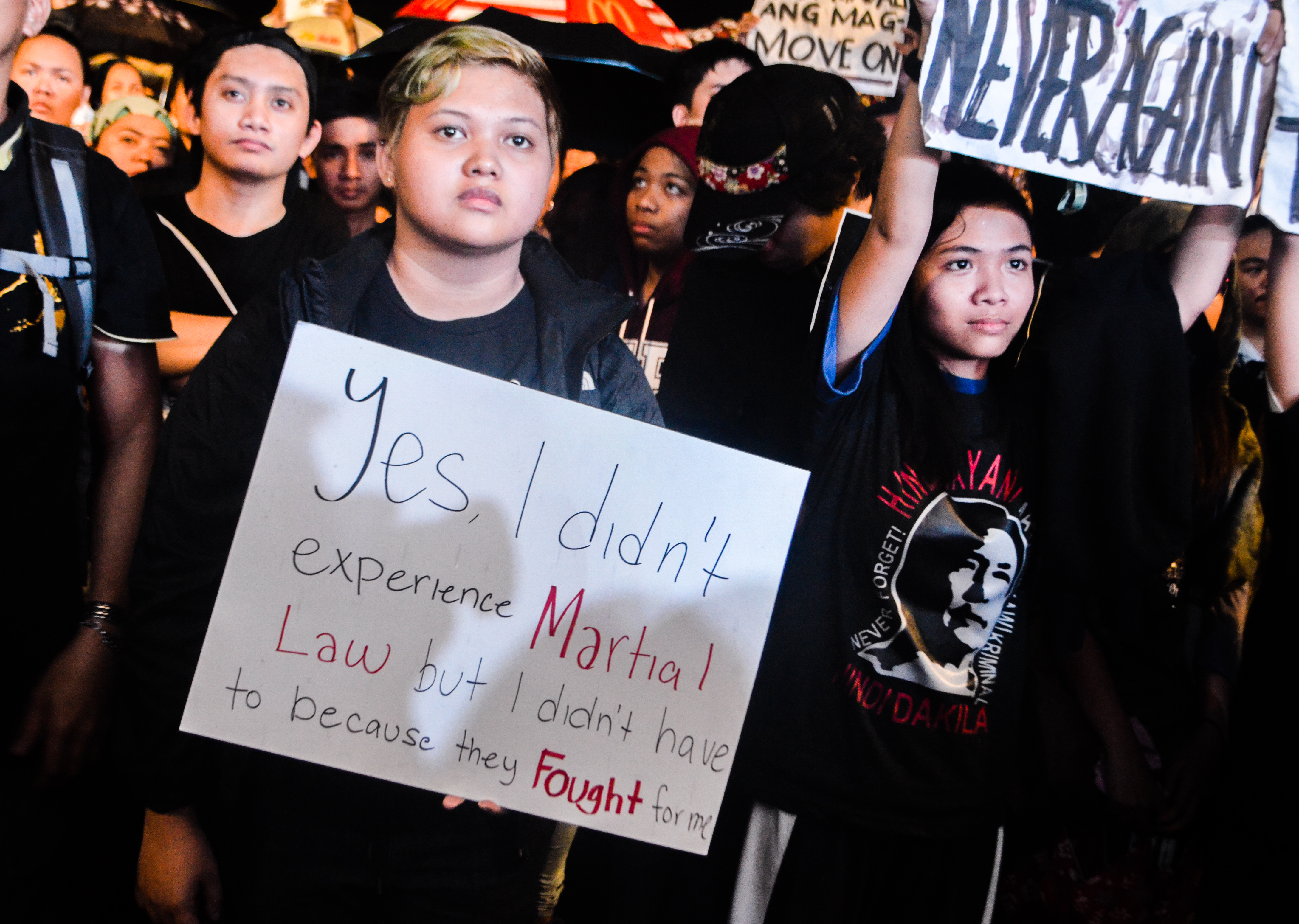

The placards conveyed a common theme: They may not have been born during martial law, but they have a full grasp of what it was like.

Among these signs were: “Never too young to #NeverForget,” and “What I learned from my history class doesn’t end on a sheet of paper.”

A more striking version was: “Yes, I didn’t experience Martial Law but I didn’t have to because they fought for me.”

One man proudly raised the sign, “Let’s make baka, don’t be takot!” a play on the signature chant, “Makibaka, huwag matakot (Fight, don’t be afraid).” Others even brought plastic shovels to signify that they want Marcos’ remains exhumed from his grave.

All these while the soundtrack of Japanese animated series Voltes Five, which Marcos banned for its alleged subversive theme, kept playing on the background.

Protest against Duterte

The protesters also directed their attacks on Duterte for granting Marcos’ last wish. A cartoon of the president’s face on a puppy’s body was waved among the crowd. A few meters away was a sign that read, “Duterte, tuta ni Marcos.”

For Ilagan, the sneaky burial implies a resurrection of a “Marcosian ideology,” or the belief that what the country needs is a strong one-man rule, where the ruler cannot be questioned nor doubted.

Ilagan offered an unsolicited advice to the president: “Iwasan na niya ang pag-threaten ng suspension of writ, o declaration of martial law (He should not threaten to suspend the writ of habeas corpus or declare martial law).”

He also doesn’t believe that the president, as the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, wasn’t made aware of the hasty burial: “Please give us a better script,” Ilagan said.

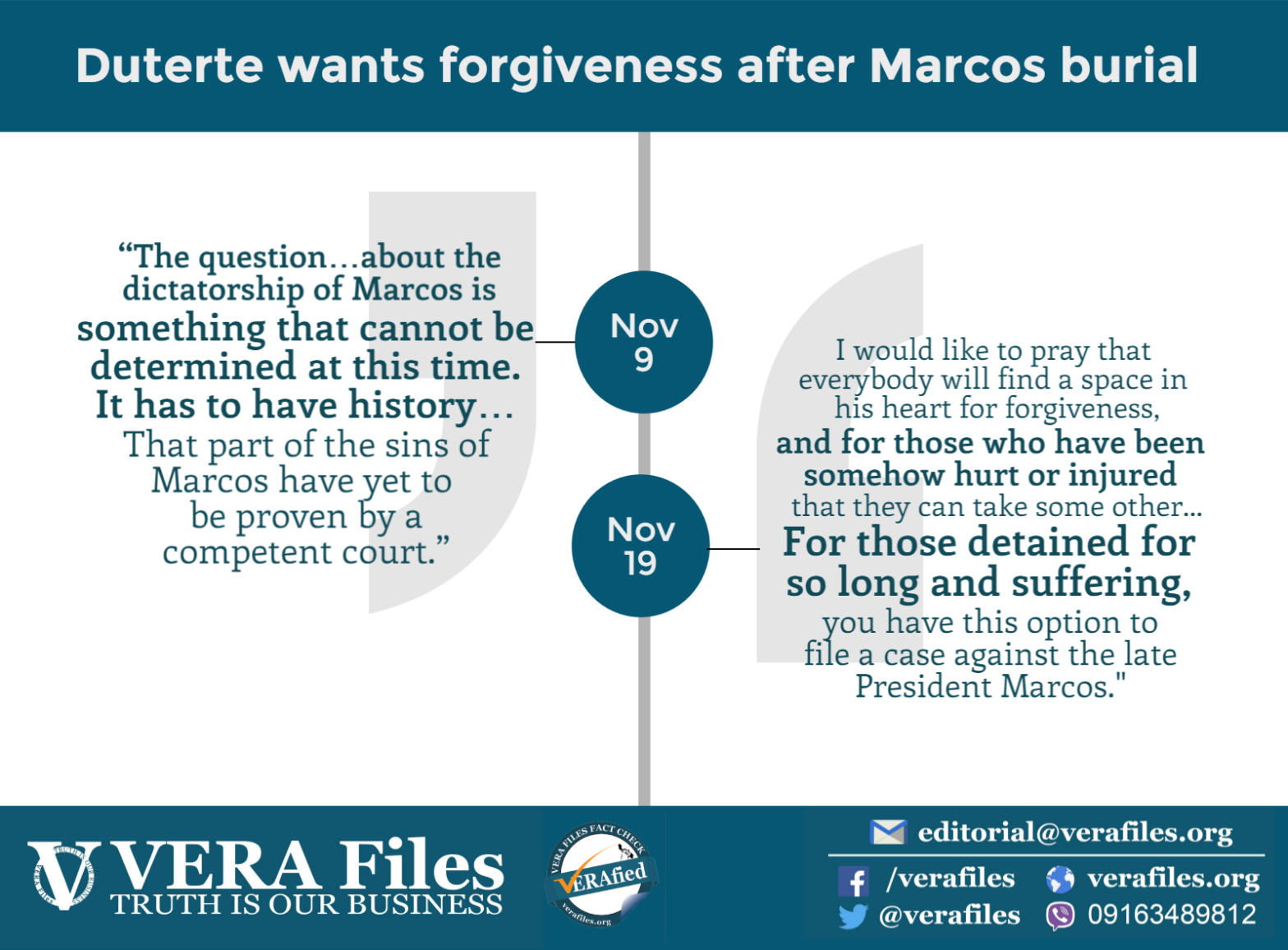

On several occasions, Duterte have downplayed the ills of martial law.

Shortly after the SC ruling, Duterte said Marcos’ sins “have yet to be proven by a competent court.” (See https://verafiles.org/vera-files-fact-check-marcos-sins-not-yet-proven-in-court/)

Later, he denied the existence of films and studies documenting martial law. (See https://verafiles.org/vera-files-fact-check-were-there-really-no-movies-about-the-martial-law-years/)

(*Both requested for their real names to be kept confidential)