IT COULD have been the year a Marcos scion almost got elected the second highest official of the land. Instead, 2016 proved it had more in store for the family of the late strongman Ferdinand Marcos Sr.

In May, Marcos son and namesake Ferdinand “Bongbong” Jr. narrowly lost the vice presidency to Leni Robredo, by a margin of a little more than 250,000 votes. (See story: Congress sets proclamation of Duterte and Robredo)

Then, in November, the remains of the former dictator were transferred at the Libingan ng mga Bayani (LNMB) in a clandestine burial, despite staunch objections, by among others no less than the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP), which said the Marcos military record was “fraught with myths, factual inconsistencies, and lies.” (See study: Why Ferdinand E. Marcos should not be buried at the Libingan ng mga Bayani)

In a single stroke, almost three decades of legal and political tussles between the Marcoses and the state ended, and the former emerged victorious.

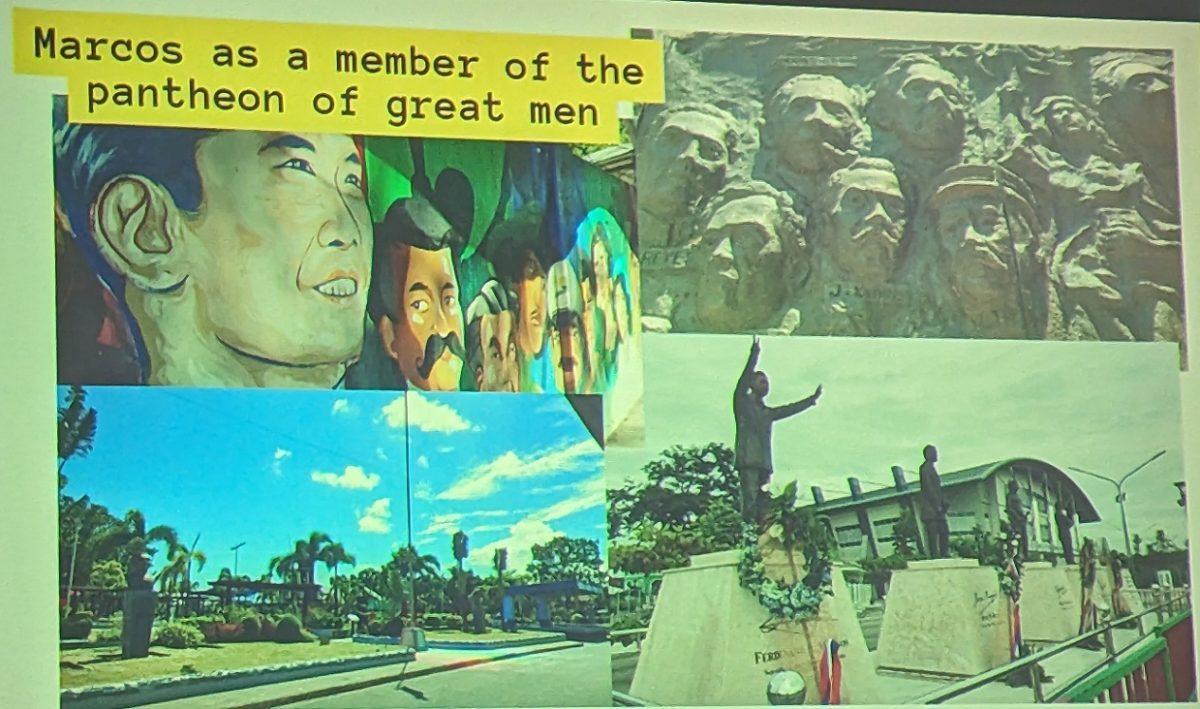

More important, such burial in a cemetery for heroes represent the further perpetuation of the myth about the heroism of Marcos that had already been debunked, and debunked many times, only to be revived as if hard historical facts did not matter at all.

A three-part series, published by VERA Files in July, has documented in-depth how the myth of Marcos as a war hero, a leader of an anti-Japanese guerrilla unit during the Second World War, is both “fraudulent” and “was a malicious criminal act.”

- See Part 1: File No. 60: Marcos’ invented heroism

- See Part 2: File No. 60: A family affair

- See Part 3: File No. 60: Debunking the Marcos war myth

The series, written by Joel Ariate and Miguel Paolo Reyes, researchers at the University of the Philippines Diliman Third World Studies Center, begin thus:

The U.S. National Archives in Washington, D.C. is home to the Philippine Archives Collection, a treasure trove of 1,401 files of the Guerrilla Unit Recognition series documenting anti-Japanese resistance in World War II.

Within that collection is File No. 60, which documents Ferdinand E. Marcos’s claim of being a guerilla leader and founder of a guerilla unit called “Ang Manga Maharlika” with thousands of men in its roster from 1942 to 1945 in Northern Luzon. Marcos himself later changed it to “Ang Mga Maharlika.”

Included in the file’s more than 400 pages are the findings made by the U.S. Army which, after repeated investigations, repudiated Marcos’ claim and called it a lie.

Capt. Elbert R. Curtis, who handled Marcos’s claim for recognition for the most part of July 1947 to March 1948, came to two conclusions.

One, that “Ang Mga Maharlika Unit under the alleged command of Ferdinand Marcos is fraudulent.” Two, that “inserting his name on a roster other than the United States Armed Forces in the Philippines, Northern Luzon (USAFIP, NL) roster was a malicious criminal act.”

From File No. 60 and a range of other historical sources, what emerges is a portrait of Marcos as one who did not let facts get in the way of audacious self-interest.

After being denied recognition and, more notably compensation, by a US Army team which investigated his supposed guerrilla unit, Marcos “tried to rebut the findings of the investigators point by point. His arguments ran for nine pages of single-spaced typescript with sixteen appendices.”

Unconvinced, the US Army “stood by its previous findings and that its decision was final and not subject to any further appeal.”

But as the series would later point out:

Not someone to stand down at the first sign of rejection, Marcos made another claim. In the 1960s, according to Primitivo Mijares in his book ‘The Conjugal Dictatorship of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos,’ when he was already a senator, Marcos tucked in in “an omnibus bill which would have granted the Philippines additional war payments to the tune of $78 million…a personal claim…for $8 million to compensate for food and war material he allegedly supplied the American guerillas in Mindanao during the Japanese Occupation of the Philippines.” In 1962, the US Congress rejected the bill.

“It was between 1963 and 1965 that the myth of Marcos the war hero was brought to new heights,” the series notes. Marcos, in a ceremony in December 1963, “received an additional 10 medals—all from the Armed Forces of the Philippines—for his alleged guerrilla exploits.”

Beyond its own debunking of the myth of Marcos the hero, the series also notes that there had not been a shortage of similar accounts before it.

Even without the damning evidence from File No. 60, Mijares in his book as well as the alternative publication WE Forum in 1982, were able to identify the inconsistencies and impossibilities in the accounts of heroism perpetuated by Marcos.

In 1983, the Washington Post published the results of an 18-month investigation which did not find “any independent, outside corroboration…to buttress a claim made in the Philippine government brochures that he (i.e. Marcos) was recommended for the U.S. Medal of Honor because of his bravery on Bataan.”

Despite all these, the series ends on a gloomy note:

All these notwithstanding, this is what is written in the Department of National Defense’s profile of Marcos: “During the outbreak of the Second World War, Marcos joined the military, fought in Bataan and later joined the guerilla forces. He was a major when the war ended.”

The very same profile, word for word, can be read at the University of the Philippines ROTC’s website.

“The rule in history,” the NHCP noted in its opposition to the Marcos LNMB burial, “is that when a claim is disproven—such as Mr. Marcos’s claims about his medals, rank, and guerrilla unit—it is simply dismissed.”

Yet, it would seem what have been dismissed in the case of the disproven heroism of Marcos are historical facts themselves.

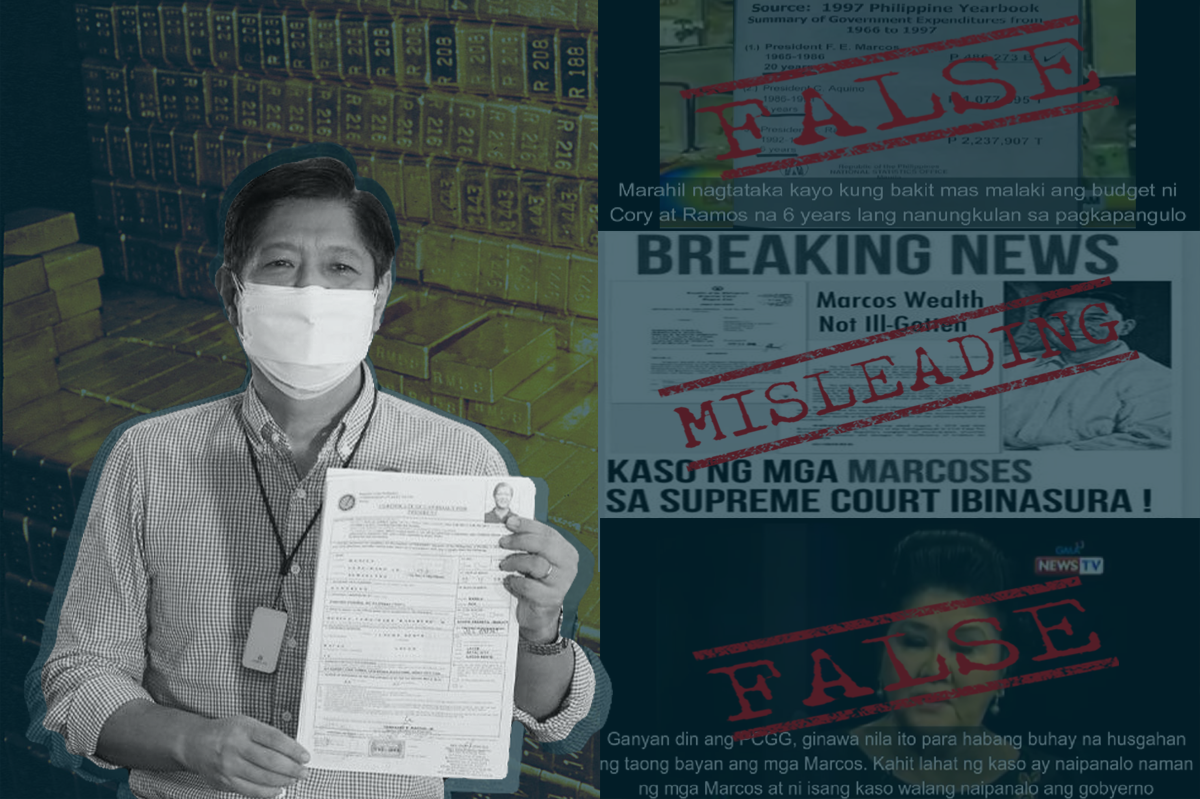

The same disregard for facts continue to animate the discussions surrounding the recent burial of the late dictator at the LNMB.

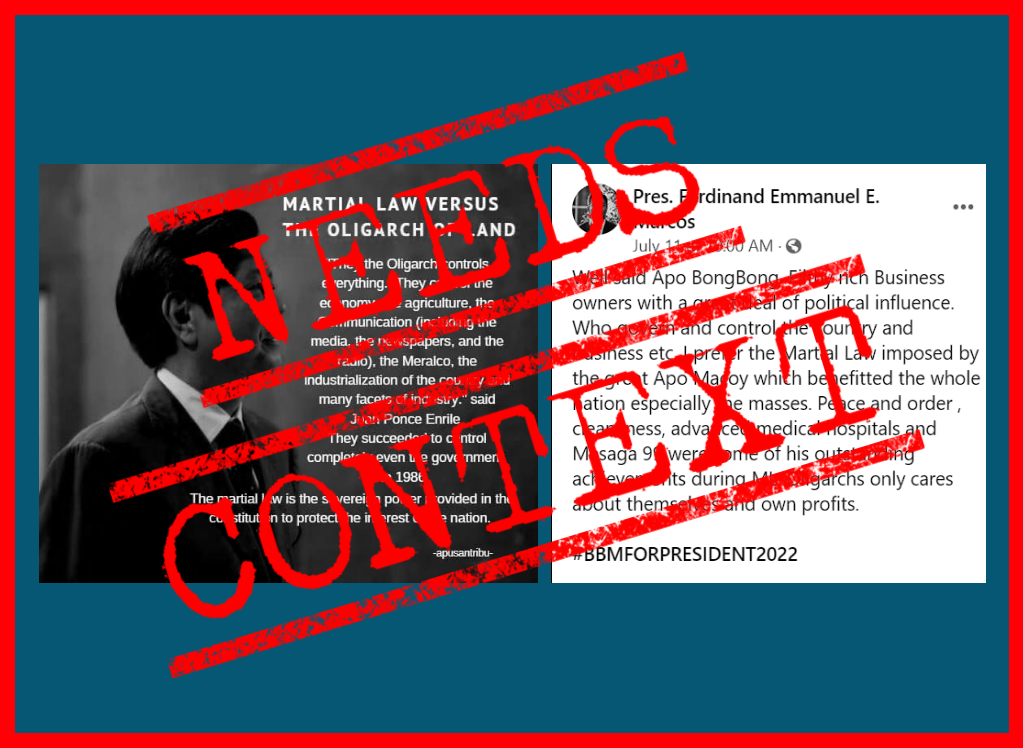

Supporters of the family of the late dictator believe that allegations against the Marcoses are nothing but lies.

One supporter has said, “Mga batang nagsisigaw na kalaban namin, na mga dilawan, walang alam. Ang binasa nilang libro hindi mo alam kung laman (kung) puro kasinungalingan (Those young people who are against us, they belong to the yellow camp; they’ve read books full of lies).” (See video: Salamat Apo – Marcos supporters celebrate at the LNMB)

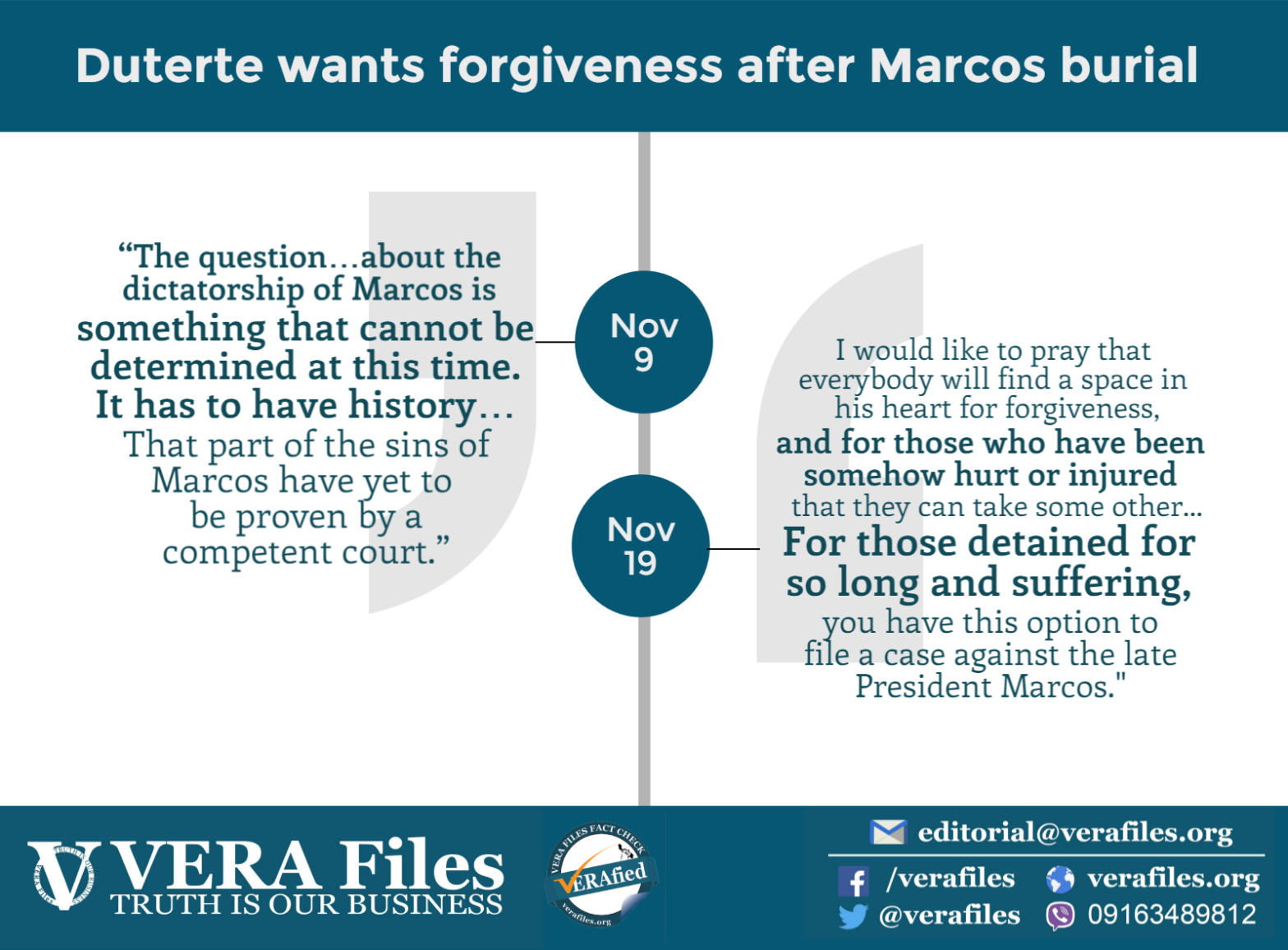

President Rodrigo Duterte himself has taken liberties with facts about Marcos. The president has claimed, for one, that the sins of the late strongman “have yet to be proven by a competent court.” This is not true. (See VERA Files Fact Check: Marcos’ sins not yet proven in court?)

In response to the outrage following the surprise LNMB burial, Duterte said “there is no movie” about Marcos and the martial law years. This is also not true. (See VERA Files Fact Check: Were there really no movies about the martial law years?)

To be sure, the LNMB burial had some tinge of legality: it was the Supreme Court itself, albeit in a controversial decision, which allowed it. More, it fulfills a campaign promise by Duterte, who won in a landslide.

Yet, instead of the national reconciliation foretold by its supporters, the LNMB burial reopened old wounds, and led to more national division. (See story: Marcos burial: A day of celebration and outrage)