First of three parts

THE U.S. National Archives in Washington, D.C. is home to the Philippine Archives Collection, a treasure trove of 1,401 files of the Guerrilla Unit Recognition series documenting anti-Japanese resistance in World War II.

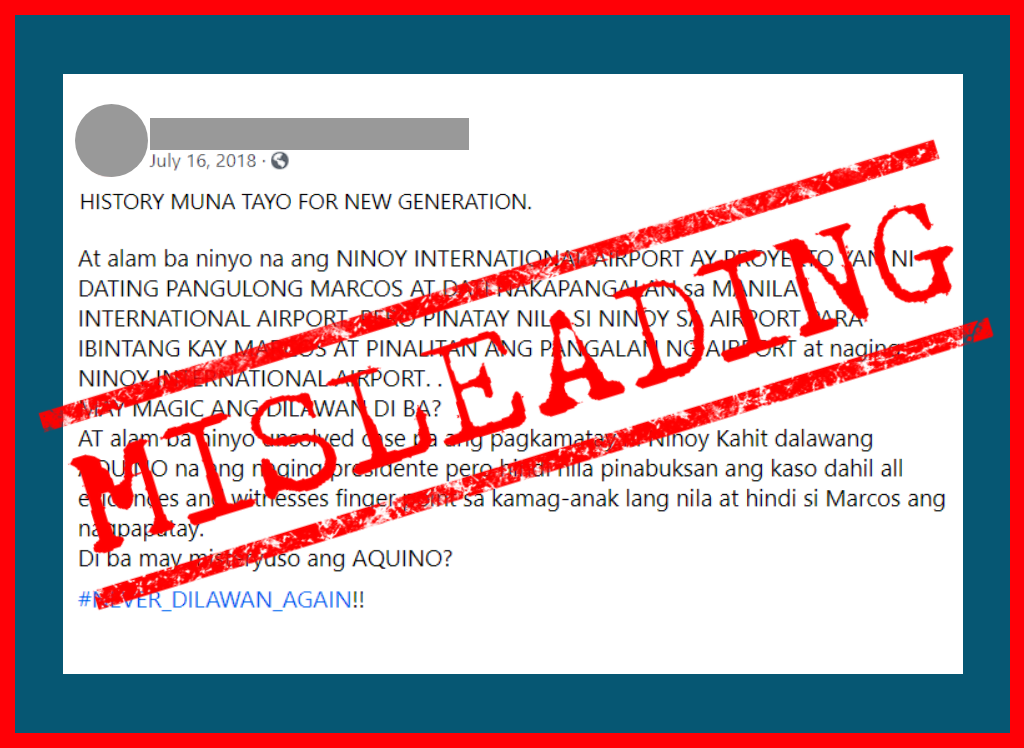

Within that collection is File No. 60, which documents Ferdinand E. Marcos’s claim of being a guerilla leader and founder of a guerilla unit called “Ang Manga Maharlika” with thousands of men in its roster from 1942 to 1945 in Northern Luzon. Marcos himself later changed it to “Ang Mga Maharlika.”

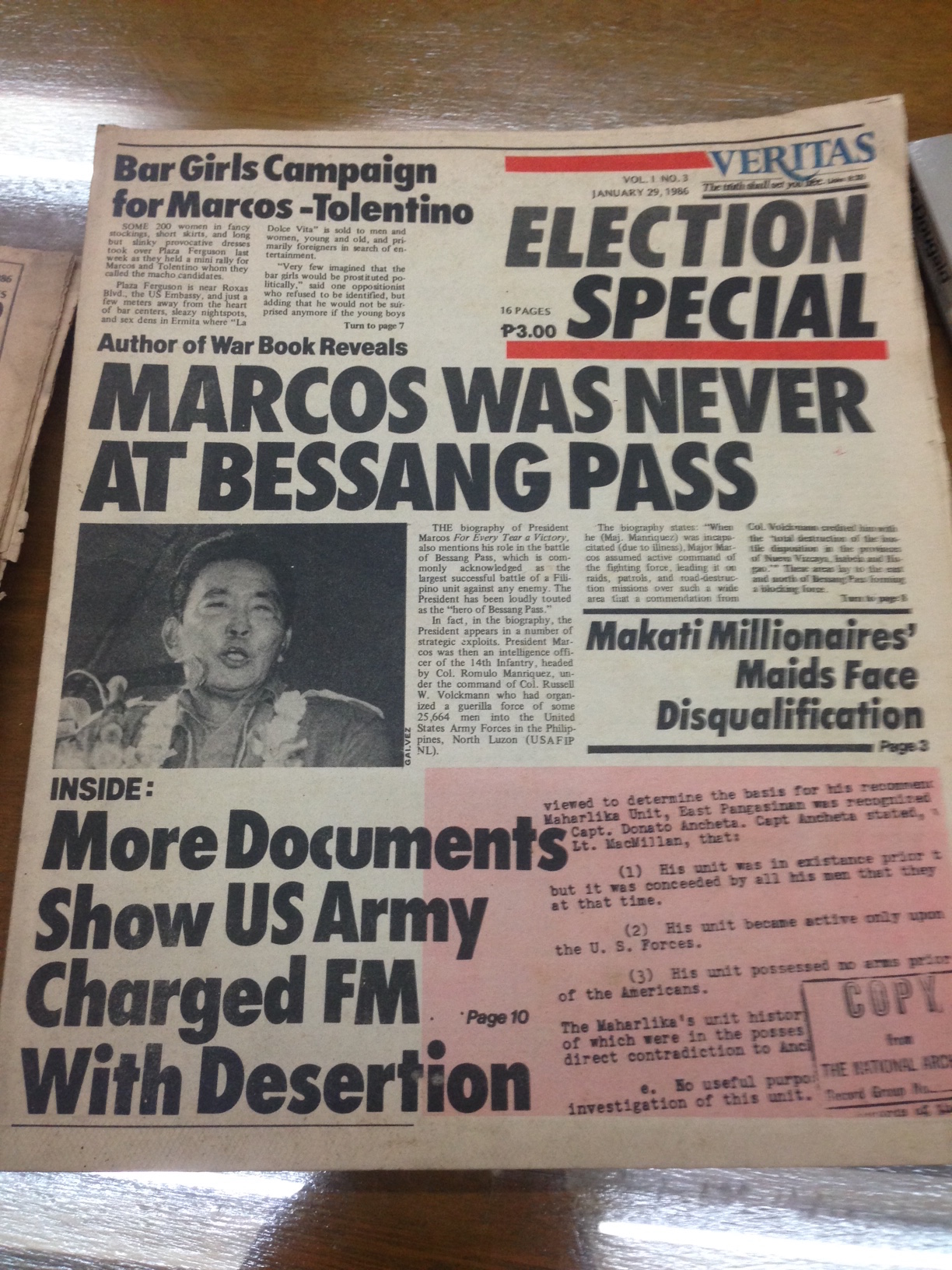

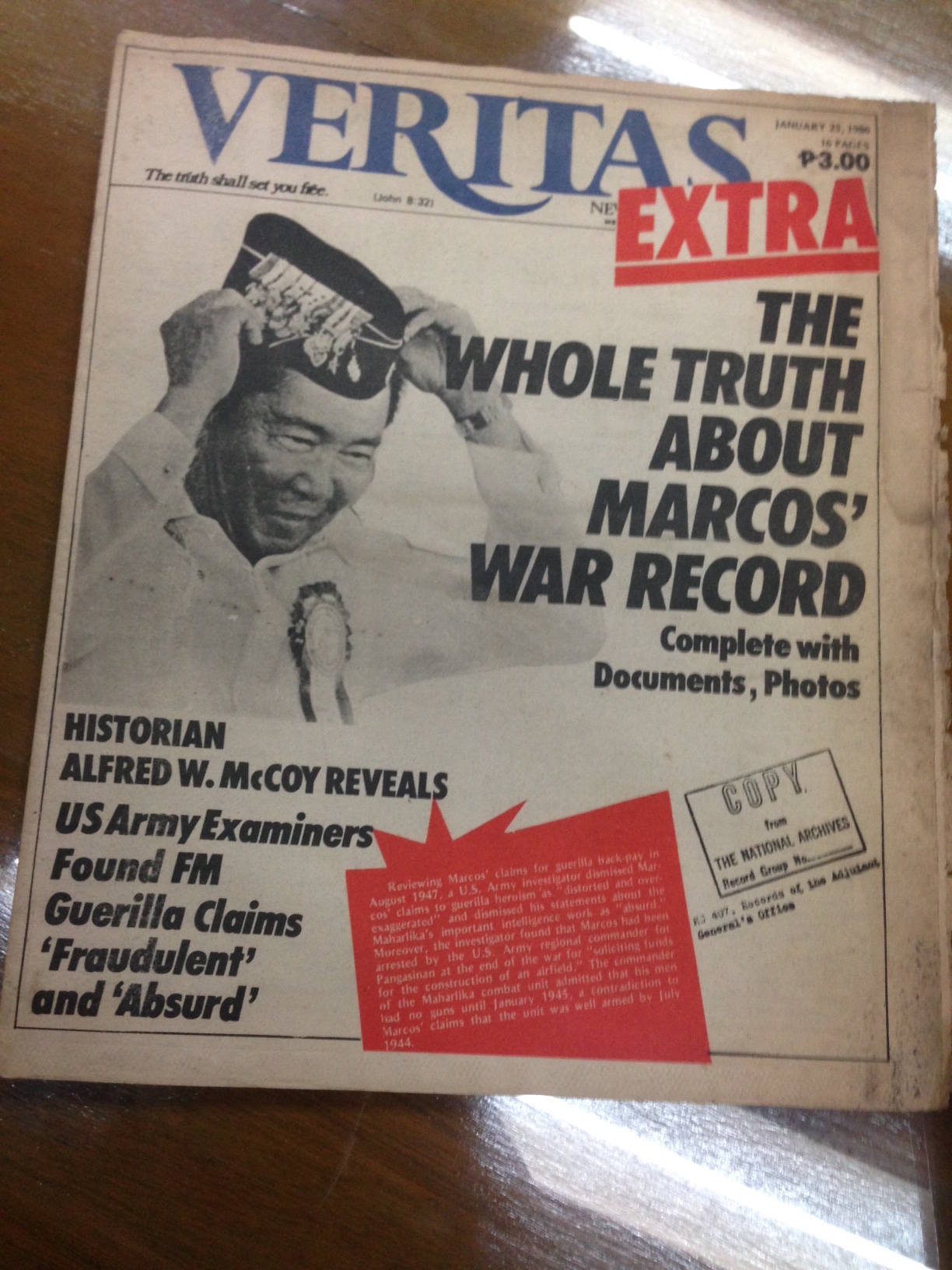

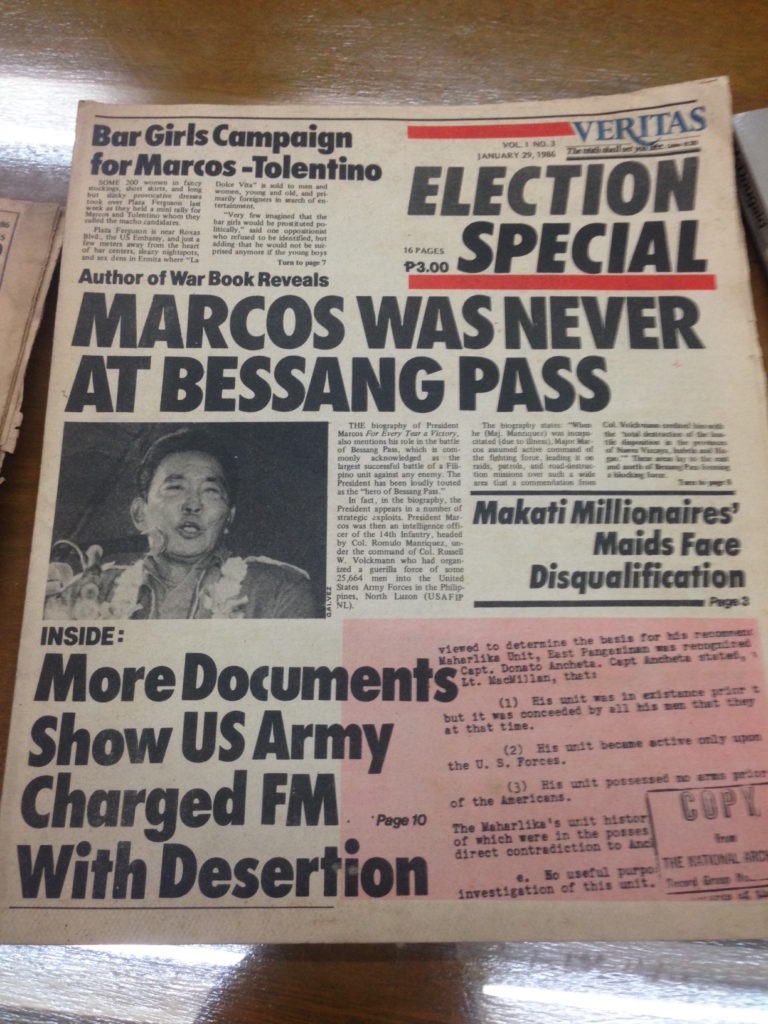

Included in the file’s more than 400 pages are the findings made by the U.S. Army which, after repeated investigations, repudiated Marcos’ claim and called it a lie.

Capt. Elbert R. Curtis, who handled Marcos’s claim for recognition for the most part of July 1947 to March 1948, came to two conclusions.

One, that “Ang Mga Maharlika Unit under the alleged command of Ferdinand Marcos is fraudulent.” Two, that “inserting his name on a roster other than the United States Armed Forces in the Philippines, Northern Luzon (USAFIP, NL) roster was a malicious criminal act.”

“It is also known that Marcos has enough political prestige to bring pressure to bear where it is needed for his own personal benefit,” Curtis said.

Before the Second World War, Marcos was known for two things—his acquittal for the murder of his father’s political rival Julio Nalundasan, and topping the 1939 bar exam while in jail for the crime.

In an interview with writer Gregorio Brillantes in 1968, Marcos claimed that after becoming a lawyer, he had wanted to embark on a “teaching career,” dreaming to be a professor at his alma mater, the University of the Philippines College of Law, “lecturing on some complex point of law.” Whatever his post-graduation plans really were, the war altered them.

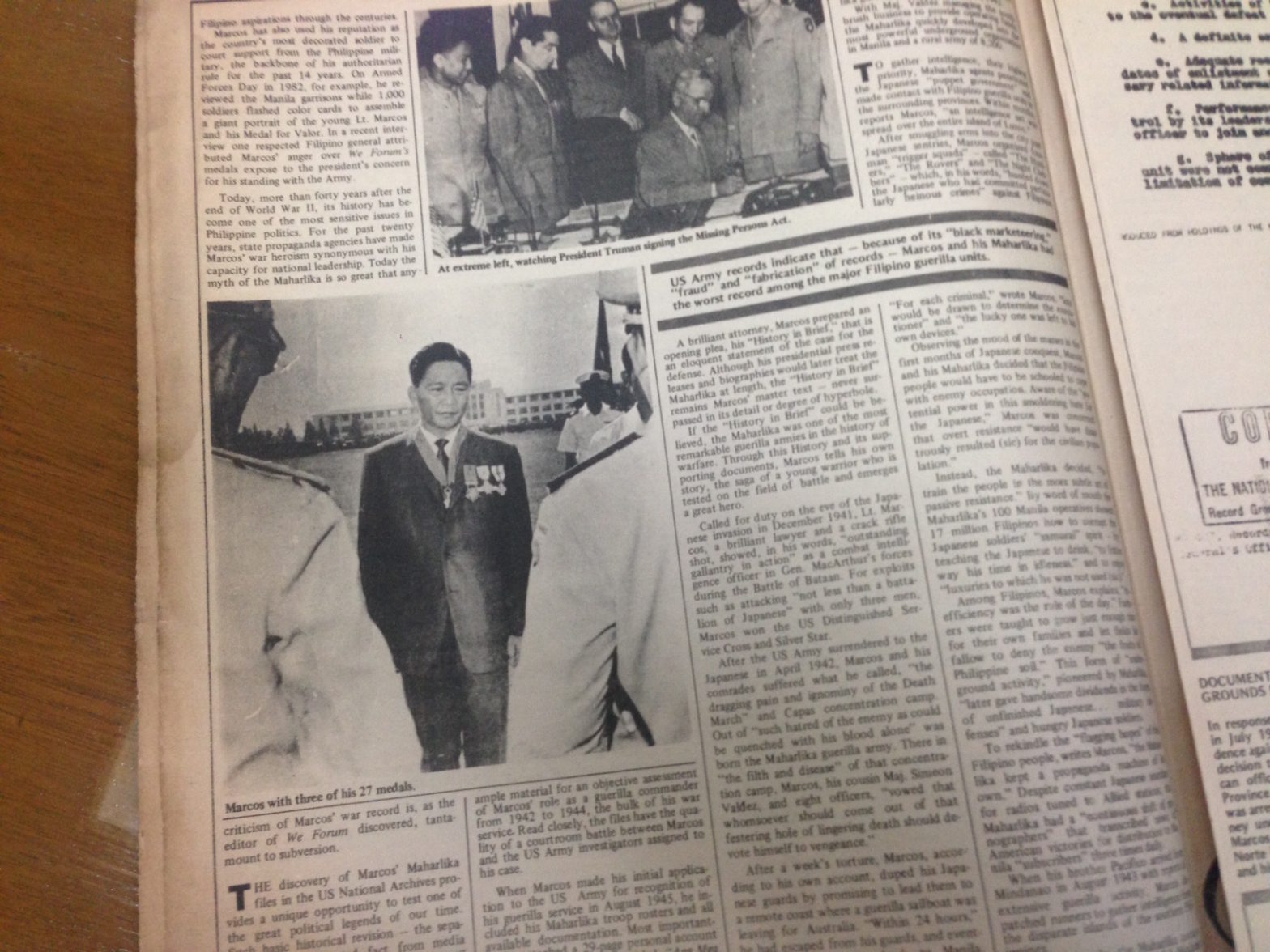

Marcos’s exploits in the World War II, real or imagined, became part of the narrative of his political career. In November 1941 he joined the army as a third lieutenant. He was with the Filipino forces in Bataan until their surrender in April 1942. With other prisoners of war, he was interred at Camp O’Donnell in Capas, Tarlac.

On August 4 the same year, he was released. There was a claim that it was due to failing health. But in his own commissioned biography, For Every Tear a Victory by Hartzell Spence, Marcos claimed that his mother Josefa “bribed the authorities to hasten her son’s freedom.”

Not much is known of Marcos’ activities from August 4, 1942 until December 12, 1944, when he joined the 14th Infantry, USAFIP, NL. If there was any indication of what he was up to, the records in File No. 60 point to one activity: taking advantage of the war times to line his pocket.

“Ferdinand Marcos was in San Quintin, Pangasinan, two or three months prior to the landing of the American forces, soliciting funds and guerilla help to construct a landing field in the vicinity,” the report said.

“The purpose of the landing field was to allow a plane to come in and evacuate General [Manuel] Roxas. Capt. Ray C. Hunt, commanding officer of PMD, LGAF placed Marcos under arrest for collecting money under false pretense. Gen. Roxas intervened on Marcos’ behalf and had him released to his custody,” it said.

The American forces reconquered Pangasinan in January 1945. Even before Marcos started his supposed activities in Pangasinan, on July 26, 1944 he sent a request to the returning American forces “for P100,000.00 Philippine currency and P500,000.00 Japanese war notes be sent his unit for maintenance.”

Marcos claimed to have 8,300 Ang Mga Maharlika members in North Luzon, Baguio, Zambales, and Manila. The investigator curtly noted that “this is entirely theoretical as no such unit ever existed.”

When Marcos ended his active service in 1946 he claimed to have gained the rank of major. Charles C. McDougald, in his book The Marcos File contested this claim, saying “The only promotion that Marcos could actually prove by official orders was his promotion to first lieutenant. All others, in addition to being contradictory and confusing, appear spurious.”

File No. 60 started with Marcos’s August 18, 1945 letter to the adjutant general of the Philippine Army requesting “that the complete roster of ‘Ang Manga Maharlika’ be approved and this organization be given recognition.”

The roster had 1,939 purported guerillas in active duty since December 1943. Guerillas recognized by the US Army received back pay for their efforts. The longer the period of their recognized participation in the war effort, the bigger their compensation.

On December 18, 1945, Marcos followed up on his original request for recognition. He also took the opportunity to provide additional materials to buttress his claim.

With this submission, listed as item number 6 in File No. 60, is the “Ang Mga Maharlika – Its History in Brief.” It was a history that not only chronicled the past and foretold the future but invented both points in time as well.

On June 7, 1947, a four-man military team told Marcos that based on the result of an initial investigation, his request for recognition was denied. The record of service he was claiming “was not substantiated by acceptable evidence.” The leadership, structure, effectiveness, and extent of the supposed guerilla unit were sketchy.

As for Marcos’s claim to leadership, the team said, “Performance of the unit did not indicate adequate control by its leaders because of the desertion of its commanding officer [i.e. Marcos] to join another unit.”

On July 16, 1947, Marcos, then in Washington, D.C. as member of the Philippine Veterans Commission, fired off a telegram to “strongly protest denial of recognition” and promised that he would file a formal petition.

It took him almost half a year to do this. The petition was filed on December 2, 1947. He tried to rebut the findings of the investigators point by point. His arguments ran for nine pages of single-spaced typescript with sixteen appendices. Ten of these were sworn and notarized affidavits of prominent and high-ranking military men in the newly established republic, a number of whom were also former leaders of well-known guerilla units during the war.

Listed as affiants supporting Marcos’s request for reconsideration were Brig. Gen. Macario Peralta Jr., commanding officer of the Panay guerillas; Maj. Gen. Rafael Jalandoni, chief of staff of the Armed Forces of the Philippines; Col. Vicente Umali and Col. Primitivo San Agustin Jr. of the President Quezon’s Own Guerilla; Maj. Leopoldo Guillermo, signal officer of the East Central Luzon Guerilla Area; Maj. Salvador Abcede of the Negros Guerillas; Consul-General Modesto Farolan of the Philippine Consulate at Hawaii; Col. Margarito Torralba, Armed Forces of the Philippines; and Narciso Ramos, minister-counselor of the Philippine Embassy in Washington, DC.

(to be continued)

The Third World Studies Center is making public File No. 60. Read it here <http://uptwsc.blogspot.com/2016/07/file-no-60-marcos-maharlika.html>

(Joel Ariate and Miguel Paolo Reyes are researchers at the Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines Diliman. Judith Camille E. Rosette provided research assistance in writing this article. The digital copy of File No. 60 came from Ricardo T. Jose, Ph.D., the center’s director and UP professor of history, recently named the UP Alumni Association’s Distinguished Alumnus Awardee in Historical Scholarship and Research for 2016.)