Text by MARIA FEONA IMPERIAL AND AVIGAIL OLARTE

Video by LUCILLE SODIPE

CLAD in white shirts and red bandanas bearing the famous peace sign, loyalists of the late strongman Ferdinand Marcos clutched the shut gates of the Libingan ng mga Bayani on Nov. 18, the day of the burial.

They wanted to be let in but the soldiers wouldn’t allow them.

That afternoon, braving the heat of the sun, nothing else mattered to the members of the Bagong Bansang Masagana (BBM), a group composed mostly of senior citizens who campaigned for Bongbong Marcos for the May elections.

Not even the rage of Marcos critics chanting, “Marcos, Hitler, Diktador, Tuta!” could stop them.

Barricaded by baton-wielding police officers, protesters and loyalists shouted at each other some 200 meters away from the gates.

“Dapat kayo ilibing ng buhay (You should be buried alive),” one of the supporters shouted at anti-Marcos protesters, composed mostly of youth.

As rage rippled out from the crowd, two middle-aged women brought out cans of fresh red paint and laid on the pavement a piece of black cloth.

They painted the words: “WE’LL BE BACK. HERE LIES EVIL.”

The area was gradually cleared of protesters as dusk fell. But they left a message: a graffiti bearing the names of those who disappeared, were raped or tortured and killed during Martial Law: Eman Lacaba, Lorena Barros, Archimedes Trajano, Edgar Jopson, Lean Alejandro, among many others.

But this doesn’t matter to Ester Dayandante, president of BBM, who believes all the allegations against Marcos and his family are lies.

“Mga batang nagsisigaw na kalaban namin, na mga dilawan, walang alam. Ang binasa nilang libro hindi mo alam kung laman (kung) puro kasinungalingan (Those young people who are against us, they belong to the yellow camp; they’ve read books full of lies).”

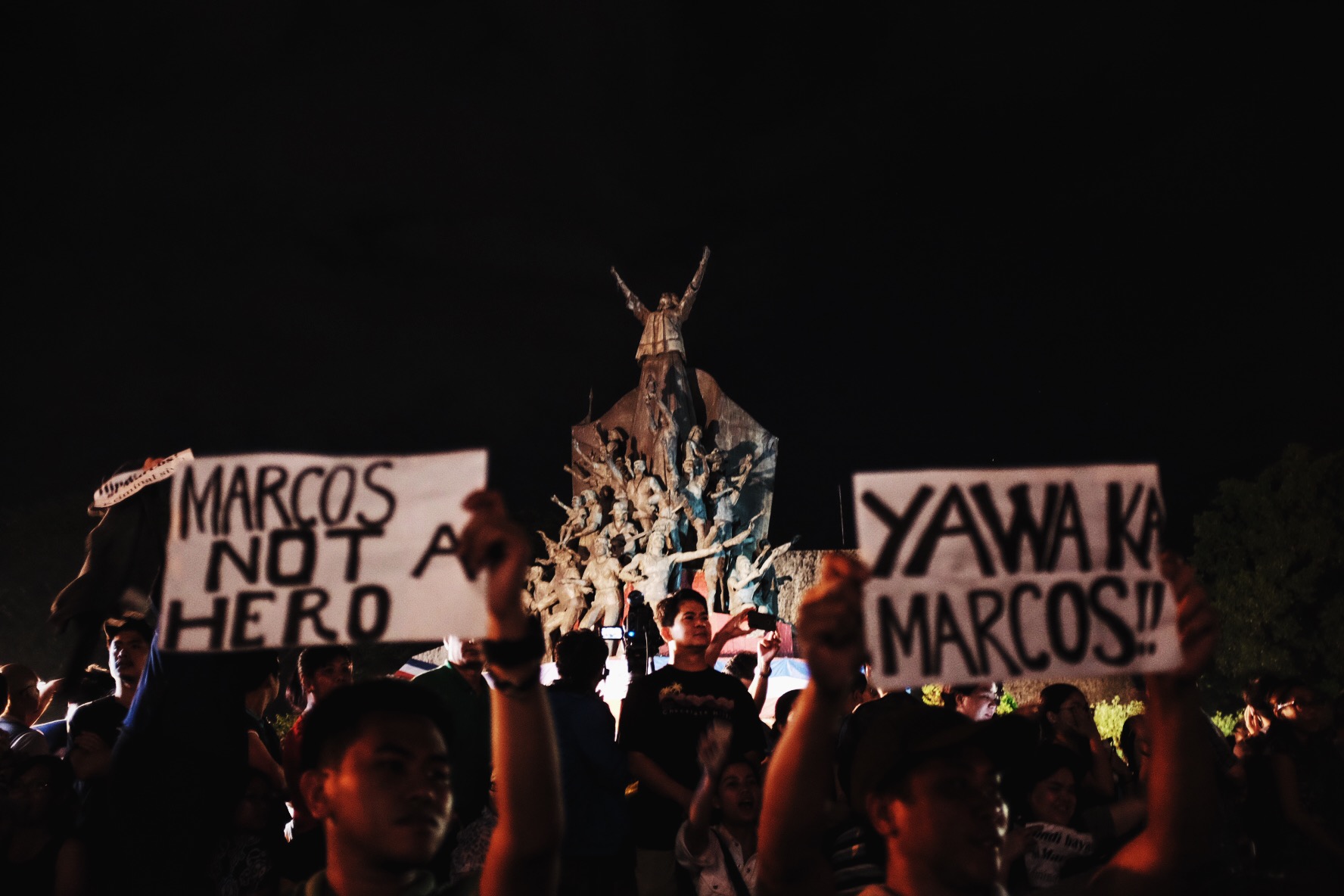

For them it was day of victory, but not to thousands more who staged several protests all over Metro Manila. Hundreds of angry protesters gathered at the historic People Power Monument on the evening of Nov. 18, to express their rage over the burial of Marcos, which they said was done in secrecy and haste.

The youth, members of the Church and the academe, Martial law victims, and human rights activists cried, “Hukayin, hukayin (Dig him up)!”

They waved flags and placards bearing the words, “Marcos magnanakaw, hanggang sa huli (Marcos a thief till the very end)!” They also held a noise barrage, yelling at cars passing by Edsa, whose drivers honked horns in support of the rally.

Even five-year-old Gavin gamely held up a poster that read: “Marcos, diktador! Hindi bayani (Marcos a dictator, Marcos not a hero)!”

He was with his grandmother, Corazon Estojero, along with other members of the Families of Victims of Involuntary Disappearance (FIND), a group of advocates whose loved ones were taken during the dark years of martial rule.

November 17th was the day the husband of Estojero disappeared. To this day, decades after the horrors of Martial rule, she refuses to hold a ceremony for his burial.

She is a widow who refuses to grieve, she is a mother who continues to fight.

“Hindi namin siya titigilan. Ipagpapatuloy namin ang laban (We won’t let this be, we won’t stop fighting),” said Estojero, an activist during the Marcos years herself.

Another martial law victim, Mar Sarmiento, was just as angry.

“I want him dug up and dumped in Payatas (garbage site),” said Sarmiento, who was taken into custody by at Camp Crame, detained for no reason, and tortured for six months.

He believes he was held in detention because his father was a journalist and a friend of Primitivo Mijares, author of the book, “The Conjugal Dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos and Imelda Marcos,” published in 1976.

The trauma has stayed with him, and he wants nothing more than a future free of fear and oppression for his daughter.

“All we can do now is hope for (another) president who will share our sentiment,” he said, adding that President Rodrigo Duterte, who ordered and allowed the burial of Marcos at the Heroes’ cemetery, is not a setting a good example for the millennials.

Jim Paredes, one of the most popular figures at the EDSA People Power in 1986, offered an advice to the youth.

“Sa mga millennial, ipinaglaban namin ang freedom of speech at freedom of assembly noong panahon ni Marcos (To the millennials, we fought for freedom of speech and freedom of assembly during the time of Marcos),” Paredes said, “Dapat ipagpatuloy ninyo ito (Make sure you will continue to enjoy these rights).”

Paredes and the protesters all want the Marcoses to apologize for their sins, for the killings and torture under the Marcos regime, and for the family to return the ill-gotten wealth they had allegedly amassed.

As for Estojero and other martial law victims, the burial of Marcos is perhaps a fate worse than death, as they continue to suffer from the loss of their friends and loved ones who are probably buried in nameless, unknown graves – the real heroes who fought against a dictator whose “last wish” had now been fulfilled.