The fear of many during the 2022 elections campaign that a Bongbong Marcos presidency would lead to more Marcos Sr. “glory days” propaganda has come true.

A “new” Marcos Memorial hospital

Among the active advertisements for bids one can view at the Department of Public Works and Highways website, one will find documents regarding civil works for a Pres. Ferdinand Edralin Marcos Memorial Hospital in Lamut, Ifugao. The bid invitation states that the project’s approved budget for contract is almost PHP 20 million. The contract involves earthwork and the construction of a reinforced concrete structure.

It’s hardly an issue that a fourth-class municipality is set to have one more functional health facility, but the name is a curiosity—there is no Pres. Ferdinand Edralin Marcos Memorial Hospital in the current online version of the National Health Facility Registry. The name does, however, show up in a document detailing the allotments for the FY 2025 Health Facilities Enhancement Program of the Department of Health. Is the hospital one of the numerous (at least 143) public structures and spaces named after a member of the Marcos family during the Marcos dictatorship, or is it a new facility?

Based on readily available sources, the project is an attempt to revive what was supposedly called the Major Ferdinand Edralin Marcos Emergency Hospital in Lamut. According to Senate Bill no. 1370, filed by Sen. Imee Marcos in October 2022, that hospital was “abandoned by the provincial government” sometime in 2010. Imee’s bill seeks to establish in Mayoyao, Ifugao, a hospital to be known as the Eastern Cordillera Regional Hospital, integrating into that the Major Ferdinand Edralin Marcos Emergency Hospital, “retaining its name as such.” The explanatory note of the House counterpart bill, House Bill no. 3786, filed by Ifugao Rep. Solomon R. Chungalao and Marcos clan members Ferdinand Alexander “Sandro” Marcos III and Angelo Marcos Barba, noted that the bill had been refiled twice, getting House approval during the 18th Congress. However, the status of both the current Senate and House bills is “pending with committee.”

It is unclear when “Major” became “President” and “Emergency” was changed to “Memorial.” The Local Government Code allows LGUs to rename “provincial hospitals, health centers, and other health facilities” within their territorial jurisdiction. The insistence on keeping the name may be strengthened since the restoration of the hospital is finally making headway under another Marcos administration.

Dubious heroic narrative

Moreover, Chungalao is a firm believer in the wartime heroism of Major Ferdinand E. Marcos. In May 2023, he filed another bill, HB no. 7989, which aimed solely to restore and rehabilitate the Lamut hospital. In the bill’s explanatory note, Chungalao said that the hospital was built on the site where Marcos Sr. was once critically wounded while being chased by Japanese soldiers. A man named Hodom (surnamed Bannawol) supposedly “found him and decided to cover him in grass so that the pursuing Japanese soldiers will not see and catch him.”

Hodom, the story continues, along with his “barangay-mates,” retrieved the grass-covered Marcos at nighttime “and brought him to their home and nurtured him back to continue his guerilla activities.” Chungalao claimed that the hospital was specifically requested by Hodom when Marcos, as president (more like datu or sultan) asked the Ifugao elder what he could do to reward his rescuers. Capping off his tale, Chungalao said that after the EDSA Revolution, the hospital was stripped of the Marcos name, becoming the Panopdopan District Hospital, named after the barangay where it is located. In 2010, the hospital relocated to another site—outside Barangay Panopdopan but retaining the name—leaving, as Imee said, the original facility abandoned. Chungalao’s bill aimed to revive the rotting facility as “a testament of the former president’s heroic services during the Second World War.”

Capt. Vicente Rivera of the 14th Infantry, Marcos’s guerrilla unit from December 1944 until the conclusion of the war, told Bonifacio Gillego, writer of exposes on Marcos’s wartime record, that Marcos never participated in combat operations during his time with the 14th. The unit’s rosters clearly state that Marcos was a non-combat (S-5, or civil affairs) officer based in their headquarters in Bagabag, Nueva Vizcaya when the adventure in Panopdopan—about 30 kilometers away—supposedly took place.

Setting aside the questionability of Marcos Sr.’s alleged exploits, there is no law, whether a Republic Act or a Presidential Decree, creating a Ferdinand Marcos hospital in Ifugao. There is no General Appropriations Act, particularly those enacted during the Marcos Sr. years, stating that there was a Major Ferdinand Edralin Marcos Emergency Hospital in that province; there was a Pres. Ferdinand E. Marcos Emergency Hospital in Diffun, Quirino, which is now called the Diffun District Hospital. A Panopdopan Emergency Hospital does appear in GAAs enacted before the EDSA Revolution.

Perhaps the Panopdopan facility used to be colloquially referred to as the Ferdinand Marcos Hospital. It may very well have been the hospital’s intended name, considering that it was created as a field hospital under what was then called the Major Ferdinand E. Marcos Veterans Regional Hospital in Bayombong, Nueva Vizcaya, as per Presidential Decree no. 306—an instance of Marcos Sr. using his dictatorial powers to affirm the naming of a hospital after himself. The two formally named pre-EDSA Ferdinand Marcos hospitals were rechristened by the Corazon Aquino administration via Memorandum Order no. 48, issued in November 1986. The order, which changed the name of several government hospitals named after one of the Marcoses or are very closely associated with them, does not mention any Marcos-named hospitals anywhere in Ifugao.

It can thus be argued that the “resurrected” Pres. Ferdinand Edralin Marcos Memorial Hospital in Ifugao will be the first such facility formally named after the dictator in that province.

Public funds used to perpetuate Marcos Sr. myth

This is but one recent case of a government project done or planned under Marcos Jr.’s administration that used or intends to use public funds to build something that honors his father.

In February 2023, there was groundbreaking ceremony for the construction of the Ferdinand E. Marcos Grandstand in Camp Capt. Valentin S. Juan (the Ilocos Norte Police Provincial Office) in Laoag, Ilocos Norte reportedly funded by the Office of the Ilocos Norte First District Rep. Sandro Marcos, and is under an Ilocos Norte provincial police program called Better, Brighter, and Model PPO 2023 and Beyond—BBM 2023 and Beyond, for short. Sandro attended both the February groundbreaking ceremony and the inauguration of the grandstand on Sept. 11, 2023, the 106th birth anniversary of his paternal grandfather.

Memorial Markers

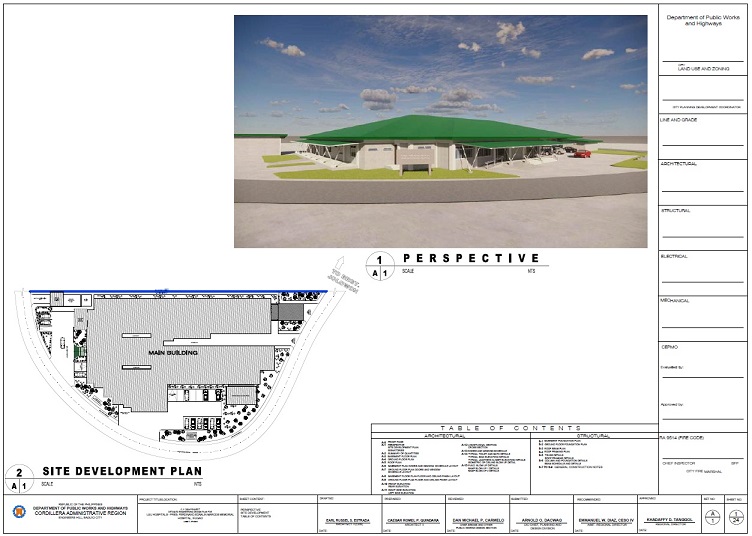

Ilocos Norte is, of course, already peppered with structures and memorials honoring the Marcoses—another one, built using funds controlled by someone sometimes referred to as “Ferdinand Marcos III,” is unsurprising. The same can be said about the planned Marcos Monument in San Esteban, Ilocos Sur—still being in the so-called pro-Marcos Solid North—which seeks to reinforce an utterly fictional connection between Marcos Sr. and an important wartime activity. After reporting on the planned monument—and debunking the false war stories connected to it—in May 2023, members of the UP Third World Studies Center were able to visit the planned memorial site in August that same year. It appeared that there was no progress on the monument at that time after the groundbreaking ceremonies held in April 2023.

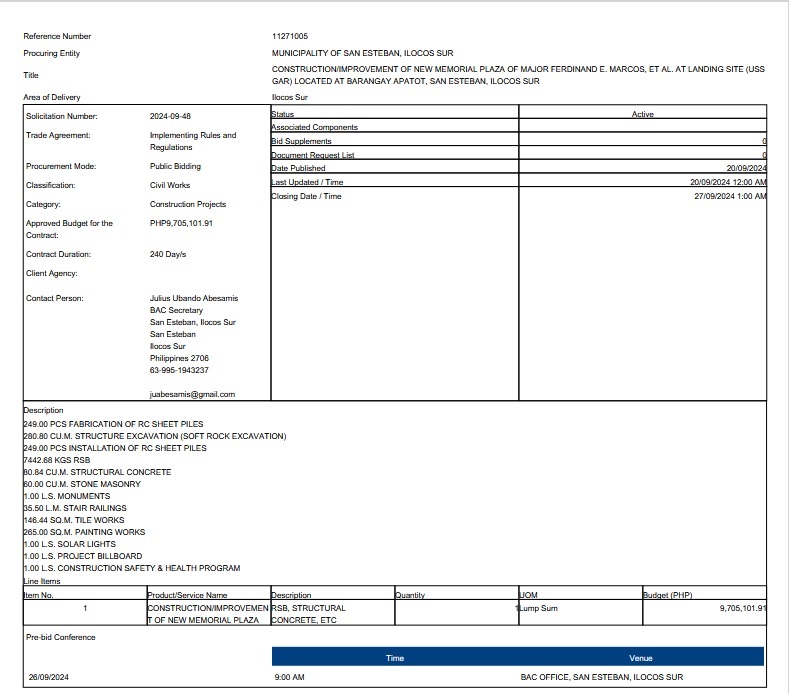

However, based on publicly accessible bid documents (e.g., from the international contract opportunity website tendernews.com), the project—titled “Construction/Improvement of New Memorial Plaza of Major Ferdinand E. Marcos, et al. at Landing Site (USS Gar) Located at Barangay Apatot, San Esteban, Ilocos Sur”—is pushing through. Last year, the municipality of San Esteban allocated over PHP 9.5 million for the project—quite a sum for a fifth-class municipality.

Bid-related document on the New Memorial Plaza of Maj. Ferdinand E. Marcos, et al., in Apatot, San Esteban, Ilocos Sur .From Tendernews.com.

If it is completed within 2025, the San Esteban memorial may become the second monument to Ferdinand Sr. built with public money during Ferdinand Jr.’s presidency. The first one is the Pantabangan Dam marker in Nueva Ecija, which was completed sometime in early 2023. An older marker remains on the site as well.

About a sixth of the road-facing side of the marker—which is approximately six feet tall and eight feet wide, atop a two-step platform—is occupied by a smiling portrait of Marcos Sr., beneath which are his name and the years of his presidency in big, bold characters, about sixty font sizes bigger than the rest of the marker’s text. The marker highlights that it was put up during the tenure of several National Irrigation Administration officials, including NIA Acting Administrator Eduardo “Eddie” Guillen. Bongbong appointed Guillen, a former mayor of Piddig, Ilocos Norte, to that position in December 2022.

Though the marker’s text does say that funding for the dam came largely from foreign loans and that a pre-dictatorship law, Republic Act no. 5499, authorized the construction of the dam, the marker makes it seem that the massive infrastructure project would not have been realized were it not for Ferdinand Sr.—as if the money came from his pockets and he personally directed the dam’s construction.

Marcos Field, Marcos Parks

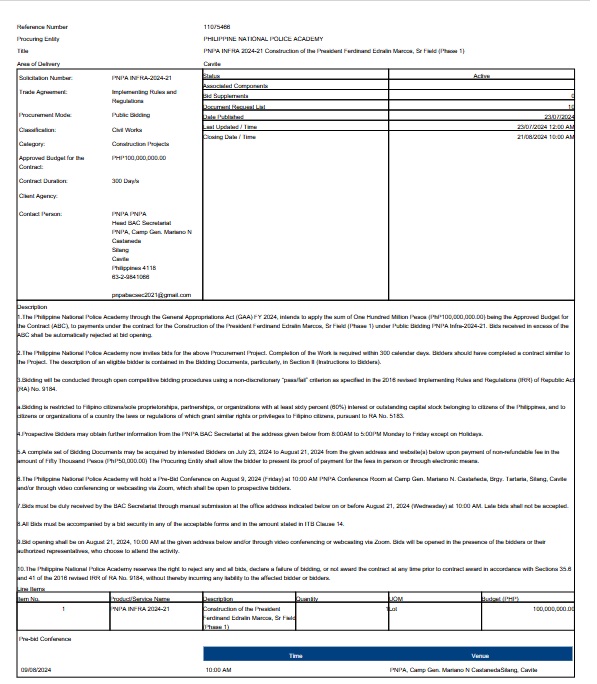

The four projects mentioned so far, however, are dwarfed in terms of cost, and possibly scale, by the planned President Ferdinand E. Marcos Sr. Field at the Philippine National Police Academy in Silang, Cavite. Based on documents downloadable from the DPWH website, part of the project will use DPWH funds—with a PHP 9.65 million approved budget for contract—for earthworks and plain and reinforced concrete works. Specifically, it is part of the allocation for the Construction/Improvement of Various Infrastructures in Support of National Security program (in Filipino: Tatag ng Imprastraktura para sa Kapayapaan at Seguridad, or TIKAS).

Another document, downloadable from tendernews.com, states that the ABC for the project named “PNPA INFRA 2024-21 Construction of the President Ferdinand Edralin Marcos, Sr. Field (Phase 1)” is PHP 100 million. That was set to come out of the PNPA’s funding under the 2024 GAA. The document states that the bid opening was scheduled on August 21 last year.

PNPA Marcos Field

PNPA director PMGen. Eric Noble first announced that the PNPA’s parade grounds will be expanded and renamed into Marcos Field in March 2023, during the 44th Commencement

Exercises of the PNPA. According to the Philippine Daily Inquirer, Noble “highlighted Marcos Sr.’s contribution to the academy, mentioning Presidential Decree No. 1780, which provides the PNPA with an academic chapter and expanded curricular programs.”

A groundbreaking ceremony for the field was held in July 2024. The guest of honor was Sen. Imee. According to a Philippine Information Agency article, “The construction of the President Ferdinand Edralin Marcos Sr. Field is dedicated and named to the former president who is considered and acknowledged as the ‘Father of the PNPA.’” The article also said that the grounds “will be equipped with a 2-story grandstand with the size of 30M x 160M [with the] ground floor [serving] as a holding and receiving area with a VIP room and conference rooms,” and the second floor serving as “the stage with a VIP room, an audiovisual room, an office, and bleachers which can accommodate approximately 1,200 seats.”

Based on pictures of the field’s planned features, which can be seen in the background of photos of the groundbreaking, the project also entails the construction of yet another Ferdinand Marcos Sr. monument, much bigger and more elaborate than the Pantabangan one is or the San Esteban one can ever hope to be. The current plan appears to involve a huge full-body portrait or relief of Ferdinand Sr. with the colors of the Philippine flag in the background, integrated into a structure that looks like a cumbersome crest-shaped headdress, fronted by an altar-like table on a raised platform. It resembles a contemporary Catholic church sanctuary, with the dictator standing in for the Christ on the crucifix.

Arguably, former Philippine Constabulary/Integrated National Police chief Fidel Ramos also has a right to be called the father of the PNPA, at least based on propaganda made in favor of him. A book titled 12 years of Leadership, Commitment and Achievements, published by the Headquarters of the PC/INP in 1984, many of the pieces of legislation on police matters were in fact drafted by Ramos and/or representatives of the police. It also says that Ramos “set up the Integrated National Police Training Command” in 1976, which preceded the creation of the PNPA. The website of the PNPA class of 1996 notes that after the enactment of PD no. 1184, which created the PNPA, Ramos “created a study committee to prepare the corresponding feasibility study and all other prerequisites for the activation of the envisioned police academy.” Lastly, the PNPA relocated to its current site in Cavite in 1994, when Ramos was president.

150-hectare Marcos Park in Rizal province

If there is at least one upcoming Marcos Field, there is also a new “Marcos Park” in the works. In statements made to the media in January 2024, Secretary Jose Acuzar of the Department of Human Settlements and Urban Development, said that the Pasig River Promenade, part of the Pasig River Urban Development, will lead to a 150-hectare park in Rizal province, which may be called “Marcos Park.” The current PHP 18 billion Pasig River rehabilitation project is reportedly funded solely via donations from private entities. according to Acuzar. Envisioned to be like New York’s Central Park, Acuzar said it will be named after Marcos “kasi siya ang nagpagawa” (he, Bongbong, ordered it built).

Apparently, that will likely be the second Marcos Park built under Bongbong’s term. The first is the facility in the Pambansang Pabahay para sa Pilipino Housing program site in Barangay Vista Alegre, Bacolod City. Back in December 2023, Acuzar said that a park to be constructed in the site was dubbed by his department as “Marcos Park.” The first units in the site were turned over, after a number of delays, in December 2024.

Marcos Museums and Military Honors

In May 2023, the Malacañang Heritage Mansions became open to the public. Among them is Bahay Ugnayan, which “invites visitors to explore the personal and political journey of President Ferdinand ‘Bongbong’ Marcos Jr.,” decribed as “a man whose destiny is intertwined with the nation’s history.”

The Teus Mansion, meanwhile, features a museum of Philippine presidents. The largest room therein is dedicated to the Marcos Sr. administration; all other presidents share a room. The brief biographical note about Marcos Sr. in the museum reiterates the false claim that he obtained a score of 98.01 in the 1939 bar examinations, and claims that the “threat of Communist insurgency as well as the protests against his administration” were the sole reasons for the imposition of martial law in 1972. It also brushes off many details about his ouster, simply stating that “A few weeks [after the 1986 snap election], on 25 February 1986, Marcos and his family were exiled to Honolulu, Hawaii.”

The timeline of events in the “Marcos room” of the museum does provide more details—such as the vote snatching during the election, the walk out of the Comelec computer operators due to “anomalous vote counting,” and even the February 11, 1986 assassination of anti-Marcos Antique governor Evelio Javier—but overall, the artwork and memorabilia-filled exhibit tries to stay “neutral” about Marcos Sr.

Based on photos, the presidential museum in the Baguio Mansion House, inaugurated by First Lady Liza Araneta-Marcos in September 2024, is more of the same—portraits, busts, and (ghostwritten) books of the dictator can be found in the Marcos Sr. section of the museum. Moreover, the museum features not one President Marcos but two: the Baguio mansion also has a small Bongbong Marcos exhibit. The DPWH Cordillera Administrative Region’s annual procurement plan for civil works and consulting services, dated June 30, 2024, includes a line item partly for the “Rehabilitation and Improvement of the Mansion House,” with an estimated budget of PHP 100,000.00. The source of funds indicated is the Office of the President.

Another Malacañang mansion was renovated in 2024, but it is not open to the public. The Laperal Mansion has been designated the Presidential Guest House, and features themed rooms for every president before Bongbong. Based on photos, the biggest suite is the Ferdinand E. Marcos one. The brief description of Marcos Sr. in the Laperal Mansion website depicts the dictator as a truly productive president—“In his time, the Philippines saw a boom in infrastructure, farming and arts”—and a loving family man—“He was known to step out of cabinet meetings when he would hear one of his children crying.”

At least one other Marcos-associated museum was renovated in 2024. The Marikina Shoe Museum has long been tied to Imelda, since it houses some of the pairs from her infamous shoe collection. However, when a team of researchers from the UP Third World Studies Center visited the museum in September 2023, Imelda’s shoes and a few small framed photographs of her were confined to the museum’s mezzanine; previous photographs of the museum prior to 2019 showed that it had a number of unmissable paintings of Imelda, which didn’t exactly highlight her connection to the Marikina shoe industry. The paintings were restored in 2024, and her shoes and photographs were placed in a much more prominent location on the first floor. A terno of Imelda alongside a barong of Marcos Sr. can still be found on the mezzanine.

According a February 2019 post by the Marikina Public Information Office Facebook page, Mayor Marcy Teodoro caused the previous changes in the museum’s exhibits that resulted in the removal of Imelda’s paintings, stating, “Mas magiging makabuluhan ang ating shoe museum kung sa pagbisita rito ng mga naglalakbay aral ay may kaalaman, kamalayan at karanasan silang iuuwi at yayakapin.” In 2024, he not only brought the paintings back, he also hosted the museum’s relaunching in July with Imelda herself and Liza Araneta-Marcos.

Bongbong rocket

Besides these museums connected to the first ladies surnamed Marcos, last year also saw the opening of museums with exhibits praising the Marcoses that are tied to a somewhat less glamorous arm of the state—the military. There is the Military Park in Camp Cape Bojeador in Burgos, Ilocos Norte, which was inaugurated in January 2024. Among the exhibits are replicated remnants of the Marcos era Self-Reliance Defense Posture program, including a launcher for the failed “Bongbong rocket” program.

Interestingly, that was not the only government-backed appearance of the rocket named after the president last year. Among the exhibits at the lobby of the Philippine International Convention Center during the celebration of the 74th birthday of the Philippine Marine Corps, held on Nov. 7, 2024, was a model Bongbong rocket. A little over a month later, Bongbong led the relaunch of the Armed Forces of the Philippines museum. Among the museum’s centerpieces is yet another Bongbong rocket, which the president gamely posed for pictures with. Never mind that the missile program fizzled out well before the Marcos dictatorship ended, producing projectiles dismissed by Americans as “Roman candles.”

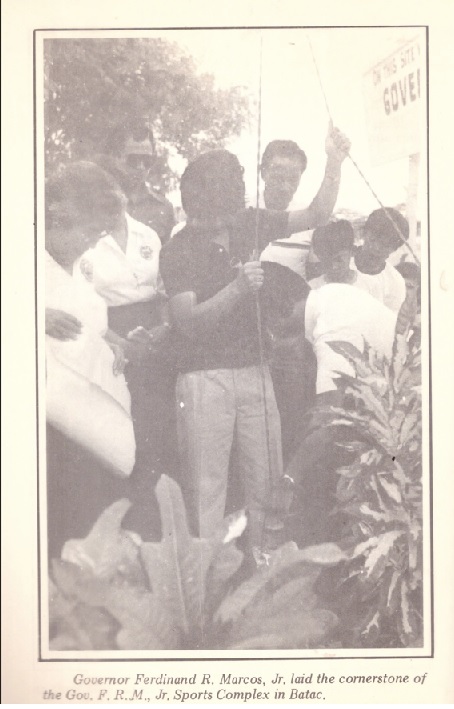

Were it not for the EDSA Revolution, Bongbong would have long had something named after him besides the ill-fated rockets. In September 1983, the Sangguniang Bayan of Batac, Ilocos Norte adopted Resolution no. 113, “Declaring the Batac Sports Complex as Governor Ferdinand (Bongbong) R. Marcos Jr. Sports Complex.”

The text of the resolution does not explain why the facility, still to be constructed, was to be named after the newly installed governor, a living person, possibly in violation of Republic Act no. 1059.

Bongbong did not seem to mind; he even attended the groundbreaking ceremony for the complex. The facility was to be partly funded by donations (notably from the Annak ti Batac chapters of Northern California and Hawaii) but some municipal resolutions (e.g., Resolution no. 50, s. 1984) show that public funds were also appropriated for the project. Come April 1986, however, the Sangguniang Bayan was well aware that they could not make any further progress with the project; Resolution no. 38, s. 1986 resolved to simply construct a commemorative marker on the site of the complex that never was, though the text of the resolution called it the “Batac Sports Complex.”

Marcos tank

One other piece of military hardware—functional this time—named after a Marcos showed up between 2023 and 2024. Photos of a light tank bearing the name Maj. Ferdinand E. Marcos started showing up on social media in late 2023. The Armor Division of the Philippine Army also posted a photo of it in July 2024. Finally, in December last year, during the commemoration of the 89th anniversary of the AFP, the Marcos tank was displayed at the Lapu-Lapu Grandstand in Camp Aguinaldo, with a panel board highlighting Marcos Sr.’s status as a recipient of the Medal for Valor—the basis for which has long been deemed dubious by historians such as Ricardo Jose and writer Charles C. McDougald.

If one also counts the commemorative stamp for the fiftieth anniversary of the Labor Code, featuring both former labor secretary Blas Ople and Marcos Sr., released in May 2024, overall, last year, there were about a dozen government or government-supervised projects that were announced, ongoing, or completed that are meant to honor the Marcoses, in addition to several that were completed in 2023.

Paoay museum

Imee is certainly no stranger to using government funds to honor her father. Back when she was governor of Ilocos Norte between 2010 and 2019, she commissioned heritage specialist Eric Zerrudo—currently executive director of the National Commission for Culture and the Arts—to curate the exhibits of Malacañang of the North in Paoay, Ilocos Norte, highlighting the achievements during the Marcos Sr. years. In 2017, over the course of a House Committee on Good Government investigation looking into alleged anomalous transactions involving the Ilocos Norte Provincial Government, Zerrudo made a startling claim: he did not know that the project was government funded, believing it was paid for by the Marcos family—in fact, he said he received his and his company’s payment in cash, given by Imee herself. Thus, he claimed that his purported signatures on bid documents were falsified. As of this writing, there is no reported resolution to this matter, or any of the other anomalies and irregularities involving then Governor Imee that were uncovered almost eight years ago, even if legislators back then were considering filing plunder charges against her.

In 2019, she filed a bill to modernize Mariano Marcos State University and to turn it into Ferdinand E. Marcos State University. The objective of that legislation can still be achieved if she is reelected.

Who can stop the continued glorification of Marcos Sr. using false narratives?

The National Historical Commission of the Philippines is the primary government agency responsible for history and has the authority to determine all factual matters relating to official Philippine history.

During the Duterte administration, it tried to halt but failed the burial Marcos Sr. at the Libingan ng mga Bayani, approved a fairly neutral historical about him, and opposed a bill that aimed to make the dictator’s birthday “Marcos Day” in Ilocos Norte.

Surely, the Commission would not want it inscribed in history as having abandoned its mandate simply because the president is another Marcos.

*Miguel Paolo P. Reyes is a University Research Associate at the Third World Studies Center (TWSC), College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines Diliman, and a lecturer at the same university’s Department of English and Comparative Literature.

Joel Ariate Jr. provided research assistance for this article. Field work in Ilocos Sur and the Malacañang Mansions were conducted by Larah Vinda Del Mundo and Nixcharl Noriega; in Nueva Ecija, by Reyes and Ariate; and in Marikina by Reyes, Del Mundo, and Ariate. This piece is part of TWSC’s ongoing Marcos Regime Research program.

###