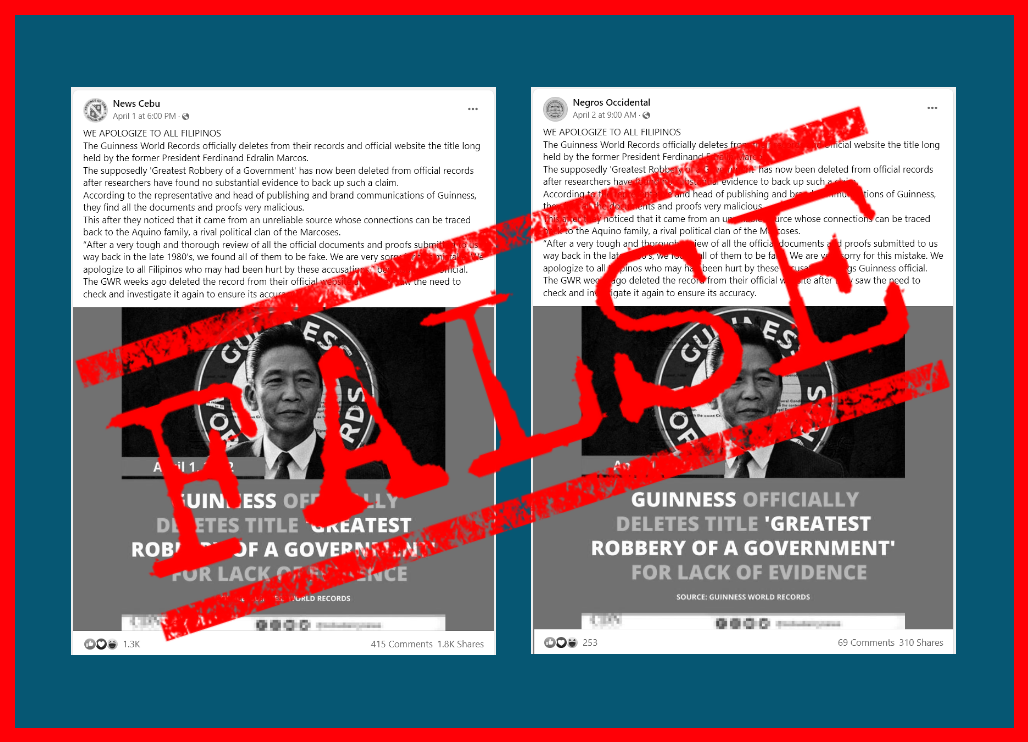

A monument being built in a town in Ilocos Sur tries to connect the late president Ferdinand E. Marcos to a wartime heroic operation that has no factual record of his participation.

The designation of the landing site of the USS Gar submarine, which brought armaments that led to the defeat of the Japanese Imperial army in the same site as the Marcos monument, raises questions because a historical marker on the same operation exists in another site.

Groundbreaking ceremony in San Esteban

The monument had a groundbreaking ceremony on April 20 in San Esteban, a seaside town in Ilocos Sur.

The event was among the events during the town’s fourth Seafood Festival. In attendance were Provincial Board Member Evaristo Singson III, representing his father, Governor Jeremias “Jerry” Singson; Vice Governor Ryan Luis Singson (son of former governor Luis “Chavit” Singson); and other provincial officials.

The Facebook page of the provincial government of Ilocos Sur posted the next day about the groundbreaking ceremony but did not explain why a monument to Marcos was being built in San Esteban.

A social media report offers a sketchy justification for the monument’s erection: “A monument of former president, Major Ferdinand E. Marcos will be erected here, Apatot San Esteban Ilocos Sur.The area was the landing site of a submarine [USS Gar] carrying armaments for USAFIP-NL [United States Army Forces in the Philippines-Northern Luzon] during World War 2 that led to the downfall of Gen Tomoyoki Yamashita in Bessang Pass.”

There were two banners that stressed the significance of the occasion. One connected the building of the Marcos monument to the rehabilitation and improvement of the USS Gar landing site.

The other banner welcomed Sen. Maria Imelda Josefa “Imee” R. Marcos along with Gov. Jerry Singson, Cong. Kristine Singson-Meehan, former Gov. Chavit Singson, and Candon City Mayor Eric Singson. Sen. Marcos did not attend the groundbreaking ceremony.

Another marker of USS Gar landing in Santiago Cove

Forty years ago, on December 27, 1982, then president Ferdinand E. Marcos himself, with First Lady Imelda Romualdez Marcos, led the dedication of a marble marker from the National Historical Institute (NHI) (now the National Historical Commission of the Philippines, or NHCP) to commemorate the landing in San Esteban of USS Gar. That marker was destroyed in a typhoon in 2001. A new one was put in its place, fronting a replica in concrete of the USS Gar. The new Marcos monument will be built beside the marker and the Gar replica.

Rendered in all caps, the text of the present marker, which almost perfectly reiterates that of the older one, reads:

Twice surfacing at Santiago Cove on November 21, 1944, the USS Gar landed on this beach commandoes of the Army of the United States with equipment, arms, ammunitions and supplies led by Captains William Vaughn and William Farell were Lts. Fred Behan and Donald Jamison with two other Americans and Larry Guzman with other Filipinos of the First Filipino regiment. The landing was effected by USAFIP, NL under Col. Russell W. Volckmann with other paramilitary and guerilla units by order of Volckmann, Jamison and Maj. Ferdinand E. Marcos sneaked through the cordon of Gen. Tomoyuki Yamashita to an air strip in Isabela and flew to Camp Spencer.

Besides using numerals instead of spelled-out numbers in two instances, the previous marker clearly placed a period between “supplies” and “led” and one between “guerrilla units” and “by order of Volckmann,” avoiding the current run-on sentences. But evidence shows that the text has bigger problems than the grammatical variety.

The 1982 NHI marker on the landing of USS Gar in San Esteban, Ilocos Sur bears significant errors that should put in question why the marker is in San Esteban in the first place. It is also laced with a lie traceable to Marcos that vested in himself a certain wartime exploit that vaguely connected him to the submarine landing but is categorically unsupported by any factual and historical evidence.

Adding doubt to the 1982 marker is the existence of another historical marker commemorating the Gar landing where it actually happened, in Santiago Cove, Sabangan, Santiago, Ilocos Sur.

Submarine bearing supplies for resistance forces

In mid-1944, as the United States-led Allied Forces made its way from Australia and the southwest Pacific islands to reconquer the Philippines from the forces of the Japanese empire, efforts were made to communicate, consolidate, and supply the guerilla resistance forces in Northern Philippines, or specifically the United States Army Forces in the Philippines-Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL), then under the command of Col. Russell W. Volckmann.

Patricia Murphy Minch, whose father, Col. Arthur Philip Murphy served as Volckmann’s chief of staff and intelligence officer, wrote in the The Luckiest Guerilla, a biography of her father, that a rumor about a submarine bearing supplies for resistance forces in Luzon was received by her father with “far greater significance” than the news on the radio of US forces’ impressive victories as it fought its way back to the Philippines.

In Volckmann’s view, as expressed in his wartime biography, American Guerilla, by Mike Guardia, “Resupply meant relief from chronic shortages that had plagued them since Bataan. If the supply train remained unbroken from now until the Allied invasion of Luzon, Volckmann and his men would no longer have to rely on scavenging from the Japanese or continue borrowing from the local civilians.”

On August 27, 1944, the USS Stingray (SS-186) that departed from Australia on August 16 reached Caunayan Bay, Bangui Bay, Pagudpud, Ilocos Norte under hostile conditions. As noted by the Naval History and Heritage Command of the US Navy, despite the odds, “Special mission successfully accomplished 27 August 1944 after undergoing depth charge attacks and being lightly worked over while reconnoitering designated spot. Landed all personnel and 60% of supplies. Forced to depart after 24 assorted Jap armed sea trucks passed spot.”

Lt. Jose Valera led the fifteen-man radio and demolitions team that came from USS Stingray. But it was not until November 19, 1944 that Valera and his team were able to contact Volckmann’s headquarter in Benguet.

An NHCP marker of the Stingray landing, sponsored by the Philippine Veterans Bank, was installed at the landing site in 2018.

After USS Stingray’s landing, another submarine was supposed to deliver supplies to the USAFIP-NL by September 1944. This did not happen. Years later, Volckmann would learn that the submarine that was supposed to do the supply run was sunk by the US’s own Air Force.

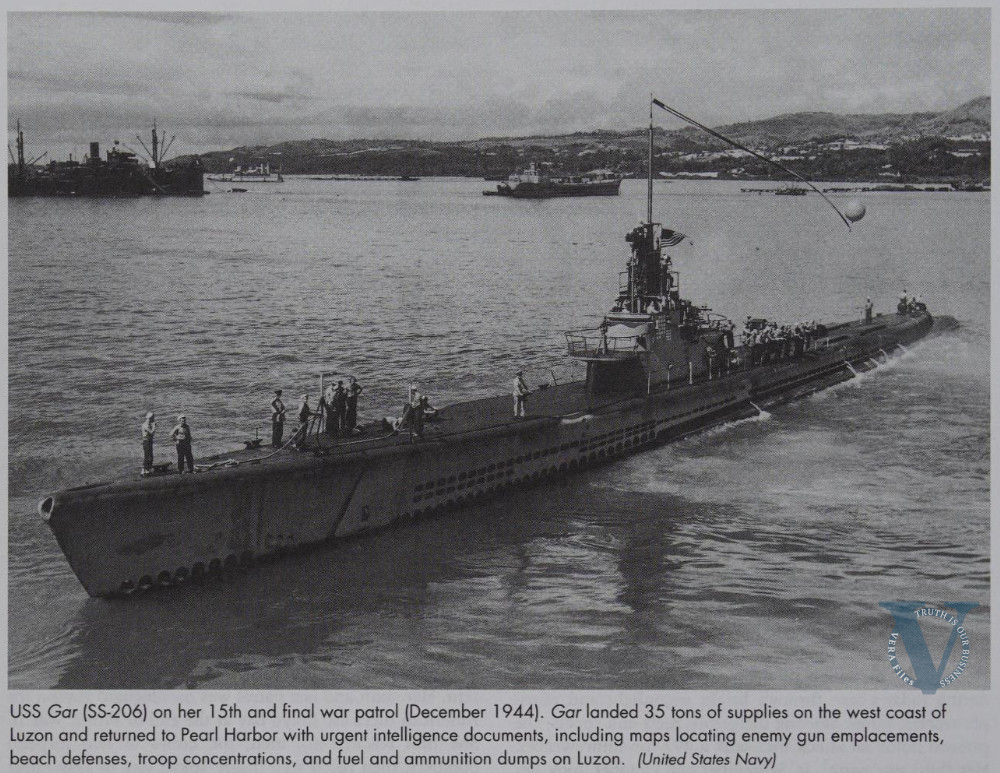

Another attempt was made in October 1944. It was again a failure. Then came the USS Gar (SS-206), the second submarine to venture along the Ilocos coast to deliver supplies to the USAFIP-NL headed by Volckmann.

The 1982 NHI marker at Apatot, San Esteban states that the USS Gar twice surfaced at Santiago Cove on November 21, 1944. The date in the marker is off by one day. USS Gar’s “Report of War Patrol Number Fourteen” dated November 30, 1944 states that its journey to the Ilocos coast started on November 13, 1944 at Mios Woendi Lagoon (part of the Schouten Islands of Papua province, Indonesia), then a forward base of the US Navy.

When it left Mios Woendi Lagoon, USS Gar had a load of “16 army personnel, 4 officers and 12 men, and 30 tons of material” with “Captain W.D. Vaughan, 0-23978, USA in charge of party.”

On November 20, 1944 it delivered supplies to resistance fighters in Mindoro, its first mission. At 5:16 a.m., November 22, 1944, USS Gar’s log reads, “Submerged off Darigayos River, the spot designated for second mission, and commenced closing the beach.”

The log was no doubt correct on the time and date it recorded, but it was mistaken about where USS Gar actually was. And it was this error that would explain why it had to surface twice in Santiago Cove, a place that is definitely not in San Esteban, Ilocos Sur nor was it Darigayos Cove in Luna, La Union.

The precise coordinates of USS Gar’s location was 17°17’02.0″N 120°24’05.0″E (this is a current rendering of the original recorded coordinates 17-17.2N, 120-24.5E). This record is at the “Submarine Activities Connected with Guerrilla Organizations” made available online by the Naval History and Heritage Command of the US Navy. The coordinates situate the USS Gar fronting the Santiago Cove at Sabangan, Santiago, Ilocos Sur.

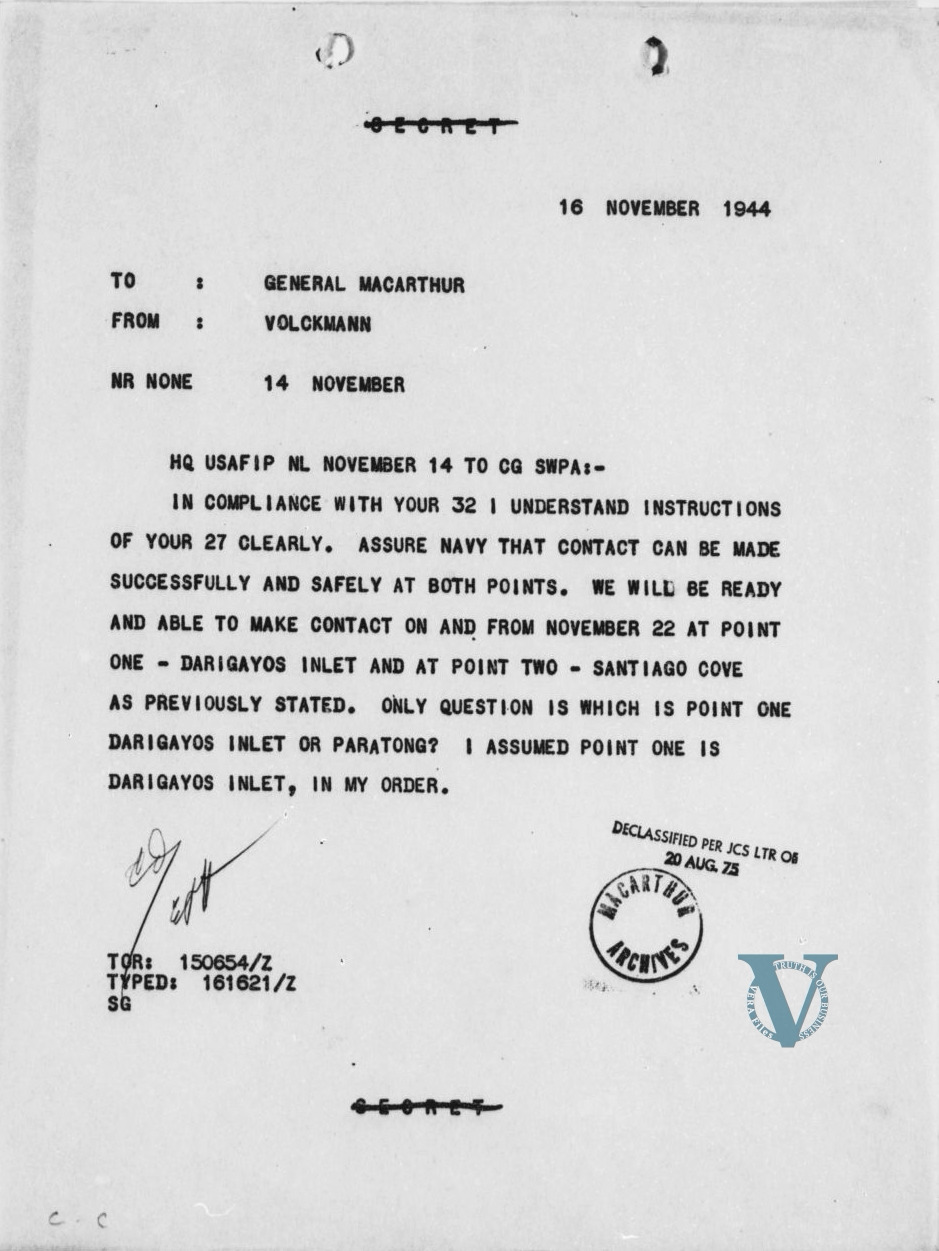

In the failed October 1944 supply run, Volckmann had communicated to the South West Pacific Area (SWPA) command in Australia two submarine landing sites. On November 11, 1944, SWPA asked Volckmann if the same rendezvous points could be used. Volckmann, in his November 16, 1944 reply said yes. “Assure Navy that contact can be made successfully and safely at both points. Will be ready and able to make contact on and from November 22 at Point One – Darigayos Inlet and at Point Two – Santiago Cove as previously stated.”

Volckmann headed the group that waited for the USS Gar in Darigayos, while in Santiago Cove, the group was headed by Maj. George M. Barnett, sub-commander of USAFIP-NL’s second district (the provinces of La Union and southern Ilocos Sur).

It was Barnett’s group that made contact with USS Gar at 6:00 p.m., November 22, 1944. Still thinking that they were at Darigayos Cove, they asked Bartnett if he was Volckmann. Barnett told them he was not, and that they were at the secondary site.

USS Gar’s war patrol report admitted plainly the error in their navigation. “We were amazed to learn that we were at our alternate spot. (Santiago Cove) Later developments proved that we were extremely fortunate to have contacted this party first.”

“Due to the scarcity of men and boats Barnett cannot unload us tonight, however Major Volkman [sic] down at the primary spot was thought to have sufficient men and boats to take care of us. He also thought that Volkman had some intelligence information which he wanted us to take back.” The log continued: “In hopes of completing the mission as soon as possible it was decided to take Major Barnett and four body guards aboard and proceed to the primary spot to contact and unload with Major Volkman.”

Before departing for Darigayos on November 22, Barnett informed them that “there were three small Jap patrol boats 4 miles to the north . . . at San Esteban which patrol 200 yards off the reef parallel to the coast.” Further proof that in the accounts of those involved first-hand in the landing, they were not in San Esteban.

At 9:00 p.m., Gar was at Darigayos. A party led by Barnett was made to land to look for Volckmann’s group. They were not there. Instead, there were Japanese patrols in the area.

“Spot One compromised completely by the enemy,” Volckmann warned the SWPA command on November 22, 1944. “Request that Spot Two be used.”

Gar went back to Santiago Cove at 1:00 a.m., November 23, 1944. The submarine remained submerged about 900 meters from the mouth of the Santiago Cove as it waited for nighttime to unload its cargo and passengers. At 5:55 p.m. Gar surfaced and moved closer to the cove. Barnett was already at hand, ready to start unloading.

USS Gar landed in Santiago Cove

In the “Calendar of Submarine Shipments to the Philippines” from the US Navy Operational Archives in Washington, DC, it is recorded that on November 23, 1944, the Gar under Lieutenant Commander Maurice “Duke” Ferrara, in “Santiago Cove, Wcoast Luzon landed 16 men and 25 tons of supplies; picked up docs [Roscoe 518].”

The following were the men who came with USS Gar: Capt FH Behan, Capt DV Jamison, T/Sgt LO Guzman, S/Sgt CB Maplia, Cpl LC Clemente, Cpl F Bermudes, S/Sgt A Villanueva, Sgt MQ Arellano, Sgt BC Alvez, Cpl Demetrio G Madrano, Cpl AA Pabros, Sgt WH Lowe, S/Sgt AB de la Pena, Capt WA Farrell, Sgt JC Bierley, Capt WD Vaughn.

By 10:00 p.m., the unloading was completed; Gar’s second mission was accomplished.

“The news of the successful submarine contact,” Volckman wrote in We Remained, “and the positive proof of it in the form of equipment from the outside . . . was a stimulus to civilians and guerillas alike. Almost overnight new spirit and greater determination were evident everywhere.”

“U.S. Submarine War Patrol Reports, 1941-1945,” War Patrol No.: Fourteenth/Fifteenth, November-December 1944. From the US National Archives.

In the logs of the Gar’s fifteenth and final war patrol in December 1944, wherein the submarine again brought cargo for USAFIP-NL, this time in Darigayos, and picked up “valuable intelligence information and documents” again in Santiago Cove, they noted that the latter mission was challenging partly because “[from] our previous mission there we know that the Japs had four small patrol vessels at San Esteban, 4 miles to the north of Santiago Cove, whose purpose was to prevent landings such as these.” It was even noted in their December 12, 1944 log that a small ship about five miles away could be seen while they were in Santiago Cove, and that it was “believed to be one of the patrol boats from San Esteban.” Certain that they were sighted, Ferrara, the submarine commander, stated that “Santiago Cove must now be considered completely compromised for missions of this nature.”

Among the sources that claim that the landing did occur in San Esteban is the “After-Battle Report: United States Army Forces in the Philippines, North Luzon Operations,” submitted by Volckmann to the Commanding General of the Army Forces Western Pacific on November 10, 1945, and the book Guerrilla Days in Northern Luzon, published by the USAFIP-NL in July 1946. The latter in fact first calls the alternative landing site as “San Sebastian, Ilocos Sur.”

The claim that the landing happened in San Esteban appears to be an error committed by Col. Volckmann; comparing Volckmann’s and the 1946 USAFIP-NL’s accounts with the Gar logs and the Seventh Fleet Intelligence Center memorandum, Volckmann also erred in the weight of the cargo carried by the Gar for USAFIP-NL (it was 30, not 20). Both the After-Battle Report and Guerrilla Days also misspell Vaughan as Vaughn, suggesting that the San Esteban marker relied mainly on erroneous Volckmann-authored or Volckmann-derived sources (including Volckmann’s earlier autobiography We Remained: Three Years Behind Enemy Lines in the Philippines, published in the US in 1954).

A correction of sorts can be found in Murphy’s biography, which describes the November 1944 landing, but makes clear that it happened in Santiago Cove. And as mentioned above, records of Volckmann’s communication with SWPA clearly indicate Santiago Cove.

No direct link between Marcos and the USS Gar

In pro-Marcos propaganda about Ferdinand Sr.’s war-time exploits, there is no direct link between Marcos and the USS Gar, save in one instance. In his commissioned autobiography, For Every Tear a Victory: Marcos of the Philippines (1964), written by American Hartzell Spence, there is a line in the book’s second chapter implying that Marcos was physically present in Ilocos Sur during the November landing: “Late in 1944 Marcos. . . made contact on a storm-swept beach one night with a United States submarine, which landed a demolition expert, Captain Jamieson, and supplies with which Marcos’ command was to blow up the mountain roads and impede the Japanese withdrawal north of Manila.” This line was reproduced in subsequent (1969, 1979) editions of the biography. The “Captain Jamieson” mentioned almost certainly refers to Donald V. Jamison, unquestionably one of the Gar commandos.

But For Every Tear contradicts itself more than half a dozen chapters later, firmly placing Marcos in Pangasinan during the November landing. This is corroborated by both pro-Marcos and more impartial sources. The very title of the book Ferdinand E. Marcos: 77 Days in Eastern Pangasinan, produced by the Philippine Constabulary Historical Committee in 1982, indicates where, in military-approved narratives, Marcos was between August and early December 1944. The two editions of Marcos: The War Years, co-authored by Cesar T. Mella, who was affiliated with the government think-tank called the President’s Center for Special Studies, and Gracianus R. Reyes, reassert that from Bulacan, aboard a “charcoal-fed chevy car” in September 1944, he proceeded to “Urdaneta. . . thence to Asingan, thence to Tayug and finally to Natividad,” all in Pangasinan, staying in the last town until December.

According to Murphy’s biography, when Marcos showed up at the 5th District USAFIP-NL camp in Isabela between late November-December 1944, the camp’s commander, Col. Romulo Manriquez, did not know what to do with him, asking Murphy for advice. Marcos had claimed that he “had been sent by General Manuel Roxas to make arrangements to supply arms to the North Luzon guerrillas.”

Marcos was also asking where First Lady Esperanza Osmeña was. On October 30, 1944, ten days after then Commonwealth President Sergio Osmeña landed with Gen. Douglas MacArthur in Leyte, on the first lady’s insistence—fearing that they would be taken hostage to Japan— Volckmann’s command rescued her and her family from Baguio. Until they rejoined President Osmeña in Dagupan in January 1945, their whereabouts must be kept a secret.

Murphy assumed Marcos was a spy and suggested a means of eliminating him. Marcos was purportedly saved by the intervention of USAFIP-NL’s G-3 (Army Operations), Col. Calixto Duque, who was familiar with Marcos’s family. Volckmann reversed Murphy’s order to eliminate Marcos, and Murphy ordered Manriquez to allow Marcos’s attachment to the 14th Infantry, but only if he was “kept under close watch.” Another version of this story, though much less flattering to Murphy, is told in For Every Tear.

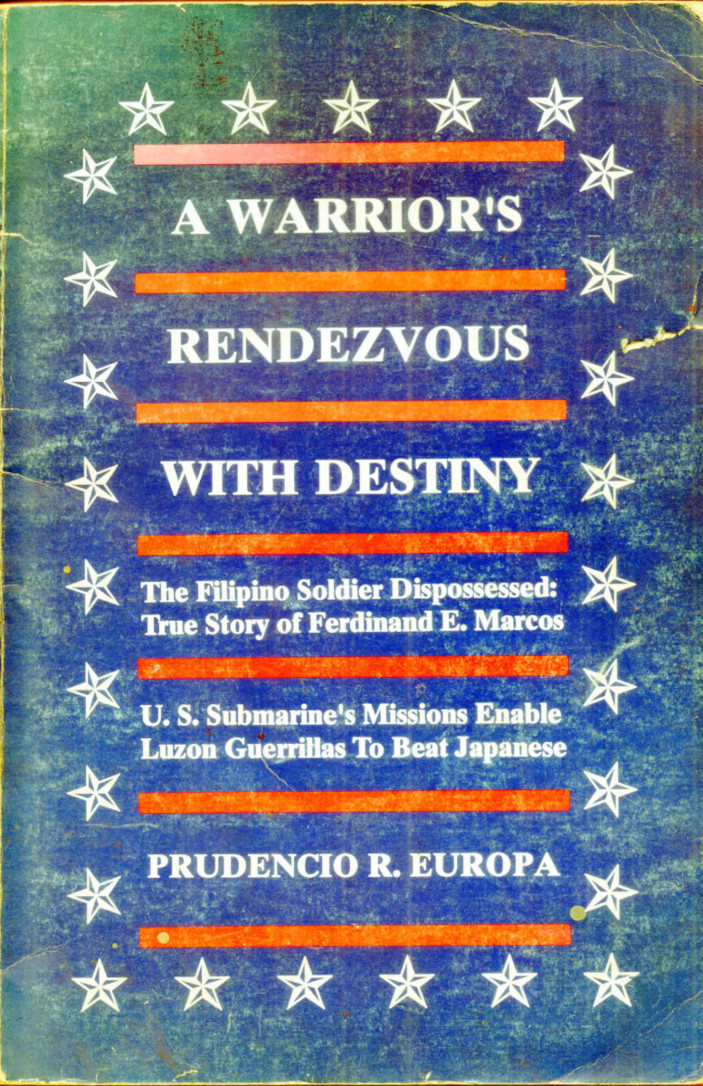

Besides For Every Tear, the most prominent book linking Marcos with the USS Gar—and only tenuously, to be very charitable—is a book by Prudencio R. Europa with the kilometric title, A Warrior’s Rendezvous with Destiny: The Filipino Soldier Dispossessed: True Story of Ferdinand E. Marcos; U.S. Submarine’s Missions Enable Luzon Guerrillas to Beat Japanese. The book was published in September 1989, shortly before Marcos’s death. Europa was, according to the book’s brief biographical note, a “newspaperman from the Deep North”—born in San Esteban, Ilocos Sur in fact—who had “followed the Marcos career” since Marcos first term in Congress (1949-1951), becoming Press Counsellor of the Embassy of the Philippines in the US in 1983.

Based on the acknowledgements section of Europa’s book, what he really wanted to write initially was an account solely about the purported landing of the Gar in his hometown, but it was “[the] ill-treatment of the Filipino Soldier and the martyrdom of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos” [that] spurred [him] to go into publication.” The result is a volume (more than half of which is appendixes and pictures) that, as its title suggests, is partly a defense of Ferdinand Marcos’s war record, and partly an unconnected narrative about the Gar.

Europa listed among his sources, besides Jamison and another Gar commando, “elders of Barrio Apatot in San Esteban” who “gave recollections of that submarine landing.” He also evidently read and discussed the contents of the Gar’s fourteenth and fifteenth war patrol reports, quoting from them verbatim. Importantly, however, he misrepresented them by claiming these archival sources state that the November landing and unloading happened in San Esteban, not Santiago Cove. Nor does he state that based on those war patrol accounts, San Esteban was actually highlighted as a place to avoid for submarine landings.

Others who had read these records were more honest. In citing the logs of the Gar‘s fourteenth war patrol, Generoso Salazar, Fernando Reyes, and Leonardo Nuval, in their 1992 book World War II in North Luzon, Philippines, 1941-1945, make clear that the Gar surfaced off of Santiago Cove in November 1944.

Europa claimed that those who disembarked from the Gar in the evening of November 23, 1944 were met by members of the Women’s Auxiliary Service of the 121st Infantry. Though he does not name a source for this, it does affirm that only members of the 121st Infantry, which Marcos was never a part of, met with the Gar’s passengers. Guerrilla Days further affirms this, stating that “[the] 121st Infantry was instrumental in making contact with the submarine that landed arms, ammunitions and supplies for USAFIP, NL in November of 1944, and in bringing them to GHQ [General Headquarters], USAFIP, NL.” Guerrilla Days further states that in all of the submarine landings in November-December 1944 (the Gar made another landing, this time in Darigayos, La Union, in early December 1944), “the men of the 121st Infantry played an important part,” being the ones who “carried the supplies up mountain trails to General Headquarters of the USAFIP, NL for proper distribution to the field.”

The only time Europa mentioned Marcos as being connected to the Gar was when the president attended the San Esteban marker’s inauguration in December 1982.

Moreover, neither Marcos nor Jamison mentions the former’s presence during the November landing in other statements that they authored. Marcos does not mention it in “Ang Mga Maharlika – Its History in Brief,” one of the documents he submitted to the United States Army when he was attempting (unsuccessfully) to have the fictitious exploits of his Ang Mga Maharlika guerrilla unit recognized. Jamison, in an affidavit executed in Manila on December 31, 1982, claims that he worked closely with Marcos only while the former was attached to the 14th Infantry, specifically between January and March 1945.

Even the service record of Marcos, issued by the GHQ of the Armed Forces of the Philippines on March 4, 1996, which is included in the decidedly pro-Marcos document compilation titled Let the Marcos Truth Prevail, states that Marcos only attained the rank of major when he became affiliated with the 14th Infantry on December 12, 1944, after the Gar landings. Not a shred of credible evidence places a Major Ferdinand Marcos under the command of Volckmann before December 1944.

What then accounts for the last line of the San Esteban marker (“By order of Volckmann, Jamison and Maj. Ferdinand E. Marcos sneaked through the cordon of Gen. Tomoyuki Yamashita to an air strip in Isabela and flew to Camp Spencer”)? After thoroughly going through related pro-Marcos propaganda, it becomes clear that that line is based on a story popularized by For Every Tear that has nothing to do with the landing. Reading the marker alone, one would think that immediately after the November 1944 landing, Marcos guided Jamison through enemy territory to Camp Spencer. But Spence says this perilous trek occurred in April 1945, when both Marcos and Jamison were attached to the 14th Infantry of USAFIP-NL.

All-out propaganda

Why did the NHI deem it necessary to mention Marcos in the “San Esteban Landing” marker, if his only “connection” was an excursion with one of the Gar’s passengers several months after the landing? Some context may be helpful. In December 1982, opposition newspaper We Forum was shut down and its publisher-editor, Jose Burgos, was arrested. The paper was charged with subversion, or “conspiracy to overthrow the government through black political propaganda, agitation and advocacy of violence” because it purportedly wanted to “discredit, insult and ridicule the president to such an extent that it would inspire his assassination,” as evidenced by its publication in November 1982 of a series of articles by Bonifacio Gillego that debunked several claims about Marcos’s wartime heroism. For the same series of articles, Burgos was charged by Marcos-allied veterans with libel, not on behalf of Marcos specifically, but of all soldiers of the Philippines. Jamison’s affidavit was executed in support of Marcos’s wartime record; he testified during the preliminary investigation for the libel case in January 1983 (that case did not go beyond the PI, while the subversion case was eventually dismissed). Presumably, the historical marker, inaugurated by Marcos shortly after We Forum’s office was raided and padlocked, and a little over a week after Burgos was released on house arrest, was also connected to this propaganda effort.

Another Gar passenger who executed an affidavit in December 1982 in favor of Marcos was Larry O. Guzman, an American citizen who was born in San Esteban. Guzman’s affidavit, also included in Europa’s book, hews very closely to Jamison’s, and affirms that they met Marcos only when they were all together with the 14th Infantry, well after the landing.

Jamison and Guzman, along with USS Gar commander Ferrara and another commando, Maj. Fred Behan, were conferred “the nation’s most distinguished military awards” by Marcos on January 4, 1983, a few days after the San Esteban marker inauguration. Marcos had also conferred at least three awards to his friends Jamison and Guzman since the former became president (a February 1984 article in The Filipino American states that these were “the Gold Cross Medal, distinguished Conduct Star, and Outstanding Award Medal.”).

Though Jamison’s and Guzman’s role in helping to hasten the defeat of the occupying Japanese forces are unquestionable, their claims about their comrade Marcos deserve scrutiny. In their affidavits, Jamison and Guzman assert that Marcos was always consulted on intelligence and combat ops, and even led demolition missions and heroically engaged enemy combatants. Official records of the 14th Infantry, USAFIP-NL, show that Marcos was designated regimental S-5, or civil affairs officer, at the time of the 1945 combat engagements involving Marcos that Jamison and Guzman supposedly witnessed. A compilation of 14th Infantry correspondences among the Philippine Archives Collection of the US National Archives shows the kind of work Marcos actually did at that time; the subject of the letter, dated February 8, 1945, was “Property Damaged, Burnt or Destroyed,” and it was a comment on a fragmentary report, not based on his own observations. Another letter, by a Captain Juan. Ma. Sabalburo of the 14th Infantry, dated 15 January 1945, talks about the letter writer’s trial (presumably a court martial), which is being handled by a Lt. Manaois and Major Ferdinand Marcos.

In one reconstructed roster of the 14th Infantry, which is among the documents submitted for the unit’s recognition by the US Army, Marcos is listed as a major who became a member of the unit on December 12, 1944, and toward the war’s end was assigned to the unit’s headquarters. In Guerrilla Days, an appended station list includes Major Marcos (misspelled “Farcos, Ferdinand”), assigned to serve as Assistant Adjutant General, which meant that he was principally an administrative officer. This is further affirmed in Col. Murphy’s biography, wherein Marcos is described as having served as a “civil affairs officer,” attached to headquarters until the war concluded. Finally, one of Gillego’s We Forum articles—which cites information from sources such as Capt. Vicente Rivera, staff and line officer of the 14th Infantry—mentions that by May to June 1945, Marcos was “in the relative safety of USAFIP, NL headquarters,” away from the Battle of Bessang Pass, which he allegedly participated in.

A book of lies

To reiterate: there is no link between Marcos and the landing of the USS Gar in Ilocos Sur in November 1944, besides an outright lie and a claim of an adventure with one of the Gar commandos, which is contrary to official records and communications, both of which are found in a notoriously unreliable and self-contradicting source: Spence’s For Every Tear a Victory.

For Every Tear starts with a falsehood: “Ferdinand Edralin Marcos was in such a hurry to be born that his father, who was only eighteen years old himself, had to act as midwife.” Mariano Marcos was several months over twenty years old when Ferdinand Sr. was born.

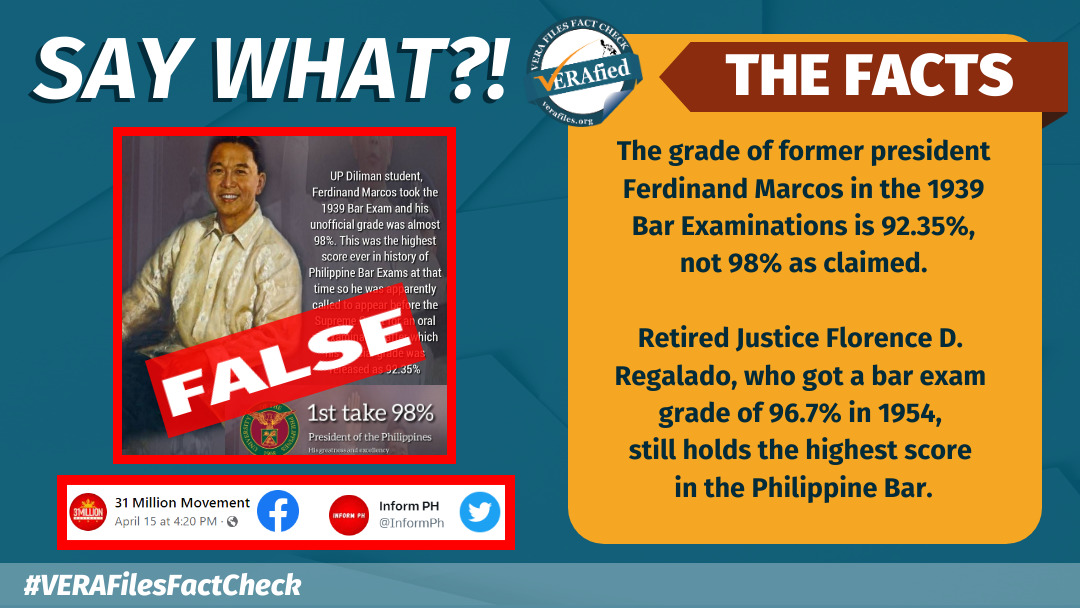

Besides false stories about Marcos’s wartime activities, the book is also responsible for propagating the lie that Marcos had the highest bar exam result in history, but had his score reduced by the bar examiners.

Moreover, the most authoritative sources on the matter show that there should not even be a marker on the November Gar landing in San Esteban, let alone one that unnecessarily mentions Marcos. Curiously, the online National Registry of Historic Sites and Structures of the Philippines does not include the San Esteban Landing marker, either among still existing sites and structures or those that had been delisted or otherwise removed. Given the evidence presented here, NHCP may intervene, invoking one of the mandates of the Commission stated in Republic Act no. 10086: “actively [engaging] in the settlement or resolution of controversies or issues relative to historical personages, places, dates and events.”

Even the Department of Tourism can take an interest in the matter, given that because of Republic Act no. 11408, Santiago Cove is officially a “tourist destination”; as such, its “development shall be prioritized” by the DOT. Emphasizing the place of Santiago Cove in the liberation of the Philippines would likely help boost tourism there. Consider that there is already a marker to the landing in Santiago Cove, though one without the NHI/NCHP’s imprimatur.

Devoid of historical basis, the monument is an addition to a growing list of permanent memorialization of Ferdinand Marcos Sr. unveiled after his remains were reinterred at the Libingan ng mga Bayani in 2016. The list includes the NHCP historical marker placed in 2017 under a repositioned statue in Batac, Ilocos Norte; a bronze statue of Marcos erected in Banna, Ilocos Norte sometime in 2019; a statue of Marcos in Paniqui, Tarlac, which was installed in August 2019; and new commemorative marker at the Pantabangan Dam in Nueva Ecija, which features a huge portrait of Marcos.

(Miguel Paolo P. Reyes and Joel F. Ariate Jr. are researchers at the Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines Diliman. Professor emeritus Ricardo T. Jose of the UP Department of History provided helpful insights and some of the sources used for this article. Ariate, Reyes, and Larah Vinda Del Mundo are the authors of the recently released book, Marcos Lies, which contains chapters discussing other false claims about Ferdinand Marcos’s wartime record. Buy the book here.)