Often, as internal oppression intensifies, the closer and more scathing external scrutiny becomes. In response, the authority being made accountable calibrates its response as the crisis deepens: from outright denial to obfuscation to censorship and to an eventual crackdown on its critics.

On June 4, 2020, the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) released its comprehensive report on the Philippines. “The long-standing overemphasis on public order and national security at the expense of human rights has become more acute in recent years, and there are concerns that the vilification of dissent is being increasingly institutionalized and normalized in ways that will be very difficult to reverse,” it said.

The report added that “in just the first four months of 2020, including during the COVID-19 pandemic, OHCHR documented killings of drug suspects and human rights defenders. Charges were filed against political opponents and NGO workers, including for sedition and perjury. A major media network was forced to stop broadcasting after being singled out by the authorities. Red-tagging and incitement to violence have been rife, online and offline.” It said while measures were taken to mitigate the pandemic’s economic impact on vulnerable communities, “threats of martial law, the use of force by security forces in enforcing quarantines, and the use of laws to stifle criticism have also marked the Government’s response.”

The Office of the Presidential Spokesperson, in a statement on June 6, 2020, took note of the UN agency’s recommendations but rejected its “faulty conclusions.” It said the government will continue to respect its international legal obligations, including human rights.

How or why the OHCHR’s conclusions are faulty, the government offered no explanation. Just an outright denial. A refusal to be made accountable — reminiscent of another time in our history when government’s denial came with both threat and censorship.

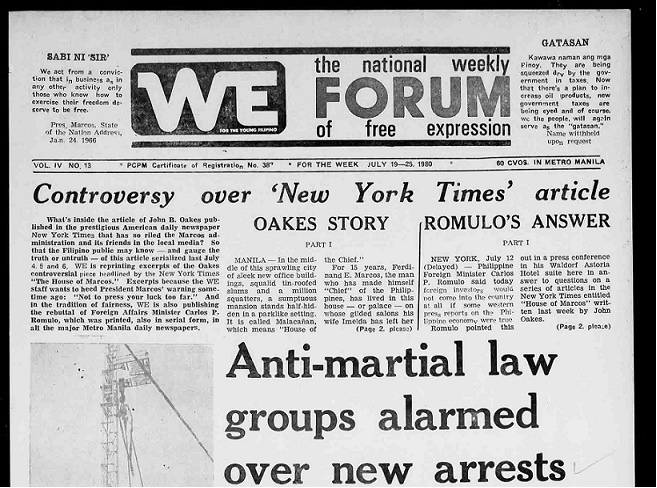

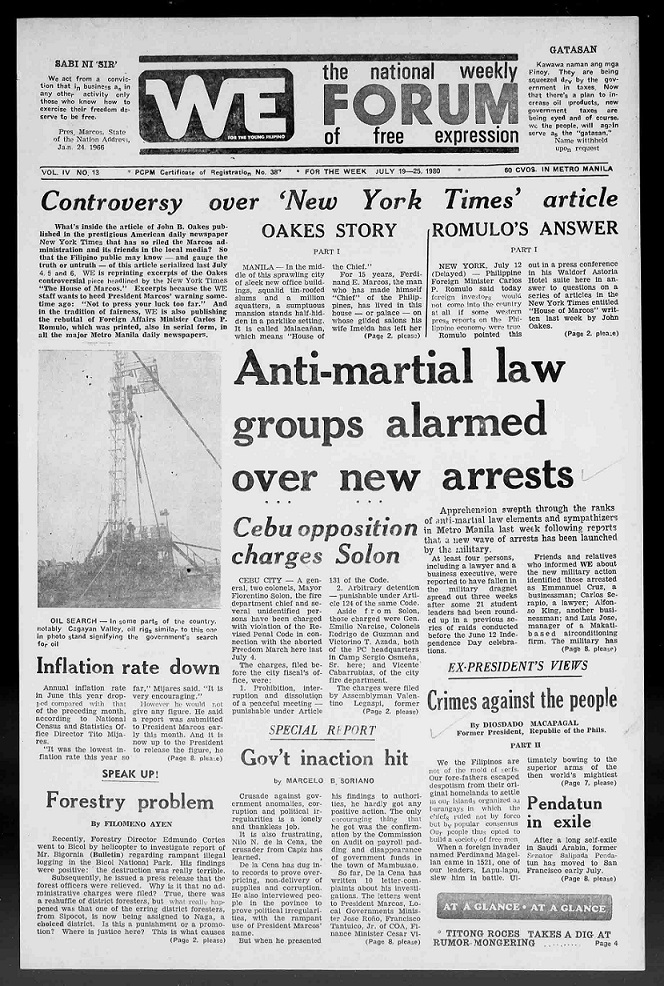

Almost forty years ago today, on July 4 to 6, 1980 the New York Times published a three-part story by John B. Oakes entitled, “The House of Marcos.”

In the local press, the Oakes article appeared only in We Forum, with a significant portion excised. In running the story We Forum heeded then President Marcos’s dire warning to them: “Not to press your luck too far.”

We Forum ran the excerpts from the Oakes story in its July 19, July 26, and August 2, 1980 issues. Side by side with it was the rebuttal from then Minister of Foreign Affairs Carlos P. Romulo, which was carried by all the major newspapers in Metro Manila.

Oakes started his story with these questions: “How much longer will President Marcos be able to retain his grip in Malacanan? How has he managed to do it thus far?”

In July 1980, Marcos was in his fifteenth year in office as president. He was twice elected to the post, totaling eight years. He would have been president only until 1973. Before his second term expired in 1972, he declared martial law and by then, for almost eight years, ruled as a dictator. There seemed to be no end in sight to the martial law that he imposed. And only he could end it.

“The Marcoses have kept their tenancy of Malacanan by subverting the Constitution, suborning the army, corrupting the elections, trampling on civil rights, muzzling the press, squandering the country’s resources, plunging into heavy foreign debt and enriching their family and friends,” Oakes wrote. To be able to pursue all these with impunity, Marcos had to have the United States firmly in his corner.

Here Oakes switched to Marcos’s reputation as a skillful politician. “There is no doubt that Marcos has been skillfully playing ‘the American card.’ He publicly inveighs against possible ‘intervention by the United States in the affairs of the Philippines.’ Yet he managed last year to obtain from the Carter administration a $500 million, five-year commitment in military and economic aid as ‘compensation’ for American use of the huge air and naval bases at Clark Field and Subic Bay.”

The second installment in the Oakes series made a grim portrait of the impoverished Filipinos suffering under the Marcos regime. “Three out of five Filipino children, according to the government’s own figures, are malnourished—partly because their parents are ignorant of proper nutrition but also because they are ‘economically restrained’ from buying nutritious foods.’”.

The latter third in the second installment of Oakes’s piece was not published by the We Forum. It was on the First Lady Imelda Romualdez Marcos, who on July 2 that year, just celebrated her 54th birthday. Birthdays then of the conjugal dictator were celebrated as days of public thanksgiving. Oakes excoriating Imelda during her birthday week would not have suited her well.

In addition to the “Bliss” projects, the first lady has instituted a system of subsidized food shops, where some basic necessities can be purchased at heavily discounted prices. But such socially useful innovations tend to be obscured in the public mind by the enrichment of her family and friends, and also by her style of extravagant spending and display, which she is convinced the Filipino people need, admire and want to emulate. “I think of myself as the star and the flame,” she says, “to inspire the people and move them to progress.”

Once, when asked why so many of her entourage had become so wealthy and powerful since Marcos’s imposition of martial law, the first lady was reported to have replied: “Some are smarter than others.”

That’s the sardonic title of an impressively documented underground pamphlet now circulating in Manila. It was written by “a group of concerned businessmen and professional managers.” It lists, with names and details, some of the principal beneficiaries of the “new society” along with the scores of major corporations and business institutions in which they have an important voice or outright control.

At least half a dozen members of the Marcos family, several high officials, including a general, and more than a dozen newly rich friends and close associates are among those “smarter than others”, with wealth and influence to show for it.

The last of the installments asked whether Marcos will go the way of the deposed Shah of Iran. “Like the shah, he and his consort pursue an ostentatiously luxurious style of life, as do their families and friends—while an estimated 40 percent of their people live in extreme poverty, some approaching the starvation level.”

For Oakes, Marcos was then sitting atop a rumbling social volcano. Marcos only managed to keep himself on top and contain the opposition through “cases of arrest without warrant, imprisonment without charge, torture without mercy, murder without cause.”

Oakes’s story for the New York Times was syndicated in various newspapers outside of the Philippines.

On July 12, 1980, then Minister of Foreign Affairs, Carlos P. Romulo held a press conference in his Waldorf Astoria Hotel suite in New York to refute Oakes’ assertions. He turned the transcript of his question-and-answer session into a six-question primer distributed to the media. As mentioned, all newspapers of note in the country published it.

Is the Marcos regime repressive?

“Authoritarian, yes; repressive, no.” Romulo denied that there was widespread trampling of civil rights. If civil rights were “in varying degrees regulated and limits set to their free exercise,” it was “in accordance with the imperatives of public order, community welfare, and the values of society.” Romulo continued, “The government is ‘authoritarian’ in the sense that the President exercises the strongest executive powers. There is greater central planning especially of social economic development. But there is also greater participation of people in the political process, and more regional and local autonomy. In effect, a balance has been achieved between individual rights and the demands of law or of authority. Where before there was license and even anarchy: to this extent it is ‘authoritarian’.”

Is there rising opposition to the Marcos regime?

The notion of a rising opposition, Romulo said, was merely “based on the superficial observations of hurried visitors to Manila, or on armchair speculations in some New York office.” In turn, this amusing observation came from elements who were at “the fringes of Philippine society”: “long-term opponents of President Marcos, habitual critics of government, impractical idealists, or the disaffected.”

How has President Marcos maintained his position of leadership?

“Contrary to gossip, speculation, and highly biased judgment of some foreign observers, President Marcos remains as titular, factual, and effective head of the Philippine government and leader of the Filipino people, by legislative fiat, by direct expression of the will of the people through various referendums, and by the undeniable fact that he is best suited to lead his people out of their age-old problems and into new life of greater opportunity and prosperity for all…,” Romulo said. “As President Marcos himself says, ‘It is simply inconceivable that a people who have gone through a hundred years of struggle for their rights and liberties would tolerate, let alone support, a repressive government’.”

Is American aid serving to prop up the Marcos regime? Is President Marcos “skillfully playing ‘The American Card’”?

Romulo’s retort was if there was an “American Card” and if Marcos was playing it, then he was not doing so skillfully since “the current levels of American economic aid average $75 million per year. For 1980, American military security support assistance will amount to $20 million. . . It is a hyperbole—and perhaps ironic—to say that they represent a ‘skillful’ playing of the American card.”Proceeds from the military bases agreement, Romulo contended, cannot be considered as propping up Marcos since they will be in the form of military assistance from 1980-85, regardless of who was president. What it props up is “the American security arrangements for the entire region as a part of the US global security system.”

Much has been said about endemic poverty in the Philippines, the gap between the rich and the poor is said to be widening, and there is widespread privation, and even starvation. Are these reports true? What are the effects of President Marcos’ policies on the situation?

Romulo conceded that, “There is no starvation, but malnutrition.” But that was only expected because, for Romulo, during those times everybody’s poor and suffering: “Poverty is endemic in most societies today, be they developed or developing, the Philippines is no exception.” The current situation is not Marcos’s fault. “In the case of developing societies, disparities in wealth, property, status and power can be traced to their colonial past.” And how could anyone speak of widening gap between rich and poor and there was hardly any wealth to speak of? “There can be no equalization of wealth if in the first place that wealth does not yet exist, there can be no creation of national wealth if that nation does not enjoy the opportunity to share the world’s production of goods.” But Marcos was doing his best to make things better.

Is it true that President Marcos has plunged the Philippines into heavy foreign debt, and that he squanders Philippine resources?

Romulo claimed that the Philippines’s external public debt until then was much less than that of similarly situated countries, like Mexico or Indonesia. All other economic indicators like the debt service ratio, the in-flow of foreign investments, the country’s international reserves, and the export receipts all point to “a picture of progress, not of stagnation or squandering.”

When the Philippines plunged into a deep political and economic crisis after the assassination of Ninoy Aquino in 1983, all the untruths in Romulo’s response were laid bare.

Besides Romulo, Teodoro Valencia and Gerardo Sicat also took to the Marcos controlled press to impugn the Oakes story. Valencia, known then as the dean of Marcos apologists, wrote in his Daily Express column that Oakes’s article was biased, unfair, and malicious. Sicat, then Marcos’s economic planning minister, quibbled with the statistics that Oakles cited in his piece. Like Romulo’s, his rebuttal was featured in all the metro dailies.

Ernesto Avila, in a letter to the We Forum, pointed out the absurdity of the situation. “Unfortunately, yet quite expectedly, these apologists wrote against an article that the supposed ‘free’ Philippine press never published. Not until your voice-in-the-wilderness of a paper printed the Oakes feature story. We were being asked to damn a foreign newspaperman whose article we were not even allowed to read.”

For all the defenses that the dictator’s men put up, they dare not mention one topic: the excesses of Imelda Marcos. The copy published in the We Forum was sanitized, so they may have thought it prudent not to call attention to the issue.

Forty years later, the Oakes story is available in online digital archives and all the extant We Forum issues at the Rizal Library of the Ateneo de Manila University is accessible online (http://rizal2.lib.admu.edu.ph/weforum/). This minor controversy reminds us that what is often suppressed amidst a threatened press bears the truth.

In April 21, 1980, a couple of months before the New York Times published the Oakes story, Marcos himself spoke before the American Newspaper Publishers Association in Hawaii, maintaining that he “remain[ed] convinced that the American tradition of fair play and giving the other guy a chance to talk still governs.”

But in his book In Search of Alternatives: The Third World in an Age of Crisis, published also in 1980 by his government’s main propaganda arm, the National Media Production Center, Marcos did not hide his annoyance of the foreign press, especially the American ones.

“Western press reports about government failures, tyranny, alleged denial of human rights, poverty, assassination and coup d’etat often stem from a pre-judgment of the societies in which these events occur . . . the Western press hardly reports, discusses or interprets Third World objectives, strategies and programs for development,” he wrote.

In the same April 21 speech in Hawaii, Marcos claimed that though his government was authoritarian, it was not tyrannical, “We have never driven out a correspondent.” But as the Honolulu Star Bulletin observed in the same news report on his speech, “his government refused reentry to Arnold Zeitlin, the Associated Press Manila bureau chief who had written a piece considered critical of the Philippine president.”

In the history of the Marcos regime, the Oakes story is a mere footnote. It was a front-page piece, above the fold story in the We Forum, but it was not the main headline.

Two years later, the dictator had had enough of the We Forum. Marcos’s animosity towards the paper escalated, promising at one point, the Los Angeles Times reported, “that he would make Burgos and his colleagues ‘eat’ the newspaper.”

On charges of “conspiracy to overthrow the government through black political propaganda, agitation and advocacy of violence” because the paper aimed to “discredit, insult and ridicule the president to such an extent that it would inspire his assassination,” the paper was raided and shuttered on December 7, 1982 and its editor-publisher, Jose Burgos Jr. and thirteen others were hauled to jail (there were two more but they were in the United States). Eventually, they were put under house arrest. The trigger for the arrest and closure was a story on the fake Marcos medals written by Bonifacio Gillego. As one Catholic cleric remarked in the Oakes story, “Oh, yes, we have freedom of speech. But what we don’t have is freedom after speech.”

When the We Forum was closed, the January 2, 1983 issue of the Los Angeles Times quoted Teodoro Valencia’s column in the Daily Express: “Newsmen know that constructive dissent and criticism against the government have never provoked such serious reaction from the government. Is freedom the right of any man to say or print whatever he pleases?”

After 774 days, on January 21, 1985, We Forum reopened. In its December 26, 1984 decision (G.R. No. L-64261), the Supreme Court found that the warrants were defective.

For the Supreme Court, “Such closure is in the nature of previous restraint or censorship abhorrent to the freedom of the press guaranteed under the fundamental law, and constitutes a virtual denial of petitioners’ freedom to express themselves in print.”

As authorities today again resort to semantics to mask the brute application of law, We Forum’s saga – from the Oakes story to the fake Marcos medals – is a reminder of machinations of those in power to silence the more critical voices in media.

The soon-to-be law Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020 is characterized by Presidential Spokesperson Harry Roque as tough but not draconian. The conviction of Rappler CEO Maria Ressa and former writer/researcher Reynaldo Santos Jr. for cyberlibel is not an assault on press freedom but an issue of accountability. So says Chief Presidential Legal Counsel Salvador Panelo in his press release. So says Presidential Communications Secretary Martin Andanar in his response to a statement from the US State Department. As if Romulo is still speaking: authoritarian but not repressive. As if Marcos is still around: authoritarian but not tyrannical.

But as before, external scrutiny matters. It forces the administration to go on record. A fragment in our country’s long history of oppression gets written. We are able to relearn this history during these trying times because their struggle left an imprint of courage, however imperfect. And the writing of that history always starts with the likes of Burgos and the We Forum.

Jose Burgos Jr., in his publisher’s note in the resurrected We Forum wrote: “But here we are once again, alive and kicking, ready to continue with the struggle for truth, justice and freedom, to contribute to our modest share to the efforts of all freedom-loving people to dismantle all the devilish instruments of oppression and suppression under which the nation has long suffered.”

Here we are once again, indeed.

(Joel F. Ariate Jr. is a university researcher at the Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines Diliman. Miguel Paolo P. Reyes and Larah Vinda Del Mundo provided research assistance. This piece is part of their Center’s on-going research program, the Marcos Regime Research.)