Children start their reading journey with mythical monsters like Medusa, Scylla and Charybdis, and Cerberus in Greek mythology, or Loki’s fearsome children in Norse mythology (Midgard serpent Jormungundr, goddess of hell Hel, and king of chaos Fenrir Wolf). Then there are Anubis, Horus and Ra — some of the anthropomorphic animal-deities of Egyptian myth.

A Filipino child’s early reading list is completed by the pantheon of Philippine mythological creatures — the aswang, manananggal and tikbalang.

The mythologies help illustrate the monsters’ lack of moral code, explaining their deplorable, even blasphemous, behavior, which, in turn, teach children lessons in righteousness and evil.

That childhood lessons vanish and the monsters in their altered forms remain is a discovery I made in whittling down my tsundoku. The stories of Caroline S. Hau, Ninotchka Rosca, and Katrina Tuvera capture the monsters of today — with varying degrees of hideousness — comfortably ensconced in society.

Ugly love

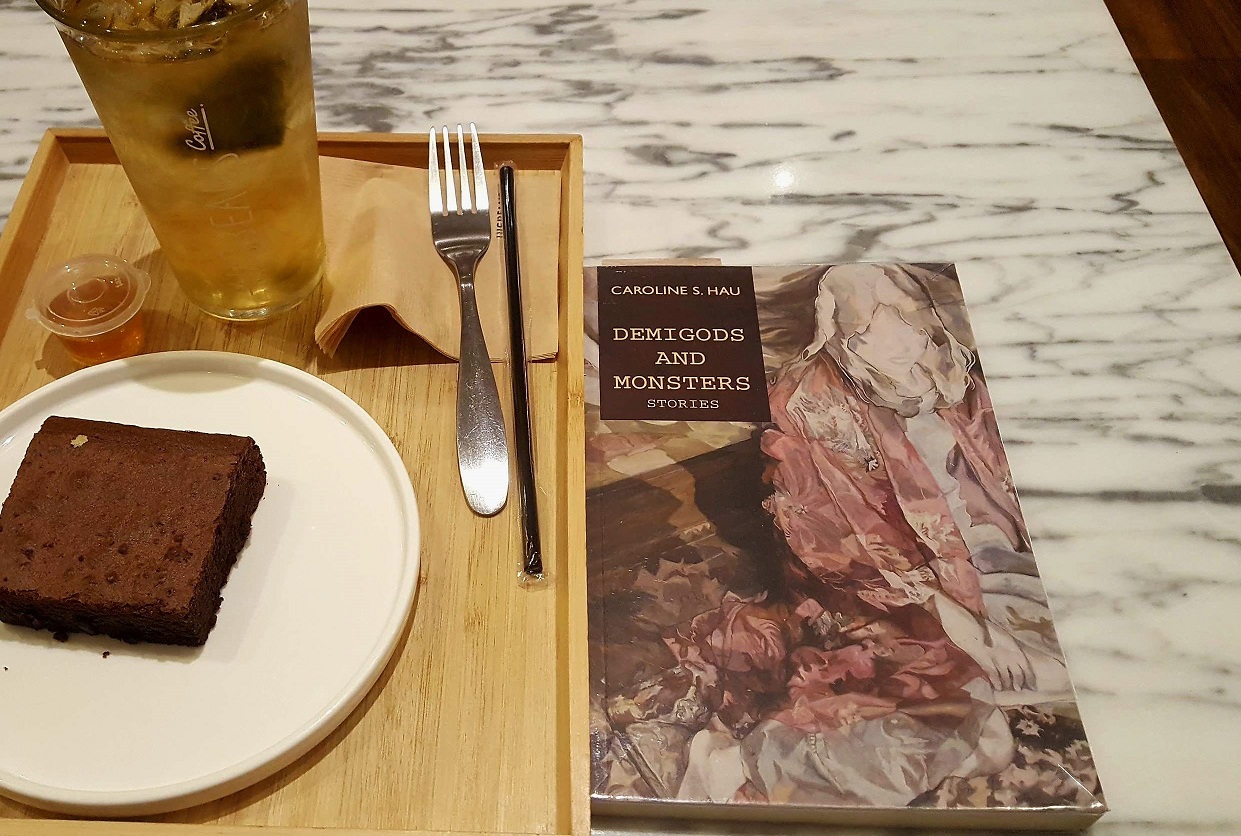

Love turns people in love, wanting love, denied love, or fooled by love into treacherous monsters. They’re in “Demigods and Monsters,” Hau’s collection of short stories (The University of the Philippines Press).

Ellie Chua is reduced to spying on her cheating husband of 21 years in “The Love Hospital.” She’s nettled at being replaced by a younger woman considering she’s the capital and know-how of her and her husband’s thriving supermarket empire. She hires a Xiamen-based agency specializing in extramarital affairs that classify women as one would objects: “second woman,” karaoke bar material who knows her place, and “Little Third,” educated city girl looking for love and marriage.

Using dirty family secrets as arsenal elevates arguments between an estranged couple in “The Girl in the Aqua Dress.” Lia Silayco-Agalon once captivated Singapore’s elite in an aqua Dior crêpe de chine dress. Prior to their divorce, her husband, Alexander Liao, says he’s forgiven her for falling for a gold digger, someone beneath her station. Never mind that he had his own affair and was absent from their marriage for two years — he was discreet, unlike her. They proceed to spew vitriol: The Silaycos are hick traders turned small-time landowners while the Agalons are lobbyists. The Liaos descend from opium farmers and traffickers of firearms, counterfeit currency, coolies, and prostitutes.

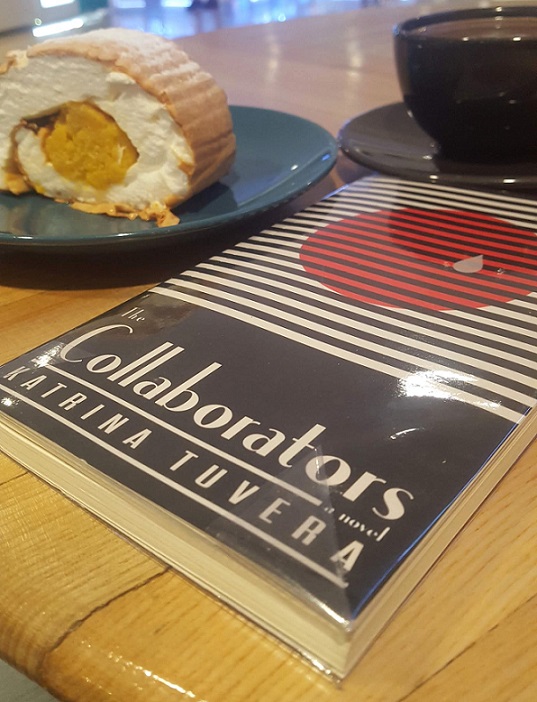

In Tuvera’s novel “The Collabolators” (Bughaw), holders of power change when secrets between husband and wife are discovered. After Carlos Hernando learns that his wife Renata is on contraceptives, he takes horrid measures against the instigator, pharmacy owner Hans Bruckheimer, a naturalized German and Renata’s employer-friend. Livid, Carlos tells Hans to cut ties with Renata and, later, as the final revenge, blackmails Hans, reminding him of being a wartime collaborator.

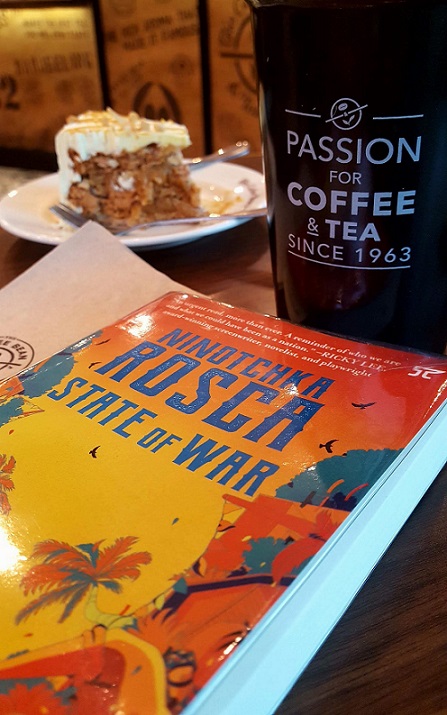

Love turns into sheer hatred in Rosca’s novel “State of War” (Anvil Publishing). Meeting her “late” rebel-husband Manolo accidentally in the jungle, Anna Villaverde learns, as she grieves for him, that his death was staged, he abandoned his comrades underground, informed on them during his capture, and worked for a despotic soldier by making and administering drugs to captured “dissidents” in interrogation. Manolo’s cavalier attitude after she mentions her immense suffering because of him, coupled with his casual admission of her correctness in telling him to remain politically neutral, triggers Anna’s homicidal side: She rams her knife into the back of his head.

Rosca releases an old monster when she rewinds time back to when Spanish friars perverted love. They preached about abstinence yet lusted shamelessly after women — a nubile indio one day, another man’s wife the next.

Monsters galore

Teenaged monsters are arrested in Japan for murder in Hau’s “Child A.” The boys are tagged Child A and Child B by the police. (Child A pushed the victim into a river as payback for having his protectors beat him up, like how it was in his elementary and junior high years when he was taunted for being “half” — as in half-breed — and dragged across the floor. He and Child B burned the victim’s clothes and shoes in the public toilet.) Child A is half Filipino, half Japanese, and has watched his mother endure domestic violence.

Ghostly creatures from an autocratic regime fill Hau’s story “Obituaries.” Teofilo Magdangal is taken from his house in the dead of night and tortured for saying in a town meeting that the forced removal of farmers from their land is a pretext for landgrabbing by big agribusinesses. He survives to tell his story to the Task Force Detainees Philippines that submitted a report in 1984 to the United National Commission on Human Rights on the arrests, tortures, etc. done post martial law. Likewise, students Ann Dimatulac and Danilo Santos are abducted then killed for participating in marches and demonstrations.

The myriad of monsters in Rosca’s “State of War” is led by Col. Urbano Amor, who wields absolute power without compunction and inflicts suffering without qualms. Anna undergoes painful questioning as Manolo’s wife and for the escape of three activists. Manolo breaks under interrogation and becomes Colonel Amor’s lead chemist in making prisoners “sing” with his chemical inventions. Adrian Banyaga, scion of a wealthy family, goes on a mind trip on Manolo’s pharmaceutical shots, spilling how his grandfather invested in rising political stars and collected on the favors later.

The monsters in “The Collaborators” are corrupt, like a former-actor-turned-president implicated in a jueteng scandal — nicknamed juetengate — by a whistleblower who swears he collected ₱10 million a month in protection money for the president for more than 20 months. Adds the whistleblower: “Jueteng is the poor man’s numbers game. [It’s] an industry worth billions and so cops and mayors are in on it…[and] naturally, the president, too.”

Scariest monsters

Mythology was a way to understand the universe before science. Misshapen monsters stood as symbols of evil to explain the strange and unacceptable. Conversely, beautiful gods were the emblems of goodness and normalcy, a symbolism that extended to humans said to be made in the likeness of deities. Monsters kept people in check — no one wanted the bogeyman coming for them — and, if they transgressed, were chastised until they toed the line.

Tellingly, literature’s good-versus-evil template overlooked a pivotal subtext: the wafer-thin line separating humans and monsters, making physical appearance a faulty basis for judgment. Remember that wolves have dressed up in sheep’s clothing, and so, quoting British actor Jared Harris, “the scariest monsters are humans because you don’t know what they will do to each other.”

Everyone has a potential to become a monster, especially in an environment or situation where other people stoke the depravity to flourish. Child A is exposed to his father’s abuses and violent temperament, and grows up bullying others in “Child A.” Significantly, Hau’s teenaged monsters call to mind the wily adolescent Fonchito who engages his stepmother in an illicit relationship in Mario Vargas Llosa’s “In Praise of the Stepmother.” If one measures the degree of wickedness, who’d be more grotesque: Child A or Fonchito?

Deceit makes monsters of both the cheater and the betrayed, lending credence to the idea that monsters lie just beneath the surface of sanity. Some monsters are more vindictive than others: Lia quietly accepts her daughter having no interest in her, Ellie passively waits for her husband’s new affair, Anna kills Manolo.

Ultimately, authoritarianism creates scourges of humanity, like Colonel Amor who unjustly survives, completes a dissertation, and is “conferred a doctorate in the behavioral sciences” at the end of “State of War.”

Monsters balance out the forces in the universe like yin and yang, but as Hau, Rosca and Tuvera paint in their prose, they are not created in the same likeness. Looks can be deceiving. Hideous creatures can be kindhearted. Those angelic faces can conceal black hearts.