A mother waits for the release of her son from Insein prison. Photo by Myanmar Press Photo Agency.

YANGON/BANGKOK- You pause before picking up a call from an unknown phone number. You’re ready to change plans in a second, if explosions occur in your area or soldiers show up. When going out, you may delete the Facebook app from your phone, lest you get stopped by soldiers wanting to check your posts. If you have COVID-19 symptoms, you look for an antigen test kit before trying to get an RT-PCR test or go to hospital.

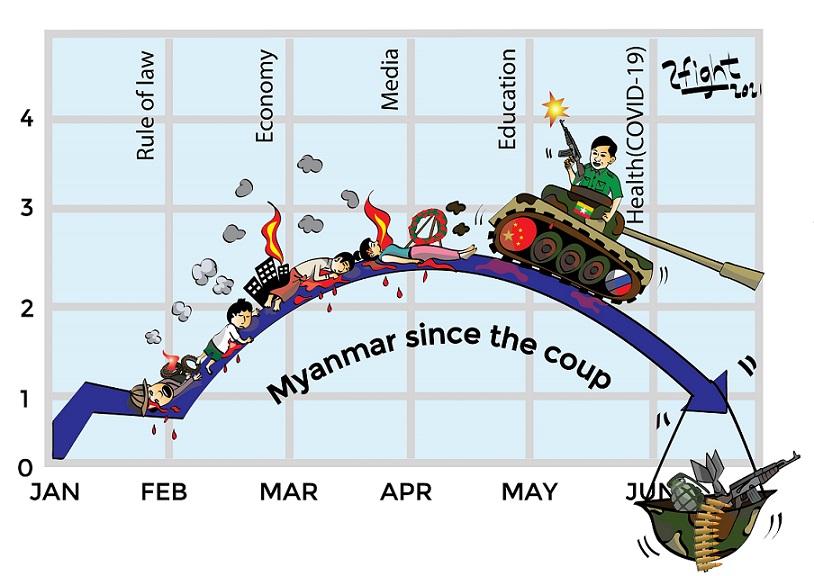

These are among the survival skills that many people in Myanmar are using these days, six months after the February military coup. Hypervigilance has become routine.

Anxiety is never too far away as they make their way through layer upon layer of crises – the political crisis sparked by the military’s ouster of the elected government on Feb 1, the economy’s breakdown amid rising poverty, and a third COVID-19 wave surging in the wake of a collapsed system for delivering public services.

“I always feel insecure wherever I go,” said one resident of Yangon, the commercial capital of this country of over 57 million people. “I dare not bring my phone because I’m scared when I hear that security forces are checking mobile phones, and they also take money. So I never take much money if I go out.”

“I’m also insecure at home because they (soldiers) can check any time and they take whatever they want,” she added.

“There are lots of things to care about when you go outside, not only the COVID third wave but also explosions, people in uniform,” agreed one artist. “Our daily lives are different compared to before, due to COVID and the coup – double trouble – in terms of work security, safety, unemployment.”

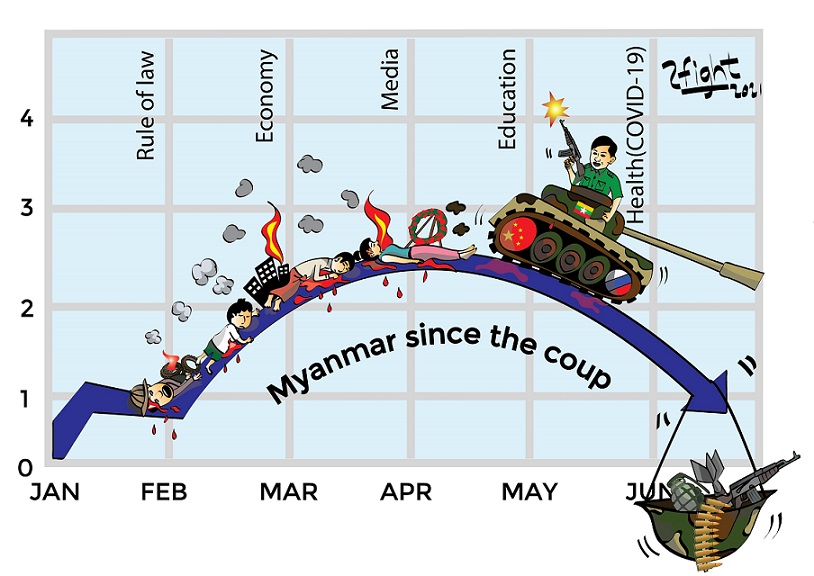

Infographic by Reporting ASEAN

Locals say the price of some goods and medicines, food items have risen by 20 to 40%. Worries abound about the latest harvest and future ones, because farmers (80% are small farmers) depend on credit from the state and fertilizer prices have shot up by 50%. Fuel prices are reported to have nearly doubled since February.

Power outages are worrisome amid a pandemic that sees daily new cases at 4,000-5,000 and over 300 deaths daily. Cases are under-reported as testing is severely limited, and infectivity is very high: 37% of COVID-19 tests were positive, as of Jul 22. Only Mexico’s 38.1% is higher in the One World in Data global tracker.

Cash is a precious commodity, one that can be received after shelling out 6-10% commission fees to brokers and mobile apps. “Wasting our money in these horrible times” is how the owner of a small business puts it. Access to cash has become better in some cases, but long queues are common and limits on cash withdrawals remain.

Even as the pandemic rages – and has affected its ranks – Myanmar’s military has continued to arrest anti-coup protesters, those who have stayed with the civil disobedience movement that started right after the coup.

“Now I’m afraid of going outside and I dare not pick up calls from unknown people,” said one schoolteacher who continues to stay away from her work with the government. “I’m also afraid to answer calls because some officers in our department threaten and force (us) to go back to work. And I’m always afraid of the informers and spies of the military.”

For many, there is too much of the military’s presence in their lives, but too little, or none, of public governance in this catastrophe unfolding in their midst.“It is estimated that up to 90% of national government activity has ceased,” the UN World Food Programme (WFP) said in its June report on the economic fallout and food insecurity in Myanmar since the coup.

As they have learned to do under past periods of military rule, Myanmar’s people are turning to one another, forming networks of their own, to survive.

Communities have been arranging donation drives for those who have lost relatives to the pandemic or are taking care of the sick, and others who are in self-isolation. Volunteers are still driving patients to hospitals, which have run out of beds. Online groups help track supplies of medical oxygen amid the ongoing scarcity. Many share what income they make with the jobless.

Disaster of epic proportions

But still tougher times lie ahead in what Myanmar historian Thant Myint-U calls an “economic and humanitarian disaster of epic proportions”. The economy is expected to contract by 18% in 2021, said the World Bank’s ‘Myanmar Economic Monitor’ in late July. At nearly double the 10% contraction projected in March, it is Southeast Asia’s largest such plunge.

“As the third wave of COVID-19 outbreak struck and strict containment measures were reimposed, an even worse scenario could unfold, with poverty levels in 2022 rising to well over twice as high as they were in 2019 (22.4% in 2018/19), wiping out gains of over a decade of poverty reduction progress,” the World Bank said.

The same report said one million jobs could be lost in 2021 out of a labour force of some 25 million – and this figure excludes workers in the huge informal economy. Already, the International Labour Organization says, 3.1 million full-time equivalent jobs have been lost due to COVID-19 and containment measures.

Migrant workers and those overseas are finding it harder, and often more expensive, to send money into Myanmar, through informal channels. More than 10 million people cite remittances as an income source, says the WFP, and 40% of remittances come from abroad.

Half of households have reported cutting consumption, including food, the World Bank said. Up to 3.4 million more people are at risk of food insecurity, on top of the 2.8 million who were not getting enough food before the coup, the WFP said in its June situation report.

One homemaker said, “We haven’t had income for a long time after this coup. We had to go into home-grown vegetables. It’s so hard to take meals (only) twice a day.”

Many pin hopes on the National Unity Government that was formed on Apr 16. With 16 ministers apart from a prime minister, the government-in-exile reports on meetings with foreign diplomats and parliamentarians, sends officials to speak at webinars. But it is struggling to gain international recognition and faces challenges around having its decisions actually carried out inside the country.

Bodies of Covid 19 victins in queue for burial at the Kyisu cemetery. Photo by Myanmar Press Photo Agency.

As COVID-19 took a turn for the worse in June, its health ministry opened a telemedicine channel on Facebook and formed a national committee with the health organizations of several ethnic groups, but a mechanism for a pandemic response is unclear.

“I would like to appeal to all the people of Myanmar to continue the fight bravely with the spirit of victory in mind,” said Mahn Wann Khaing Thann, NUG prime minister. “When we succeed, our government will repay and work for the establishment of a Federal Democratic Union that all people aspire to.”

The present moment

But it is the here and now that people live in – and like the COVID-19 pandemic, an end to the crisis is not within sight.

“We only have ourselves,” said a Yangon resident. “We have to take care, as much as we can, of food, medicine, oxygen, and other basic needs. The authorities can’t do anything. Unfortunately, it’s like we are waiting for the day we die.”

“I can’t sleep well at night,” confided another local. “Most of my family members are jobless right now. Even though I save money, not spending spend much money, I’m afraid that one day, I won’t be able to make it.”