Public transportation under GCQ

The tranquility that silenced the traffic snarl in Metro Manila’s roads for nearly three months came to an end on June 1, when people returned to the streets after quarantine rules were eased.

However, a different kind of chaos greeted the battle-hardened commuters. They were taken for an unpleasant ride by confusing post-lockdown transport policies.

Indeed, the struggle to balance necessary physical distancing measures and the demand for transport led to big crowds waiting hours for a ride or, worse, being crammed perilously into the back of government trucks.

Dozens were forced to walk to their places of work, starting off way before dawn to reach their destinations. Many opted to use bicycles as an option to long waits for a train.

Tensions between frustrated commuters and transport officials came to a head after the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority (MMDA) said it would fine and cite one cyclist group for obstruction for putting up a makeshift bike lane with bright orange plastic bottles on Commonwealth Avenue in Quezon City.

This drew criticism from many groups that called out transport authorities for being insensitive to the needs of the public.

Commuter advocates and road safety experts said in a June 8 online forum that the government must implement new mobility policies fit for the “new normal,” instead of trying to enforce old ones.

“This whole COVID-19 situation has been very revelatory for us,” said lawyer Sophia San Luis, executive director of the legal advocacy group ImagineLaw.

“For the longest time, a lot of our institutions have been held up by scotch tape and band-aids,” she added. “Temporary troubleshooting is what the government has always introduced. And we see now with COVID-19 that this is not sufficient.”

San Luis also said even before the COVID-19 pandemic struck, the country’s roads had already been “inhospitable” for commuters.

New mindset on mobility

“While our public transportation system can be transformed by policy, a lot of the things that can be fixed can be fixed by political will,” she said. “What we are seeing from government is that the changes they are making are not really equivalent to the changes that are needed.”

A biker waits for traffic to move

Public transport advocate and columnist Robert Siy, meanwhile, said that the government and society need to change their mindsets on mobility.

“Many of our agencies are still stuck in an old-century paradigm that we need to maximize the speed and throughput of cars,” he said. “There’s a saying that widening roads to solve traffic is like curing obesity by buying bigger pants.”

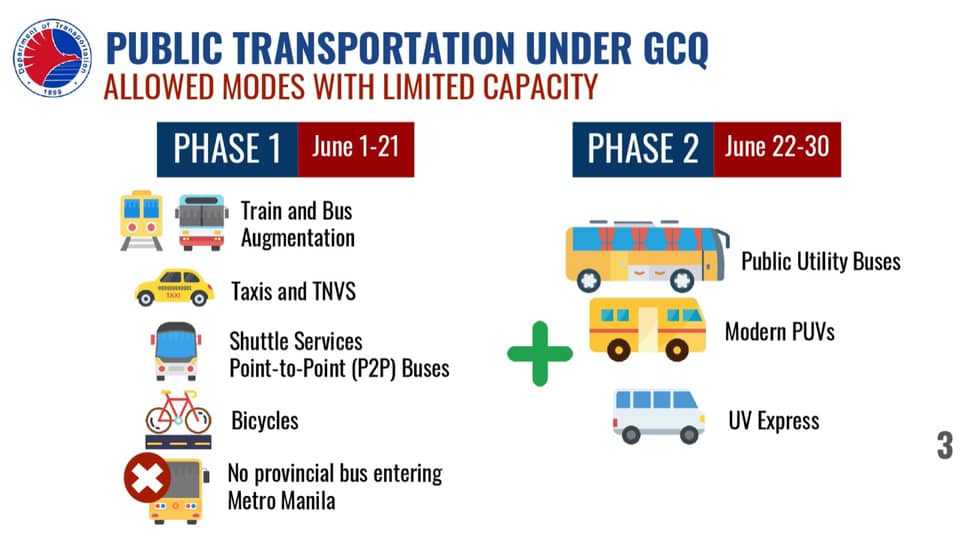

Prior to the implementation of General Community Quarantine (GCQ), several government agencies had released guidelines to aid commuters who need to travel under the ‘new normal’,

highlighting the need to keep the required physical distance.

To make sure there will be no crowding in public transport, the Department of Transportation (DOTr) announced on May 2020 its Omnibus Public Transport Protocols the following:

- Reduced maximum passenger capacity on trains (12 percent for LRT-1, 10 percent for LRT-2, 13 percent for MRT-3, 20 percent for PNR)

- Reduced maximum passenger capacity for private vehicles and PUVs

- Ban on backriders for motorcycles

- Promotion of bicycles and personal mobility devices

The agency added that from June 1 to 21, only buses, trains, taxis, Transport Network Vehicle Services and point-to-point buses would be allowed to operate. Starting June 22, modern PUVs and UV Express vehicles can also operate.

Meanwhile, cities like San Juan and Mandaluyong have established bike lanes on their roads. This is in addition to the extensive bike lane networks already in place in Marikina and Pasig.

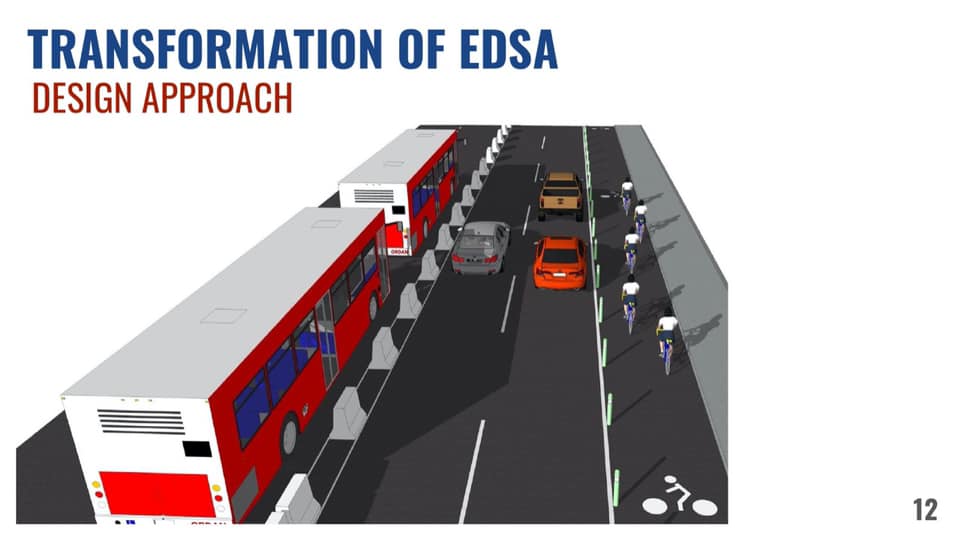

This is how EDSA is envisioned

The DOTr also plans to transform EDSA to accommodate other forms of mass transport. The 24-kilometer thoroughfare is a major artery that runs through six Metro Manila cities and has long been plagued by severe congestion, leading to hour-long commutes and jam-packed buses and trains.

The plan states that buses will use the innermost lane of the thoroughfare and will include stations and pedestrian overpasses connecting the sidewalk and the center island. The lane/s after this would be for motor vehicles. Finally, the outermost lane would be designated as a dedicated bike lane.

Clashing viewpoints

However, transport authorities are still at odds over how to deal with bicyclists on EDSA.

MMDA Spokesperson Celine Pialago said the agency is proposing fenced bike lanes on the sidewalk to better protect cyclists.

“EDSA averages 86 car accidents daily. It’s very dangerous. We understand the bikers’ call for one lane, but for the length of EDSA and major thoroughfares, we are really pushing for elevated lanes.”

She said MMDA is just waiting for the budget to start the project, adding that construction can be completed in a month.

MMDA Spokesperson Celine Pialago holds up copy of road plan

Urban planner Keisha Mayuga, a cyclist who is part of the Move As One commuters coalition, contended that a dedicated lane would actually be safer than making cyclists ride on the sidewalk.

“One study estimated that the crash rate for cyclists on the footpath was 5.6 times than that of cyclists on the road,” she told VERA Files. “Creating protected bike lanes at-grade would slow down cars and protect the cyclists currently plying these roads.”

Mayuga added that making bike lanes on the sidewalk would cost taxpayers P3.8 million per kilometer due to numerous adjustments like drainage, lighting and fencing. However, she said a bike lane on the road would cost just P1 million per kilometer for paint, signs and bollards.

“DOTr suggests to take one car lane that is around 2.3 meters wide, which is perfect,” Mayuga said. “MMDA specs are at one meter, counting some obstructions and it is shared with pedestrians, which is even worse.”

DOTr Senior Consultant Alberto Suansing, who is also the head of the Philippine Global Road Safety Partnership, said putting cyclists on the sidewalk would not be a good idea.

“‘Yung bangketa natin dito along EDSA, hindi pantay-pantay,” he said. “May mga driveway, may pataas, may pababa, so it would be difficult for a biker na gamitin. (The sidewalks along EDSA are not even. There are driveways and inclines that go up and down, so it would be difficult for a biker to use).”

Suansing said the DOTr and MMDA are coordinating with each other but admits “there is some disagreement”. He added: “Where the bicycles lanes will be located, that is the question that is still being deliberated with MMDA.”

Providing options, saving lives

But for some, resolving these transport issues promptly is a matter of life and death.

Cyclist and doctor Antonio Dans said besides helping people get around, one of the main advantages of biking is that it could prevent non-communicable diseases like diabetes, hypertension and obesity.

Bikers share road with motorists

“But now, during the pandemic, you can see it’s also a means to prevent communicable disease because it’s a way to commute in a physically distant manner,” he said. “This is especially important to healthcare workers because when we go on duty, the workers quarantine themselves to prevent spreading infection to other people.”

Dans added that at the Philippine General Hospital, one in every four employees is a cyclist, with around 95 percent of them biking for the first time.

Former CNN and Time Beijing Bureau Chief Jaime FlorCruz noted how China became renowned for its bicycle usage, particularly in the 1970s.

“Millions and millions of commuters rode a bicycle and, in a way, it was a symbol of socialist China,” he said. “Everyone is equal. Even mayors rode bicycles. And it led to many good things – healthy, no traffic, no pollution.”

By the 1980s, however, FlorCruz said China began to embrace more automobiles as it aggressively pursued economic expansion and urbanization. But the global superpower had a “rethink” over by the start of the new millennium, leading to a resurgence in popularity for bicycles.

“In one dating program in China, one of the contestants said ‘I’d rather cry inside a BMW than laugh on a bicycle,’” he said. “That kind of crystallized the debate about how bicycles should be promoted instead of being looked down as a poor man’s commute.”

Siy also said prioritizing other commuters is only logical since only around one in 10 Metro Manila households have cars.

“People will be injured and will die simply because we are trying to protect the interests of 12 percent of our population in Metro Manila,” he said. “Here in the pandemic, the imperative for all of us is to protect those who are most vulnerable and those who are less privileged.”