By ELLEN TORDESILLAS

Ombudsman Conchita Carpio-Morales has asked the Anti-Money Laundering Council for a copy of the records of impeached Chief Justice Renato Corona’s bank deposits, including dollar accounts that are the subject of a temporary restraining order issued by the Supreme Court.

A highly placed source in the Office of the Ombudsman confirmed that Carpio-Morales sent the request after her office received a complaint seeking an investigation on Corona’s supposed ill-gotten wealth and possible money laundering. But AMLC Executive Director Vicente Aquino said he was not aware of such a letter in his office. “We have not received such request,” he said.

Aquino also said he refuses to talk about Corona’s assets in the media, calling it a “sensitive” issue.

The Anti-Money Laundering Council is composed of the governor of the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, the Insurance Commissioner and the Securities and Exchange Commission chairperson.

Carpio-Morales’ request was precipitated by the complaint filed on Feb. 17 by a group of individuals that included former Akbayan Rep. Risa Hontiveros-Baraquel asking the Ombudsman to probe Corona’s possible illegal accumulation of wealth, a violation of Republic Act 3019, the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act.

The group also asked that Corona be investigated for possible violation of RA 9160, the Anti-Money Laundering Act. The other complainants are Harvey Keh of Kaya Natin, Ruperto Aleroza of the Pambansang Katipunan ng mga Samahan sa Kanayunan (PKSK), Albert Concepcion of PUSO and Gibby Gorres of the Student Council Alliance of the Philippines (SCAP).

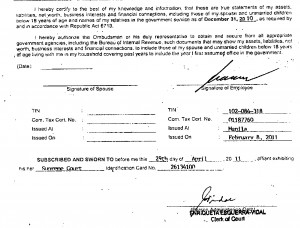

A paragraph at the bottom of the Statement of Assets, Liabilities and Networth (SALN) form serves as a waiver that, when signed by government officials and employees including Corona, empowers the Ombudsman to access from government agencies relevant records needed to examine their networth declarations.

The waiver reads, “I hereby authorize the Ombudsman or his duly representative to obtain and secure from all appropriate government agencies, including the Bureau of Internal Revenue, such documents that may show my assets, liabilities, networth, business interests and financial connections, to include those of my spouse and unmarried children below 18 years of age living with me in my household covering past years, to include the year I first assumed office in the government.”

On March 6, the Senate, sitting as an impeachment court, decided to admit Corona’s bank records, including his dollar deposits, as evidence despite suspicions that the prosecution had gotten them through illegal means.

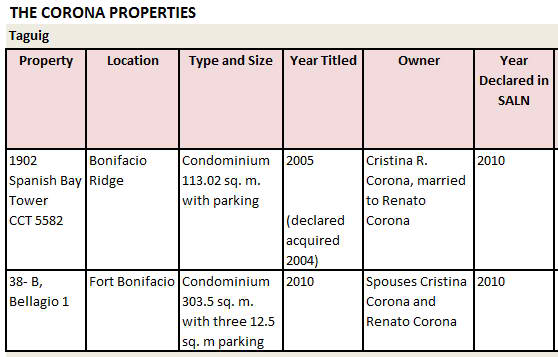

The prosecution has presented to the Senate 10 accounts the Chief Justice had opened with the Philippine Savings Bank’s Katipunan branch, five of them dollar accounts, to substantiate Article 2 of the impeachment complaint. Article 2 charges that Corona failed to make public his SALN, omitted to include a number of properties from his declarations, and might have accumulated ill-gotten wealth, including “keeping bank accounts with huge deposits.”

One of the dollar accounts reportedly showed an initial deposit of $700,000. Sources, however, said the sum of the dollar deposits was “mindboggling.”

Corona has said in media interviews that he was willing to open his dollar accounts “in due time.” His lead counsel Serafin Cuevas told the Senate on Wednesday, “I have not yet concretely and positively arrived at the ultimate conclusion that we have to or we do not have to. That will depend on the progress of the proceedings in the nature of our evidence or the stages at which our evidence may be.”

The Supreme Court, voting 8-5, granted on Feb. 9 PSBank’s petition to issue a TRO on the Senate subpoena for the bank to submit records of Corona’s dollar deposits, citing the law on foreign currency deposits (RA 6426) that classifies foreign currency deposits as “absolutely confidential.”

“(E)xcept upon the written permission of the depositor, in no instance shall foreign currency deposits be examined, inquired or looked into by any person, government official, bureau or office whether judicial or administrative or legislative, or any other entity whether public or private,” states RA 6426.

In his dissenting opinion, however, Associate Justice Antonio Carpio said the guarantee of secrecy under the foreign currency law applies to nonresidents to encourage the inflow of foreign currency deposits into the country.

He said the TRO makes a mockery of all existing laws designed to ensure transparency and good governance in public service as it will encourage government officials and employees to hide their true wealth under a foreign currency bank account.

The Supreme Court en banc is expected to decide on PSBank’s petition on Tuesday before it goes on a break.

Signed in 2001, the Anti-Money Laundering Act or RA 9160 defines money laundering as a crime whereby the proceeds of an unlawful activity are transacted or attempted to be transacted to make them appear to have originated from legitimate sources.

The law requires banks and similar institutions to report to the AMLC within five working days any transaction that exceeds P500,000 within one banking day, called a “covered transaction,” and “suspicious transactions.”

A transaction, regardless of the amount, can be considered “suspicions” for the following reasons:

• There is no underlying legal or trade obligation, purpose or economic justification.

• The client is not properly identified.

• The amount involved is not commensurate with the business or financial capacity of the client.

• It may be perceived that the client’s transaction is structured in order to avoid being the subject of reporting requirements under the AMLA.

• Any circumstance relating to the transaction which is observed to deviate from the profile of the client and/or the client’s past transactions with the covered institution.

• The transaction is in any way related to an unlawful activity or any money laundering activity or offense under this act that is about to be, is being or has been committed.

When he took the witness stand last month, PSBank President Pascual Garcia III said a Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas examiner told the bank to put the notation “PEP” on Corona’s records.

Under AMLC rules, elected and appointed public officials are considered “politically exposed persons” or PEP. – with Yvonne T. Chua