VERA Files is 10 years old.

To mark our 10th anniversary, we are reposting 10 stories that mirror the group’s interest and commitments.

What would you do if a group of policemen showed up at your doorstep and asked you to pee into a plastic cup for an on-the-spot drug test that could reveal whether or not you had taken shabu or marijuana in the last seven days?

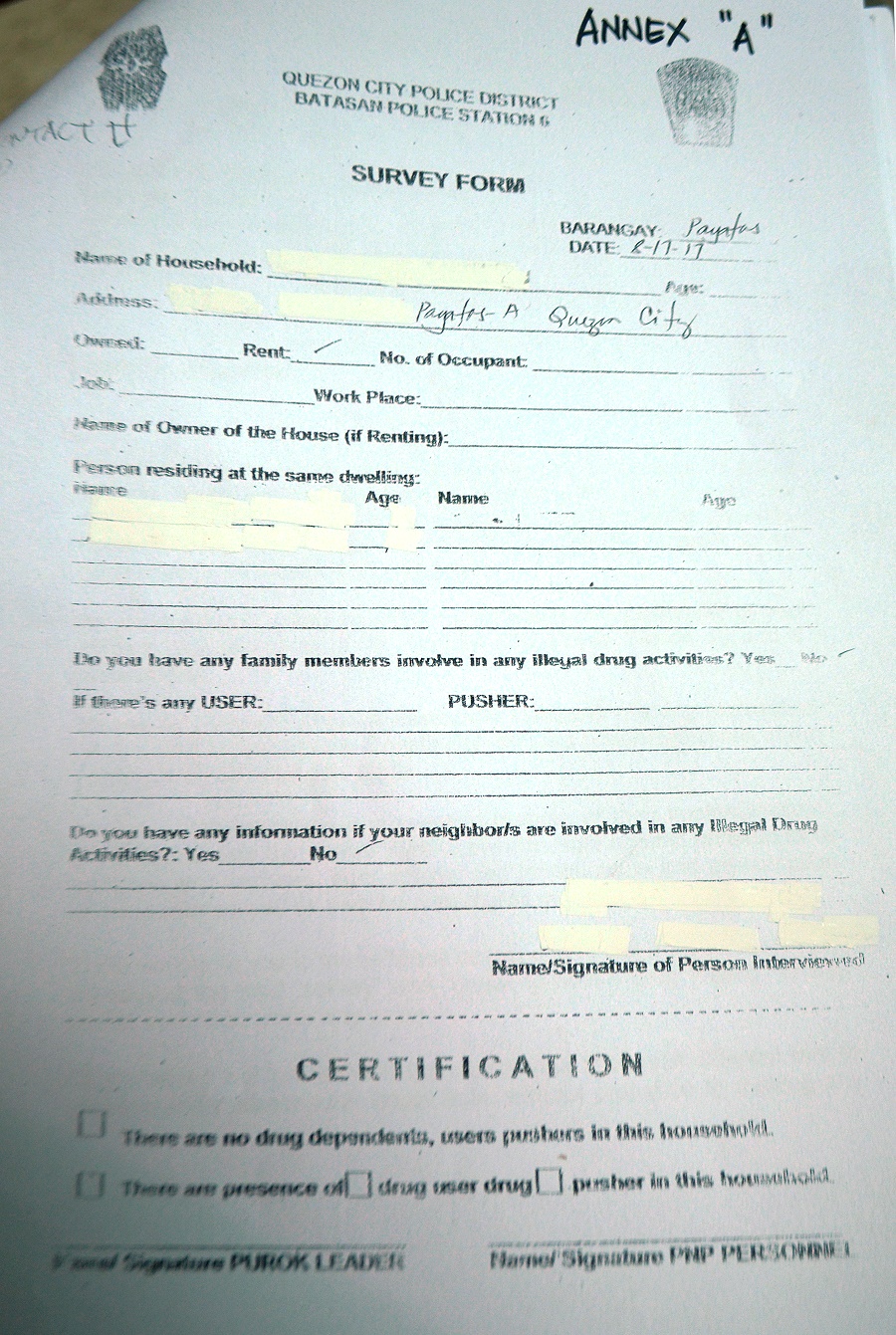

That is the question residents of Lupang Pangako in Barangay Payatas have been grappling with since June when groups of policemen started going house-to-house, armed with do-it-yourself drug testing kits that show, within seconds, that a person is either positive or negative for the use of those banned substances.

Answering the question is not easy, even if you were clean and had nothing at all to fear. One 19-year-old boy who was asked to take the drug test in place of his father who was the person the police were actually looking for, had no choice but agree to do it. Yet he could not get himself to pee, possibly out of fear, despite two tries and the police telling him to drink water.

In another home, the police went looking for a woman, but also did not find her there. Instead, it was her grandmother who opened the makeshift gate. The policemen asked her to take the test. “Bakit ako, hindi naman ako gumagamit? (Why me, I’m not a user?),” the grandmother asked. The policemen explained that the test covered those on their list as well as relatives who might be home when the police came visiting. The grandmother also insisted that the woman the police were looking for had already been cleared.

The grandmother eventually relented, and as she expected, tested negative for drugs. Trying to make light of the situation, she asked the policemen, “Lumabas ba diyan na may sakit ako sa bato? (Did it say that I have kidney stones?)” she joked.

This is what government’s latest version of its war against drug addicts looks like, at least here in Payatas and in the neighboring barangay of Batasan Hills, where the drug testing has reportedly been completed. Officials call it a “massive drug clearing operation,” with police conducting surveys of occupants of all houses, mapping the village, and then showing up unannounced and making people take drugs tests or be called “uncooperative” if by chance they decide to say no.

It is the approach local leaders prefer, because it does not involve killing and the barangay is taking active part in it, with support from the police.

“Noon, binabaril agad (Before, suspected drug users were shot right away),” said Barangay Captain Julieta Peña of Payatas, the fifth most populous of the country’s 42,000 barangays, according to the 2015 national census.

In other parts of the country, though, the summary executions gained new momentum as Pres. Rodrigo Duterte entered his second year in office. Police operations in Bulacan have resulted in 32 dead in just one night alone, while 21 were killed in Manila, and seven in Cavite, also in the span of just a night.

In Caloocan City, among the victims was 17-year-old high school student Kian delos Santos who the police said was a drug runner. His family has denied the accusation, and CCTV footage showed the police taking him over his objections.

This is why the drug testing approach seems to offer an alternative. But Fr. Michael Sandaga, parish priest of Lupang Pangako, said the operation is tantamount to coercion because people are subjected to drug testing against their will.

Actually, Republic Act 9165 or the Dangerous Drugs Acts also specifies that drug tests must be done by “government forensic laboratories or by any of the drug testing laboratories accredited and monitored by the DOH to safeguard the quality of test results.”

Besides, the law lists only those who should be subjected to drug tests: applicants for drivers’ licenses, applicants for firearms licenses, high school and college students, officers and employees of public and private offices, members of the police, military and other law enforcement agencies, those charged with crimes whose penalties are more than six years, and all candidates for public office, whether appointed or elected.

The law says nothing about policemen conducting community drug tests.

“After the testing, what would happen?” Sandaga asked.

“When found positive, a person’s name is placed on a watch list,” said Barangay Kagawad Alejandro Adan, chairman of the barangay’s peace and order committee.

Adan however said people here opt to either confess their drug use and surrender rather than undergo testing. They are also advised to come clean, so that they could be given a second chance. He also talks about “interventions” like livelihood programs for those who surrender or those found positive.

In the barangay’s master list are 4,595 names, as of June 18, 2017, of people suspected of using drugs. Some have been arrested, some surrendered and some have been killed.

Oplan Tokhang, though, is a thing of the past, Peña said, and it has been abused and taken advantage of. Although the killings continue, barangay officials couldn’t really say who is behind them.

But it is unlikely that a DIY drug testing campaign will solve the drug problem in Payatas, listed in the 2015 census as having a population of 130,333 that in reality doubles as the number of transients swells, specially at night, barangay officials said.

Part of the Payatas dumpsite that collapsed and buried more than 200 people is now a hill of green looming over Lupang Pangako. Photo by Luz Rimban

Payatas shares borders with Barangays Bagong Silangan, Commonwealth and Batasan Hills, the last two being second and third most populous barangays of the country. Together with Payatas, they make up a hotbed of drug use and trade. Local government and church officials said users and pushers simply slip from one barangay to another, or toward neighboring San Mateo or Montalban, to escape anti-drug campaigns, and return when the heat has subsided.

The drug problem is also especially complex in these villages where drug use is not the “young and recreational” type it is elsewhere, as some social scientists from the Ateneo de Manila found in a study they conducted late last year. Drug use here has mainly an economic dimension to it.

Among those who use drugs in places like Payatas are tricycle drivers, vendors and even washerwomen. Drugs give their bodies the boost they need when they get tired. “Tamang sipag (enough energy)” is a term the academics heard people say is the offshoot of drug use, in a study done in a community nearby.

Payatas’ workforce no longer consists of just scavengers, and its cemented streets are a far cry from the muddy fringes of a dumpsite it used to be. Houses are made of concrete and people enjoy electricity and running water.

Sandaga said Payatas breadwinners include construction or factory workers, or young professionals, or those working in malls and call centers. Many people who live here find cheaper rent compared to other places in Quezon City.

But financial pressures force them to take on more than one job, Sandaga said. “Call center agent ka, pag uwi mo mag-Uber ka pa (You’re a call center agent, and then you get home you become an Uber driver),” he said. These kinds of workers push themselves to the limit, and are sometimes forced to take drugs or alcohol.

The names on the policemen’s list included those of a construction worker and an office worker. These people were not home but relatives were, and it was the relatives who were asked to take the drug tests instead.

After asking people to pee into plastic cups, a policeman then dipped the testing stick into the cup and read the results within seconds. Red and pink lines mean a person is negative for drugs. A single line means he or she has used either shabu or marijuana in the last seven days.

Unlike blood tests that can tell whether a person has used the substance for the past six months, DIY drug kits can only tell who have been using drugs for the past week, the barangay officials said. The drug testing kits cost P100 each, and the barangay is obliged to pay for them.

Results of a drug test show pink and red lines, indicating the person tested was negative for shabu or marijuana. Photo by Luz Rimban

It is also the barangay that shoulders the cost of feeding 200 policemen and purok leaders combing the community on a daily basis. “Araw-araw nagpapaluto kami. Wala kaming budget sa barangay. Di kami naka IRA (We have food cooked every day. We have no budget in the barangay. We are not on Internal Revenue Allotment),” Peña said. The cost could easily go into the millions of pesos every month.

This is why what is supposed to be a massive drug clearing operation is in reality quite selective, one ward leader said. The policemen usually single out the homes of people whose names appear on a list supplied by the ward leaders, who themselves could be accused of pointing the finger at the users, Peña said. A ward leader can have as many as 70 households under his or her jurisdiction.

Sandaga said he has expressed his concern to Peña. He said the barangay needs to inform the public about what would happen to them if they are not cleared. He also said the barangay should make the distinction between those who are frequent users and those who are not. Sandaga is also concerned that neither the parish nor the barangay has provisions for rehabilitation services for those who surrender.

Peña herself admits it’s not an easy task. “Sa tingin ko drugs kasi, mahirap linisin (I think it would be hard for us to get rid of drugs),” she said.

“Akala ko noong araw, kabataan lang ang gumagamit (I used to think only the young use drugs),” Adan said. “Ngayon kahit edad 60 plus (Now even 60-year-olds do).”

“Ang drug problem, mahirap ito (The drug problem is a difficult one),” said Sandaga.

Poverty lies at its root. Selling drugs becomes a source of easy money and using drugs becomes either a means of pushing oneself to work or coping with the depressing situation.

The scavengers are one group prone to drugs. “In order for people to sustain their activities in the dumpsite, some of them use drugs,” said Sandaga. “24 hours ka diyan, sa baho niyan, di mo makakayanan (You’re there for 24 hours. You couldn’t take the stench).”

Peña said she had a census done and found that there are more than 2,800 scavengers in the dumpsite, some of who live in Bagong Silangan and come only for the arrival of trucks that dump garbage. When the rains come, the stench from the dumpsite could be overpowering.

Peña, Adan and Sandaga all cite the raid on the community last year when the police arrested some 100 people. “It was a pot session among scavengers, and they shared shabu, which could be bought for just P100,” Peña said. One hundred eighty people were involved, but only 80 tested positive.

In a report by the Philippine National Police National Capital Region Police Office in its website, the incident is listed has having taken place in Group 3 of Payatas Area 3. A scavenger and a policeman on AWOL were killed and 95 were arrested. The NCRPO report said, “The policeman was a known distributor of shabu in Brgys. Payatas and Bagong Silangan.”

In the meantime, people still get killed here in Payatas. Barangay officials would not discount the possibility gunfights happen between people involved in the drug trade. “May bumabaril na di namin alam. Kapwa pusher, kumpetisyon. Kapag may alam ka sa galaw nila, papatayin ka na nila. (There are killings we don’t know who is responsible for. Possible fellow pushers because of competition. If you find out about their moves, you get killed.) ,” Pena said.

“Sila sila na nagpapatayan. Pag di ka nagbayad, patay. (They kill each other. If you don’t pay up, you’re dead),” she added.

The streets of Payatas have always been unsafe. Holdups, rape, snatchings have happened in broad daylight. Riots would break out with warring groups using sumpak or improvised guns. But barangay officials say the crime rate has gone down, proof of this being that taxis now no longer fear entering the community. The paved roads also make walking a more pleasant experience.

A woman in her 60s from Group 6 in Payatas B does not agree. She lives by the roadside, she said, and in the days before the war on drugs, she and her neighbors would find themselves still up at 11 p.m. seated at the gutters and chit-chatting.

“Pero ngayon, alas otso, alas nuwebe, inside the house na, (Now, at 8 or 9 p.m., we are inside the house),” she said.

“May nagsasabing mga pulis na mas magandang sumurender kayo, may tsansa pa kayo (Some policemen say it’s better to surrender. You still have a chance),” she said. She remembers the policemen’s advise: “Pag di kayo sumurender, ang katakutan ninyo kapag hindi naka uniporme ang kumatok sa bahay nyo (If you don’t surrender, fear the people who are not in uniform knocking at your door).”

First published on Aug. 21, 2017