Since she was seven years old, Manang Bebe, now 69, has heard of plans to build a bridge that will connect Davao City to Samal Island.

Now, as she looks across the Samal docking port, workers are installing poles and setting up the craneway. She never thought the bridge would be built in her lifetime, but construction started six months ago.

“Malipay ko na makasulod na ang daghang negosyo tungod niining tulay (I’m happy that this will bring in more investors),” she said.

Samal Bridge was one of the 75 priority projects under the Build-Build-Build program of former president Rodrigo Duterte, who was also Davao City mayor for more than two decades.

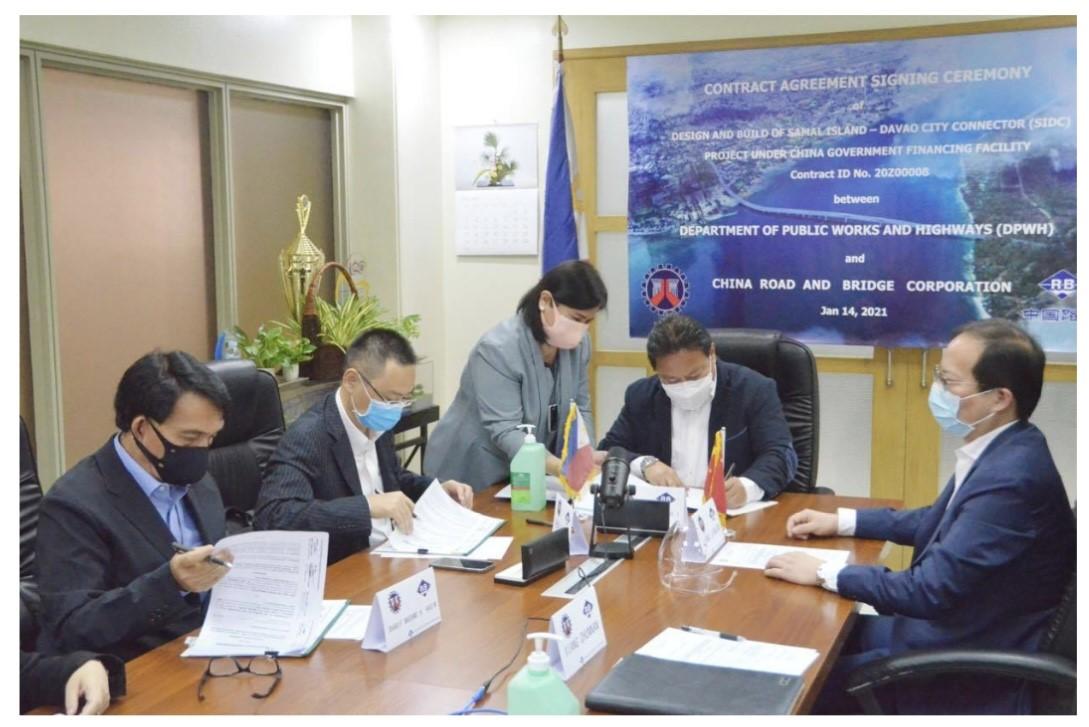

On Jan. 14, 2021, the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) inked an agreement with China Road and Bridge Construction (CRBC) to build the Samal Island – Davao City Connector (SIDC) Bridge at a cost of ₱23 billion, of which P19.32 billion will be a loan from the Export-Import Bank of China.

Seventeen days before Duterte stepped down when his six-year term ended in June 2022, then-Finance secretary Carlos Dominguez III and China’s ambassador to the Philippines, Huan Xilian, signed the framework agreement for the concessional loan.

The project was then included in President Ferdinand Marcos Jr’s 12 mega-bridges under his administration’s infrastructure development program Build Better More.

When Marcos led the lowering of a time capsule to signal the start of the bridge’s construction in October 2022, he described China as “a dependable partner” in its funding.

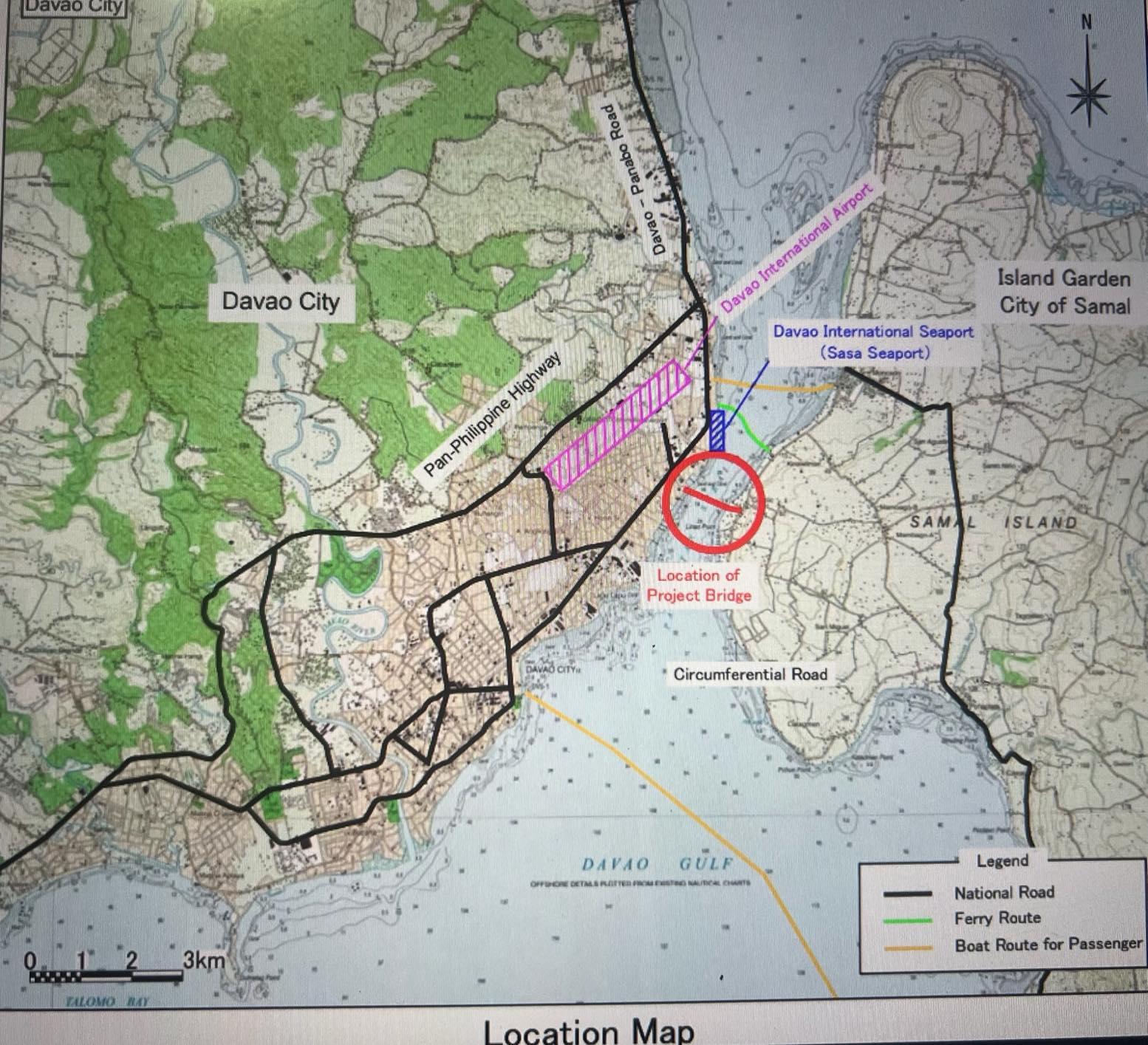

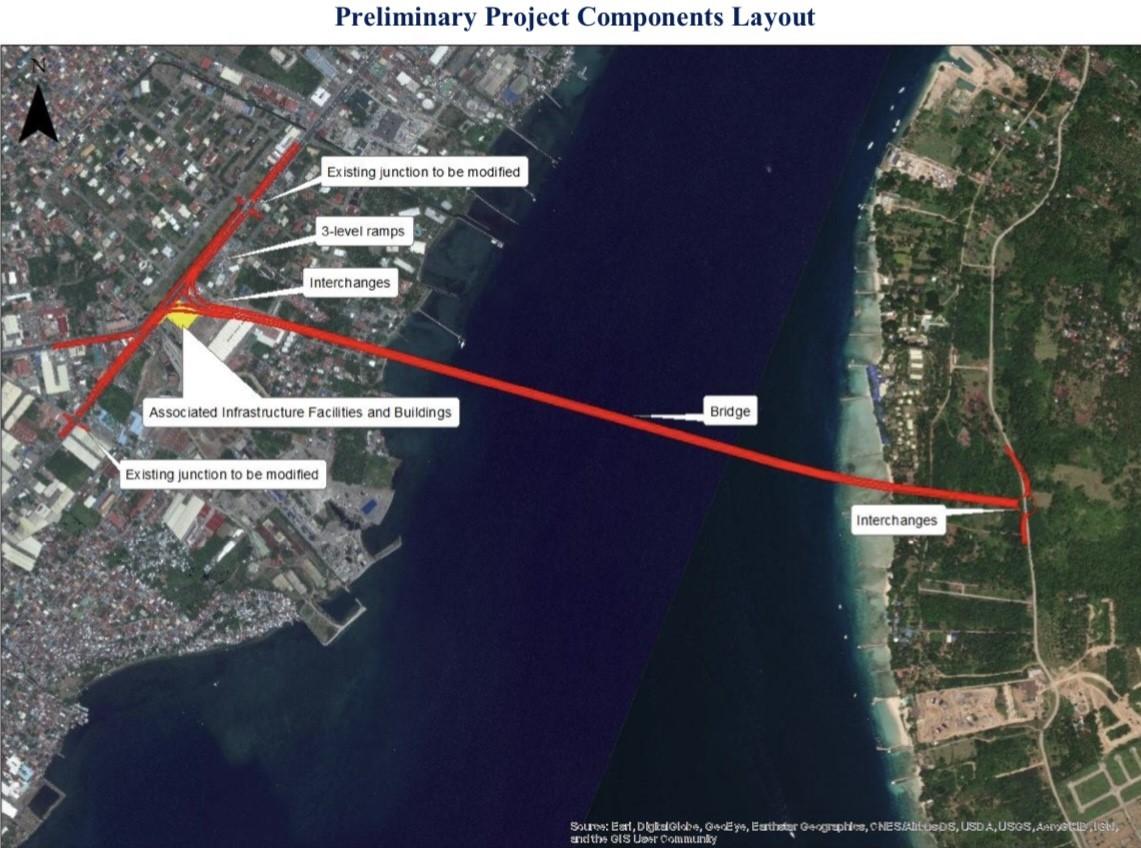

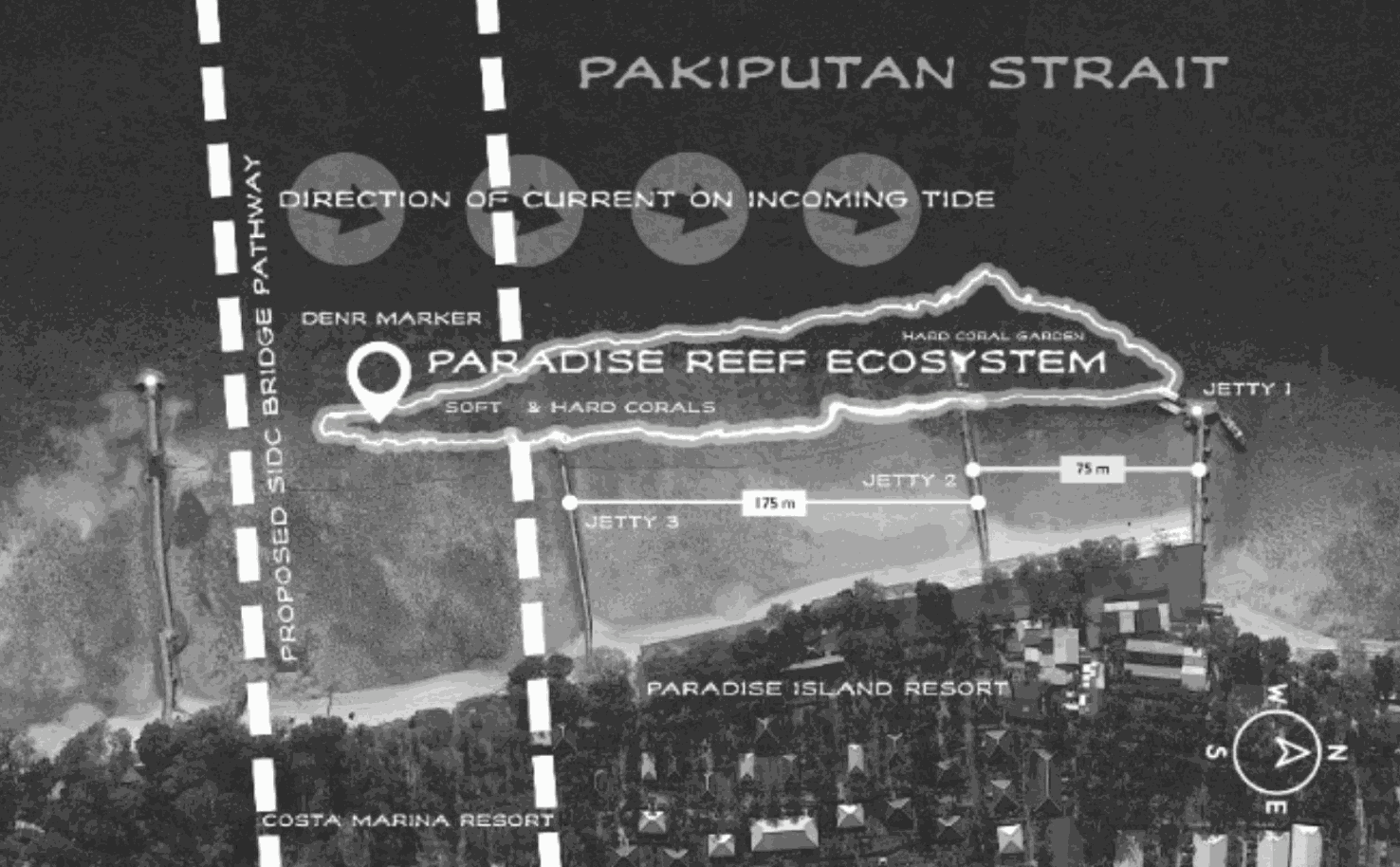

The SIDC bridge will run a stretch of 3.98 kilometers, crossing Pakiputan Strait. It has been projected to cut down travel time to three minutes, from a 20-minute boat or ferry barge ride, which is exacerbated by a one to two-hour wait for motorists before boarding a ferry barge.

Marcos said: “In 2027, this bridge will surely ease the convenience of travel and transport, bringing forth gainful opportunities for many of our people by providing a link between relatively far-flung areas and economic centers, thereby ensuring smoother mobility of people and of goods.”

The bridge, once completed at the new target date of September 2028, will surely bring jobs, transportation and development to the city, said Roanna Padilla, a 65-year-old Samal resident who commutes daily between Samal and Davao City to report for work in a government office.

The DPWH projects the bridge would bring 25,000 vehicles a day into Samal (formally known as Island Garden City of Samal o IGaCoS), which could transform the bucolic island city with 116,000 residents into a booming tourism spot.

These common sentiments of Samal residents have worried environmental groups and a family that has protected the island’s reefs for years.

Lawyer Romeo Cabarde Jr. from the Ateneo de Davao Public Interest and Legal Advocacy (APILA) said the views of many residents show their lack of awareness on the impact of the bridge on the corals.

He said the coral ecosystem is invisible as it is underwater, so it seems okay for the people if they are damaged. But it is like the rainforest of the ocean, helping fight climate change and absorbing a certain percentage of heat from the water surface, Cabarde added.

The Lucas-Rodriguez family, one of the pioneer investors in Samal, points out that the bridge construction will destroy corals and affect the pristine waters that make Samal beaches a favorite destination.

The family owns the popular Paradise Island Park and Beach Resort and the adjacent Costa Marina in Barangay Caliclic, which is the landing site of the SIDC bridge.

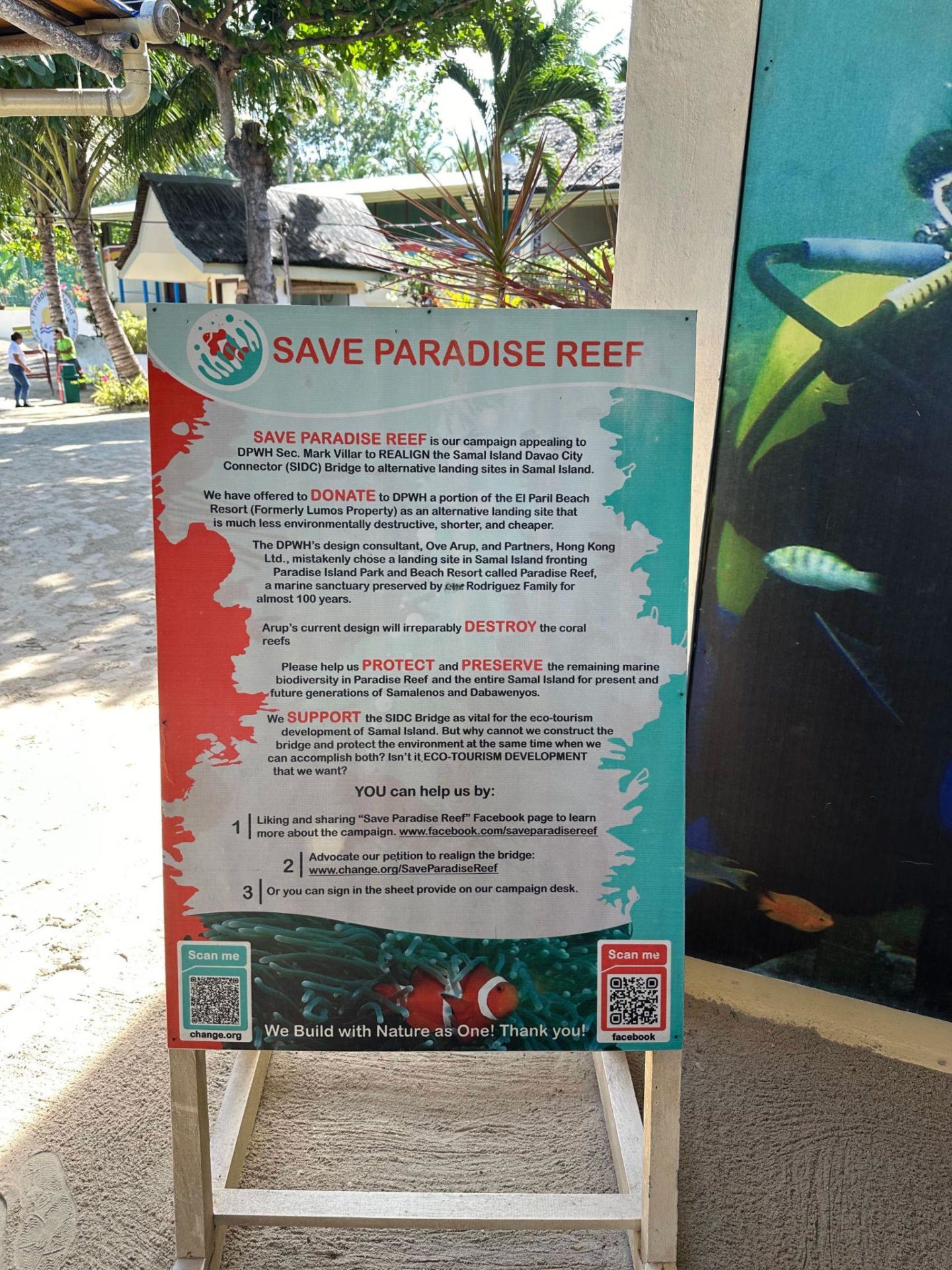

Julian Rodriguez, manager of Paradise Island, said they are actually supportive of the bridge construction, which has been pushed for many decades to help boost tourism in Samal.

But they oppose the location of the bridge, claiming it will destroy the reef.

“We’ve been protecting the reef for 50 years since Paradise has been here. We have been very protective of that reef until now. So, we were surprised that [it is] lacking studies and still they pushed through with the project,” Rodriguez lamented in an interview in April.

He noted that Paradise Reef is an “underwater garden” of at least 7,500 square meters of corals. Based on a study the family had commissioned, the reef hosts 79 species of hard corals, 26 species of soft corals and over 100 species of fishes.

Shorter, cheaper, less destructive landing site option set aside

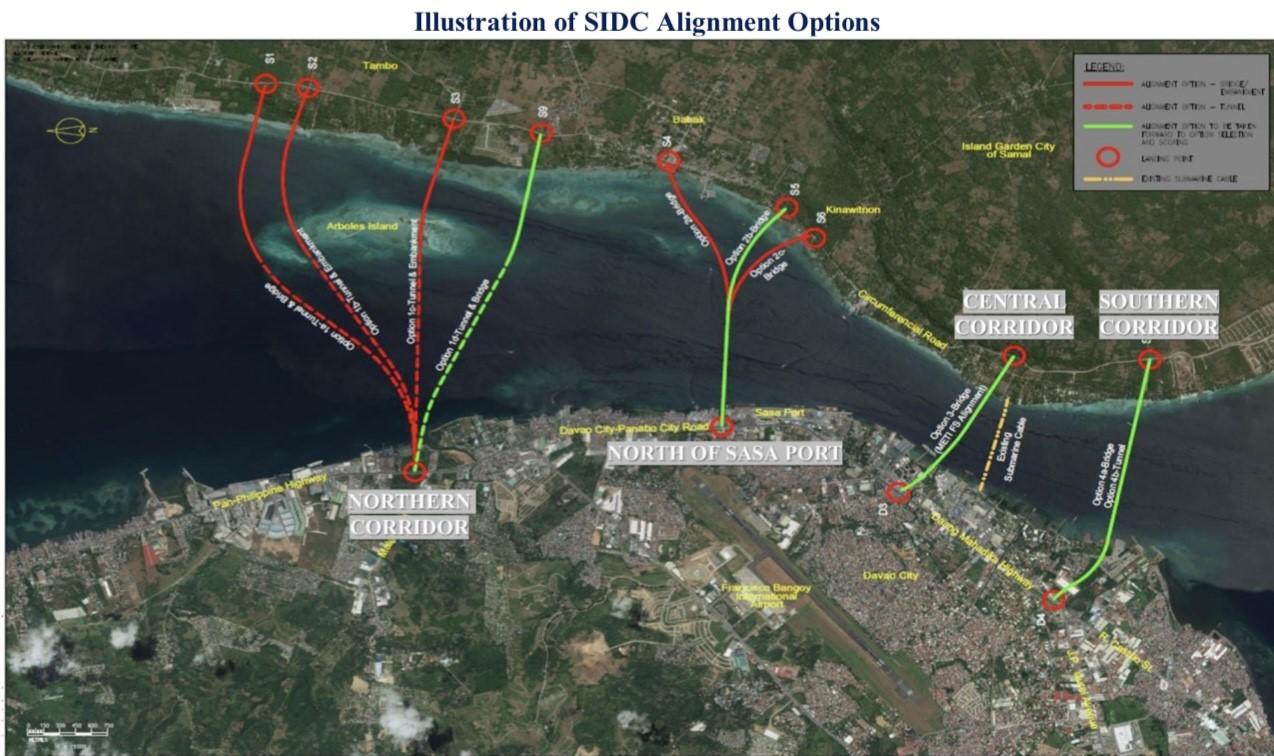

The Rodriguezes pointed to a 2016 study by three Japanese firms —Katahira & Engineers International, Nippon Engineering Consultants Co., Ltd. and Nippon Steel & Sumitomo Metal Corporation— for Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry which suggested an old shipyard known as Bridgeport as an ideal landing site that would have less impact on the environment. It would also be shorter and cheaper, considering its proximity to Davao City.

The Rodriguez family also commissioned in 2019 a team of marine biologists that conducted a biophysical assessment of the three proposed landing sites and found that Bridgeport “has the least biologically productive area,” thus, the best option.

To minimize destruction to the reef, the family has offered to donate a portion of El Paril Beach Resort as an alternative landing site, showing that they are not after money, as they have been portrayed by a series of posts on social media.

Last year, the Rodriguezes petitioned the Court of Appeals (CA) for a Writ of Mandamus, a legal remedy that compels government agencies to enforce environmental laws. It was rejected and they elevated the appeal to the Supreme Court in March 2023.

The CA dismissed the petition over jurisdiction issue because it bypassed the municipal and regional trial courts.

The petition calls for a review of the project’s procedures and documents, including the DENR’s issuance of an Environmental Compliance Certificate (ECC).

Carmela Marie “myLai” Santos, director of the Ateneo de Davao University-Ecoteneo and co-secretariat at the local civil society group Sustainable Davao Movement (SDM), said in an interview in May that they have been supporting the bridge’s realignment, believing that there are cheaper, shorter and less destructive alternatives.

“Clearly, there are other available options that will spare the marine protected area of [Barangay] Hizon and the Paradise Reef. Aralin nilang mabuti ‘yung ibang options nila (They should thoroughly study other options),” Santos said.

The SIDC’s landing point in Davao is in Barangay Hizon, a marine-protected area included in the city’s Comprehensive Land Use Plan for 2018 – 2028.

Clearances questioned

But it appears there’s no stopping the construction of the SIDC, and the buzz this has stirred on social media of the benefits it may bring.

The DPWH insists that the current alignment of the bridge is the only one that lies outside the National Integrated Protected Areas System (NIPAS).

Samal itself falls under the NIPAS Act of 1992, which preserves the island’s ecosystem and restricts certain activities to prevent environmental degradation of protected areas.

Santos said it had been officially designated as a Mangrove Swamp Forest Reserve under Presidential Proclamation No. 2152 in 1981.

To support its stance, DPWH presented documents of environmental clearances and endorsements from local government offices. These include the environmental compliance certificate (ECC) from the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) Region 11 released in December 2020.

The agency also showed endorsements from the Regional Development Council 11, from local government units (LGUs) of both Davao del Norte and Davao City, and even from the officials of Barangay Hizon along Sasa, where the bridge’s take-off point in Davao City is located.

But there are questions raised by the Rodriguezes and green groups on the clearance acquired by DENR.

In their petition, the family said the entire Samal Island is a protected area as a mangrove reserve under Proclamation No. 2152, series of 1981. They said the DPWH has not presented any legislative actions that modified Samal Island’s protected area status.

As such, any economic activity in protected areas needs to acquire a clearance from the Protected Area Management Board (PAMB), as required by the National Integrated Protected Area System (NIPAS) Act.

Such failure on the part of DPWH to acquire the clearance from PAMB should make its ECC void, the Rodriguezes’ petition said.

“Bloody” on corals

The Rodriguezes also disputed the environmental impact study (EIS) made by the DENR Region 11 last November 2021 which categorized the hard coral cover below the SIDC project as “poor.” The study claimed it only found seagrass beds and no existing coral reefs.

The family commissioned a study led by Dr. Filipina B. Sotto which showed live coral cover at the SIDC landing site between Paradise Island Park and Costa Marina Beach Resort with a “fair” category at 36.3%.

“According to the team, Paradise Reef is the worst choice for landing site in Samal due to its rich marine life,” the report stated.

Cabarde also questioned why the DENR did not include the impact on soft corals. “Soft corals are as much as valuable as hard corals are… because it’s a spawning ground for fishes,” he said.

Mitigating measures set by DPWH, including using silt curtains to catch silt spewed by the drilling of poles, do not offer assurance.

Cabarde cites the Rodriguez’s-backed study made by marine biologist Dr. John Lacson. “(He) said that the silk curtains cannot withstand the current of the Pakiputan Strait, because the current of the strait is so strong.”

“It would be bloody. It would excavate, bring out silt, bring out a lot of mud and sand. It will bring it both ways depending on the current with an estimate of seven kilometers. That would slowly sink all the way and potentially cover the reef leading to death of the corals and organisms,” Rodriguez points out.

Real consultation?

Cabarde echoes concerns from environment groups if consultations with stakeholders ever took place.

“In our talk with community people… there is no genuine consultation. It’s an FYI [for your information] session,” he said. “They were informed that the project is being constructed, but they were not consulted as to the implication of the project to the environment, the implication of the project as to the garbage that might be generated because Samal will be very much accessible to the public.”

For his part, Rodriguez recounted to newsmen in April that they were told in 2018 about the bridge project, which they welcomed. But instead of asking if parting with a portion of their property where the coral reefs were located was okay with the family, they were given three options – donate, sell, or the government will expropriate the land.

Donating was out of the question, and neither were they looking to sell. While willing to allow the use of another of their leisure properties that would have less environmental impact, the Lucas-Rodriguez clan were not really given a choice.

Cabarde believes the decision was made top-down, citing talks with regional agency heads.

“Even the regional DENR said: Our hands are tied, no one is holding back because the central office has already decided. So, first, it seems like the transaction is not transparent.”

The pro-environment Save Davao Movement (SDM) also raised questions on the transparency of government agencies in consulting with local stakeholders during the selection of the landing site.

“The SIDC’s final alignment was selected by government functionaries in an Options Selection and Scoring Workshop in Manila on 19 February 2019 without the participation of landowners and local stakeholders. Neither were landowners and local stakeholders consulted on the criteria for the selection among alternative alignments,” the group noted in a report.

Controversy surrounding CRBC

The contractor, China Road and Bridge Corporation, has been criticized for environmental and unethical practices, which should have already been a red flag.

The Georgia-based watchdog CIVIC-Idea’s China Watch report in 2021 showed that CRBC was involved in an anomalous transaction with the Philippines that led to its debarment in 2009.

It cited a JICA report that during the bidding for the Philippine National Road Improvement and Management Program (NRIMP) Phase 1, CRBC and its partner companies China State Construction Corp., China Wu Yi and China Geo-Engineering Corp. “reportedly colluded with two Philippine companies and a Korean company to set bid prices at artificial, non-competitive levels during a tender for NRIMP 1.” There were also alleged bribes given to NGOs and media to keep the matter away from the public.

The blacklist on CRBC lasted until 2017 when the Duterte administration awarded CRBC’s mother company, China Communications Construction Company Limited (CCCC), and Macroasia Corp. the Sangley Point International Airport in Cavite expansion worth $10-billion, a bidding that was reportedly criticized by national security experts and former national officials.

Cabarde also said CRBC’s Nairobi Express railway project in Kenya was criticized for cutting down 2,500 trees and displacing communities.

“If you ask the Chinese contractors, they are not really concerned about environmental sustainability. What they want is to construct some projects,” he said.

Already, environmental groups last May assailed how 223 trees were cut down near the coast of Barangay Hizon for ground preparation of the SIDC project. The area is covered by the Davao City Heritage Trees Protection Ordinance.

DPWH Region 11 spokesperson Dean Ortiz said in a press conference a month earlier that they anticipated such a scenario and are committed to plant 100 trees to replace every tree that will be cut.

But environmental groups decry that the cutting of trees violated Davao City Heritage Trees Protection Ordinance.

Davao Today obtained the contract agreement between CRBC and DPWH signed on Aug. 17, 2022.

PH-China agreement on SIDC by Verafiles Newsroom on Scribd

Japanese firms did not bid

The agreement declared that only three companies, all China-based, made the bidding for the project in 2020. These include CRBC, Hunan Road and Bridge Construction and China State Construction Engineering Corp., Ltd.

The Japanese companies that made the 2016 feasibility study on the Samal bridge construction — Katahira & Engineers International, Nippon Engineering Consultants Co., Ltd. And Nippon Steel & Sumitomo Metal Corporation— were not mentioned by DPWH to have made a bid for the project.

CRBC and Hunan passed the first stage of evaluation in September 2020, and CRBC ultimately was found eligible for the project in the final evaluation in December 2020.

The contract stipulated that CRBC will be “liable for any damages or defects discovered on the works due to faulty construction or the use of materials of inferior quality or violation of terms of the contract” within one year after completion of the SIDC bridge.

A third-party monitoring is stipulated in the contract, handled by the Independent Checking Engineer (ICE) sub-consultant: China Railway Major Bridge Reconnaissance and Design Institute Co., Ltd. (BRDI).

Cabarde said Ateneo de Davao has expressed to DENR its interest to be part of the monitoring team, but has not been invited.

“We need [the] academe to be the science of the project, to monitor the destruction or the implication of possible destruction along the way in their construction. We have talked to Secretary (Maria Antonia Yulo) Loyzaga of DENR and she’s the one who insisted,” he said.

“We insist [on] putting some legal safeguards. That is very crucial in order to prevent such imbalances in the environment and in the economic development of some,” Cabarde added.

Legal options

Aside from these actions, environmental groups have considered filing a Writ of Kalikasan at the Supreme Court.

The writ is a special remedy made by the Supreme Court, consistent with the provision in Section 16, Article 2 of the 1987 Constitution. It is used in cases where there are supposed violations against the people’s constitutional right “to a balanced and healthful ecology in accord with the rhythm and harmony of nature.”

Cabarde said officials are also liable under the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act (RA 3019) or the Code of Conduct of Public Officials for lack of transparency in engaging the public on the SIDC issue.

Saving the reef won’t stop

But the environmental groups and the Rodriguezes know time and public opinion are not on their side. But they will not stop for the sake of saving the reef.

The Costa Marina Resort no longer accepts visitors as the humongous end of the craneway stands in the middle of their shoreline.

A hundred meters away from Costa Marina, guests of Paradise Resort could hear the constant drilling and booming noises from the construction, disturbing their time at the beach.

“Para na rin tayong naliligo sa ilalim ng tulay,” a visitor exclaimed. (It’s like we’re swimming under the bridge)

Cabarde said Davawenyos should weigh in on the benefits of a bridge that may shorten travel time to beach resorts but also shorten the life of corals and marine life.

He said ₱19-billion of the project cost is loaned and, as a taxpayer, he will pay for it and, in effect, contribute to the cost of destroying the marine ecosystem, corals and the marine protected area.

“I don’t think we can sleep soundly at night knowing that.”

- With reports from Valerie Joyce Nuval, VERA Files

This story was produced in partnership with Davao Today with support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.