Documents circulating online that purport to expose a $100 billion money laundering scheme involving the Marcos family’s supposed 350 metric tons of gold are riddled with red flags. These include references to fictitious banks, dubious account numbers, and formatting anomalies inconsistent with how illicit wealth is typically hidden.

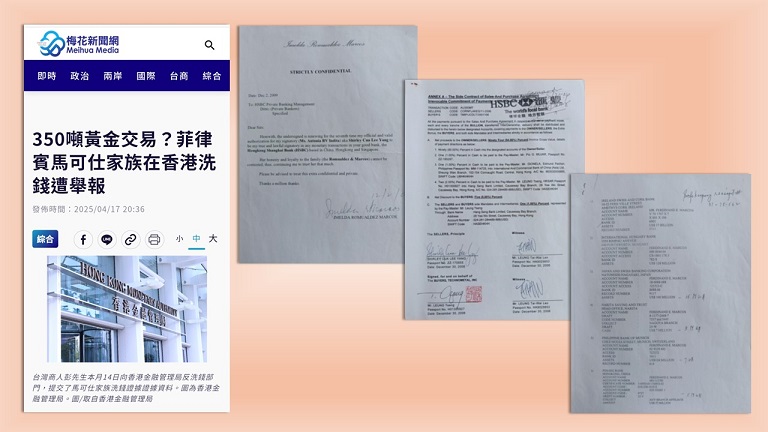

Screenshots of the alleged documents accompanied a report that first surfaced in mid-April in Taiwan, claiming that Imelda Marcos, the widow of ousted president Ferdinand Marcos Sr., sold the gold in Europe and the United States and funneled the proceeds through 18 bank accounts, reportedly worth over $100 billion, with the help of a Hong Kong-based bank.

The report also alleges that the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) is investigating the scheme, allegedly based on documents submitted to its anti-money laundering division by a Taiwanese businessman identified only by the surname Peng.

The story has since gone viral on Chinese online platforms and has been amplified in the Philippines by supporters of detained former president Rodrigo Duterte, including vlogger Claire Eden Contreras (aka Maharlika) and lawyer Harry Roque. Both have used the allegations to again attack President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. and revive rumors about his alleged drug use.

The HKMA has not issued a public statement on the allegations. In response to this writer’s query, the agency said it does not comment on individual cases.

“In line with international standards, banks in Hong Kong are required to implement effective anti-money laundering and counter-financing of terrorism systems, taking into account their risk appetites and business operations,” the HKMA said. “Where banks identify any suspicious transactions, they are required to report to law enforcement agencies as soon as practicable for investigation and follow-up.”

The HKMA added: “It is worth noting that the investigation of crimes, as well as the tracing, restricting and confiscation of funds or property concerned, is carried out by law enforcement agencies in accordance with relevant laws and regulations in Hong Kong (e.g., the Organized and Serious Crimes Ordinance).”

The report emerged as the Philippines heads into a tense election season, marked by deepening fractures between the Marcos and Duterte factions. Its circulation came after the March 11 arrest of former president Rodrigo Duterte, now detained in The Hague and facing trial before the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity tied to his brutal war on drugs.

Chinese commentaries have framed the situation as a “Jedi counterattack,” a veiled reference to Duterte’s resilience. Some have speculated without proof that Duterte laid the groundwork for the revelations during a visit to Hong Kong just before his arrest.

The narrative has also been linked to rising tensions between the Philippines and China over the West Philippine Sea. The report’s timing coincided with the annual Balikatan joint military exercises between the Philippines and the U.S., which Beijing has criticized.

According to the viral story, Peng claimed that between 2006 and 2011, Imelda Marcos authorized a housekeeper—identified in the documents as Antonia RV Indita, also known as Shirley Cua Lee Yang—to use shell companies to sell the 350 tons of gold and route the proceeds through HSBC in Hong Kong. The destination of the funds remains unclear.

Peng reportedly said he was one of a dozen intermediaries from the United States, Australia, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and the Philippines who helped facilitate the transactions. He also alleged that the Marcos family had held vast quantities of gold since the 1990s.

The 350 tons of gold cited in the report far exceed the Philippines’ official reserves. As of December 2024, the Philippines recorded 130.89 tons, valued by the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas at $12.05 billion in February.

The banks that don’t exist

Many of the financial institutions listed in the partial bank roster supposedly submitted by Peng to the HKMA appear to be fictitious.

Among the most glaring is a supposed “Philippine Bank of Munich” located on Chez Mouia Street in Munich, Switzerland. No such street exists, and no city or canton in Switzerland is called Munich. Munich is a city in Germany.

Ruben Carranza, former commissioner of the Presidential Commission on Good Government who led efforts that recovered $680 million in Marcos assets hidden in Switzerland, the U.S. and other countries, said no such bank exists in Germany either.

“It would be such an incredible thing for any Filipino to have a bank in Europe…given the reserve requirements in the European banking system,” he said.

The alleged document also lists institutions such as the “Ireland Swiss and Cork Bank” and “International Hungary Bank,” neither of which appears in official registries of licensed financial institutions.

Other details raise additional suspicion. “Fern Ville”, a supposed street in Cork, Ireland—the supposed location of the Ireland Swiss and Cork Bank—is not a street but the name of a two-story home built in Cork, Ireland’s second largest city, in the 1800s, as confirmed by search engine results and online mapping tools.

A search for “Rimpau Ave” in “Forthworth, Hungary,” the claimed address of the International Hungary Bank, leads nowhere. There is no city named Forthworth in Hungary.

Account numbers appearing in the alleged document also do not conform to the standard structure of the banking systems in the countries that were listed.

There are no records of banks named “Japan and Swiss Banking Corporation” or “Narita Saving and Trust” operating in Japan. “Natomishi-Nagasaki,” the listed location of the Japan Swiss and Banking Corporation, does not correspond to any known city, town or district in Japan.

The same bank names appear in another unrelated document: a purported deed of assignment dated Sept. 6, 1985, allegedly executed by then president Ferdinand Marcos Sr. and Fr. Jose Antonio M. Diaz. It claims the pair assigned their rights over $500 billion in cash and gold deposits in 15 Japanese banks to a Rev. Dr. Floro E. Garcia.

That document also contains numerous red flags: fabricated bank names and misspelled details. The accounts are supposedly under the name of Diaz or one of his nine alleged aliases.

Supporters of the late dictator have long tried to rationalize the Marcos family’s unexplained wealth, claiming the so-called Tallano royal family paid Marcos and Diaz 400,000 tons of gold for legal services, a myth that has been repeatedly debunked by historians. Imelda Marcos has also attributed her husband’s fortune to gold he allegedly found after World War II, often linked to the mythical Yamashita treasure.

During the 2022 presidential campaign, Ferdinand Marcos Jr. denied the existence of either treasure, saying he had seen neither.

Sloppy and suspicious

Carranza described the alleged documents cited by the latest report on the purported transactions involving the Marcos family’s alleged 350 tons of gold as “sloppy” and “suspicious on many levels.”

The listings name Ferdinand E. Marcos as the direct account holder, a move Carranza said contradicts how the family historically concealed wealth.

“Why would Ferdinand Marcos open a bank account in his name? In all the Swiss bank accounts that we’ve uncovered and some of which we recovered, you’ll never see Ferdinand Marcos as the account owner,” he said.

Instead, the Marcoses used layered institutions and trusted agents to obscure ownership and complicate asset recovery efforts.

One screenshot in the viral report shows a letterhead with the signature of “Imelda R. Marcos” authorizing a house help to transact on her behalf. Another document contains grammatical errors and inconsistent formatting.

“No one would take you seriously,” said Carranza, noting that the Marcoses typically hired experienced bankers and lawyers to manage their finances discreetly. They included Swiss banker Bruno de Preux.

He added that financial criminals, including scammers, rarely broadcast their schemes in public.

“If this person wanted money from the Marcoses, he would’ve approached them directly and said something like, ‘I’m going to blackmail you,’” he said. “But this report was circulated publicly, almost like a press release…It’s suspicious on many levels.”

Carranza noted that while Hong Kong was used in the past by the Marcoses for illicit financial activity, those operations were deeply covert and routed through professional intermediaries, not anonymous online uploads. “This story is different because it doesn’t fit that pattern,” he said.

He cited a historical example: kickbacks Ferdinand Marcos Sr. received from Japan’s war reparations. A year after becoming president in 1965, Marcos began channeling the reparations program toward the public sector, manipulating it to extract 15% “rebates” or kickbacks and earning him the moniker “Mr. 15 Percent.”

According to Carranza, the operation was facilitated by retired Brig. Gen. Eulogio Balao, then chair of the war reparations committee, who routed the funds through Hong Kong before transferring them to Marcos’ Swiss accounts.

An affidavit submitted to the PCGG by Balao’s successor, former Public Works Minister Baltazar Aquino, said the scheme generated at least $47.7 million in kickbacks between 1966 and 1971.

Even while court cases were pending, Imelda Marcos traveled to Hong Kong or Shanghai under the guise of seeking traditional medicine but would meet her American lawyers, including James Linn, Carranza said.

Following the story trail

The viral claim about the Marcos family’s alleged sale and laundering of 350 tons of gold first appeared on Chinese-language websites in Taiwan. One of the earliest outlets to carry the story was Meihua Media, a site viewed by some as pro-China due to its owner’s and editors’ stance on reunification.

Published on April 17, Meihua Media’s report spread across not only Taiwan but also overseas Chinese communities through websites, some of them registered in China. For example, Taiguo.com (Thailand Network), which pushed the narrative to a Thai audience, lists Shanxi province as its registrant location, while Huaren Zhan lists Shandong.

The narrative also reached Chinese-speaking communities in the Philippines or those following developments there via Fei Hua Ba (Philippine Chinese) on Weixin and through sites like Phhua.com and Bole.ph.

Asia Television News (ATV), a company registered in Kuala Lumpur with a website hosted in Hong Kong, republished the story on April 28. ATV’s report was heavily cited by Chinese-language social media accounts, helping the claim gain momentum in China.

By April 29 and 30, the story had been adapted into text and video content and shared across hundreds of accounts on major platforms: news aggregators and portal iFeng, Sohu, NetEase, Toutiao and Baidu Bajiahao; video platforms iQIYI, Haokan Video and Bilibili; social media platforms WeChat, Weibo and Douyin; and messaging platform QQ.

A short video version of the story began circulating on Philippine Facebook pages after Russia Today posted it on Weibo, drawing more than 230,000 plays. China VTV of Hong Kong later reposted it on Facebook.

Among the pro-Duterte pages and groups that amplified the video were Gringo ICC Petition, Du34s, Duterte Seafarer’s Club and PRRD–The Greatest, one of whose page administrators is listed as based in China.

China Youth Daily, the official newspaper of the Communist Youth League of China, posted the video on TikTok on April 30, helping it reach audiences outside China. TikTok does not operate in China.

On X (formerly Twitter), English-language versions appeared through accounts like ShanghaiEye, affiliated with the state-owned Shanghai Media Group, and a newly created pro-Duterte account named Taylor Cayetano. These posts helped spread the claim beyond Chinese-language circles.

Several English-language Facebook accounts echoed the narrative using content posted by Asia Today, a self-described news page linking to a questionable website.

The story gained further traction in the Philippines on Labor Day when Roque and Contreras repeated the allegations in video posts. These were picked up by Bombo Radyo, Politiko and Abogado. Contreras posted a follow-up video on May 2.

On Philippine social media, reactions were sharply divided. Some mocked the Marcos family, others expressed outrage at its lack of media coverage, and a few treated it as part of a supposed Duterte counterattack.

Falling for the lie – over and over

Carranza said the reemergence of the Marcos gold narrative serves to manufacture legitimacy and obscure historical accountability.

Despite rulings by Philippine and foreign courts declaring the family’s wealth illegal, he said the Marcoses have continued pushing the idea that their riches stem from gold—not corruption.

The former PCGG commissioner lamented that many Filipinos continue to fall for the myth, with scammers exploiting it to solicit payments from people hoping to claim a “share” of the Marcos gold.

“But you see Bongbong Marcos laugh it off on TV, saying, ‘I don’t know about that.’ if you didn’t and they’re using your name, shouldn’t you ask them to be investigated?” Carranza said, referring to Ferdinand Marcos Jr. “This is syndicated estafa.”

He said the Marcoses are avoiding an inquiry that would open up a deeper discussion into the crimes they committed.

Carranza also said that while the Marcoses and Dutertes have been attacking each other over a range of issues, they have stayed away from exposing transactions and specific acts of corruption that would implicate not only themselves but also their allies and cronies whose support they need, especially in the 2028 presidential elections.

On why the myth of the Marcos gold persists, Carranza recalled a theory once shared by the late PCGG Chairperson Hayee Yorac.

“She would always say that the Marcoses wanted to exaggerate, and even just create these myths about having gold,” he said. “That was just the way for them to cover up their stealing. So, for (anyone) to take that seriously would precisely fall into the trap laid out by the Marcoses.”

(Yvonne T. Chua is an associate professor of journalism at the University of the Philippines Diliman and the project coordinator of Tsek.ph.)