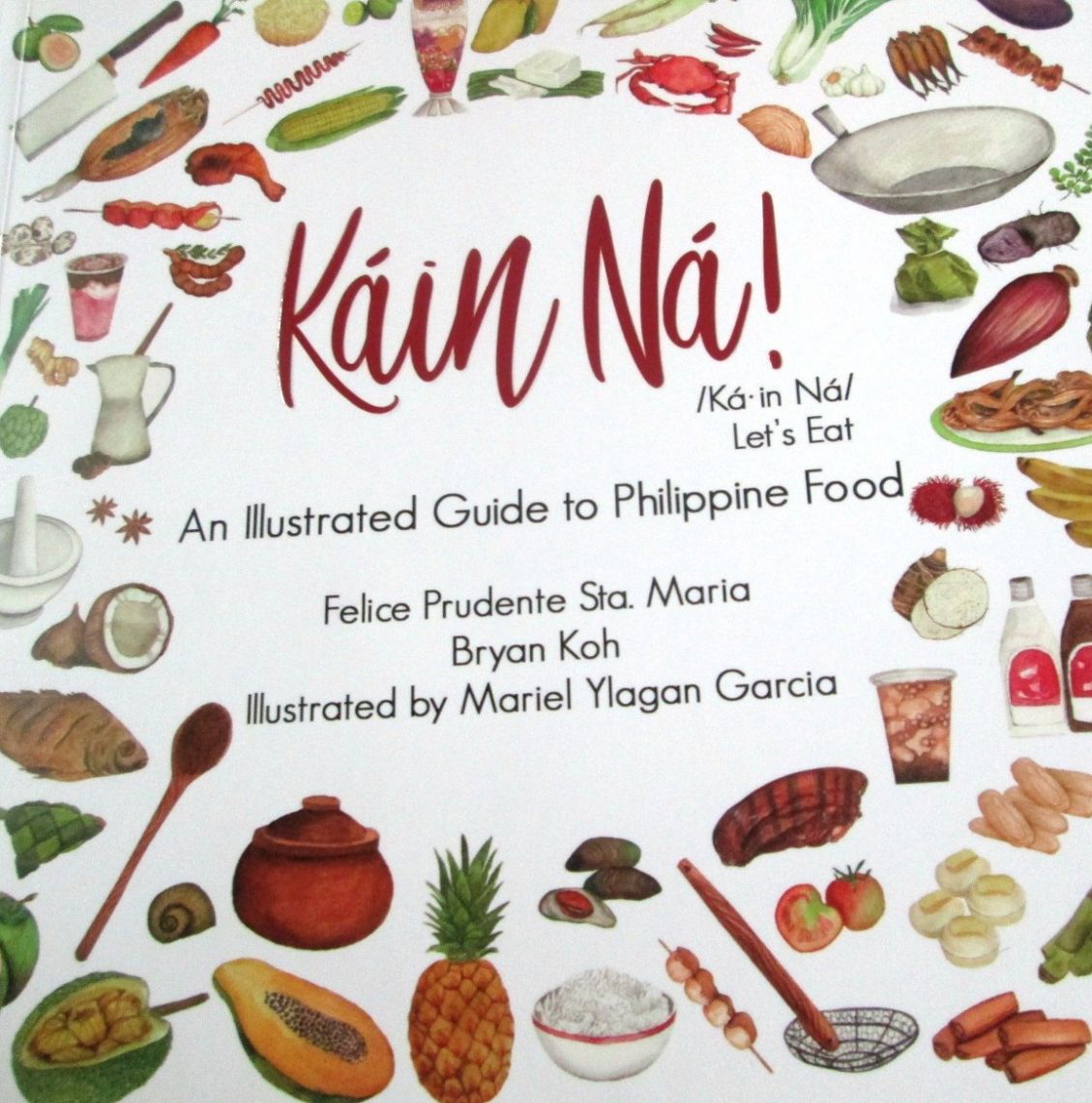

After the ground-breaking Kulinarya: A Guidebook to Philippine Cuisine by Glenda R. Barretto et al, many cookbooks have since been published but none as portable, as informative and as colorfully and prettily illustrated as the newly released Kain Na! An Illustrated Guide to Philippine Food.

Co-authored by veteran food writers Felice Prudente Sta. Maria and Bryan Koh with illustrations of ingredients and dishes north to south of the archipelago rendered in watercolor by Mariel Ylagan Garcia, Kain Na! opens with the premise that “Philippine cuisine is like no other.” The country has absorbed the food and preparation methods not only from neighboring mainland Asia but also especially from the Spanish and American colonizers.

Food is one big “quest for abundant deliciousness.” This is evident in the festive colors (gold and red) in both Christian and Muslim communities—the Maguindanao’s use of turmeric yellow rice which symbolizes royalty. The Christian fiesta is also a chockfull of colors—e.g. rellenos or forcemeats carry the different flavors of green olives, hardboiled eggs, ham, sausages, dark raisins, among others.

The book, an RPD Publications title, is divided into Almusal or breakfast, Lutong Bahay or home cooking, Meryenda or snacks, Lutong Kalsada (street food), Panghimagas (dessert), pulutan (beer chow), Pang-pista (fiesta fare), Inumin (beverage), Sa Panaderya (in the bakery), Kakanin or native delicacies, Mga Sawsawan (dipping sauces) and Mga Sangkap (ingredients).

Other books may concentrate on influential Tagalog, particularly Cavite, and Kapampangan food. But this one acknowledges the contributions of our Muslim brethren like the Tausug morning meal called maginum. It is composed of bangbang sug (rice cakes) paired with satti ayam (grilled chicken with a sweet and spicy sauce).

Another Tausug breakfast food is the junay, made of banana leaf parcels filled with raw rice mixed with oil, salt and a paste of siyunog lahing (pounded coconut that is roasted until it’s burnt).

The Cebuano balbacua (found in other parts of the Visayas) is similarly included. One wonders if this is their version of the kare-kare of Luzon because the recipe also calls for the use of oxtail, roasted peanuts to thicken the sauce and annatto for coloring. But instead of pairing it with unlimited rice, balbacua is best enjoyed with bugas na mais or corn grits.

Listed as Lutong Bahay is the Tausug tiyula itum which is described as “boiled beef made fragrant with lemongrass. It employs sunog lahing, the burnt coconut paste that makes both the broth and the meat itum or black.” This is served on special occasions like after Ramadan.

Favorite meat dishes like humba, lechon kawali, Quezon’s jardinera, binagoongang baboy estofado and what gourmet and dean of food writers Doreen G. Fernandez, an English professor, called the grammatically incorrect crispy pata all have their pride of place in the pages as do the humble Ilokano dinengdeng, poqui-poqui and dinakdakan.

The authors contend that the meryenda or afternoon snack “is a must in the Philippines. Some of the most interesting, provincially diverse and delicious foods are served as pantawid gutom, meaning to ‘bridge the hunger gap’ between lunch and dinner. One can survive eating just merienda fare.”

Common merienda are noodles because they are filling—from pansit palabok to pansit Canton to pansit mami to Cavite’s pansit choco en su tinta (blackened by ink from squid) to pansit habhab of Lucban, Quezon. Also popular are the ensaymada, empanada kaliskis, empanada Vigan, which can now also be found outside the Ilocos province, lumpiyang ubod, dinuguan, tamales, ginataang halo-halo and bibingka.

The range of Lutong Kalsada is just as wide or as many as the piers, parking lots, churchyards, town plazas, well-trod lanes and bus terminals dotting the country. What binds food from balut to binatog is their affordability and accessibility

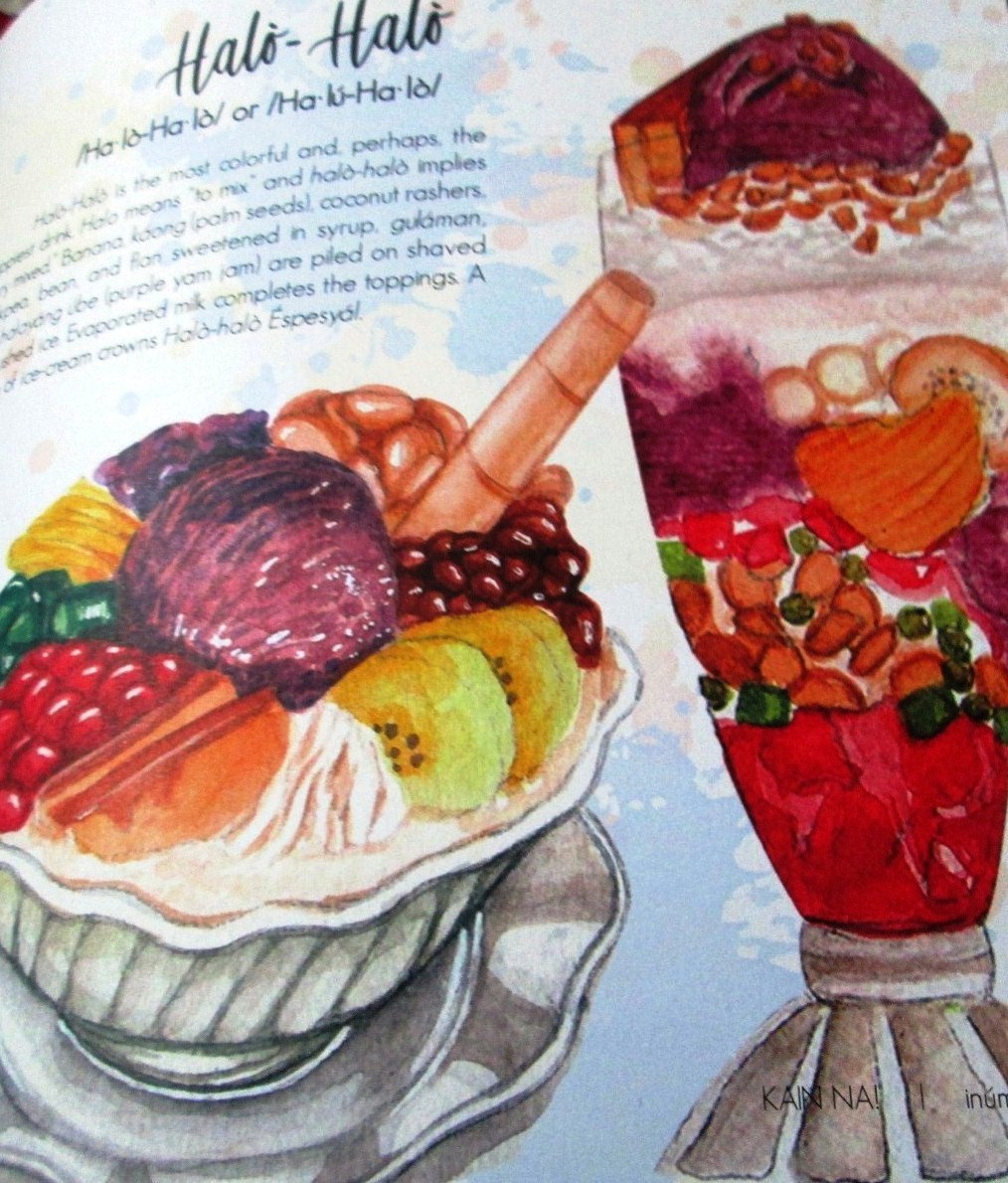

Panghimagas is derived from an old Tagalog word, himagas, which means “to eat sweets at the end of the meal. It implies that the favored flavor to have lingering after a Philippine meal should be sweetish to saccharine.” These desserts can be anything from fresh fruits to complex ones like cakes, fancy meringues and ice cream. The authors note that “giving desserts flair, fancy and flavor is very competitive whether at food floors in malls or top-tier establishments.”

They also cannot trace the identity of Mercedes in brazo de Mercedes. All they can do is poetically describe it as “a romance of egg whites turned into light fragility partnered with a silken, golden, egg-rich, vanilla custard.”

Pulutan or drinking foods can be anywhere from the lowly dilis to the more elaborate nogada de pagi which is traced to San Roque, Cavite. It is made up of pagi (stingray) cooked with beer, miso quesillo (carabao milk cheese), salted duck egg and wansuy (native coriander). Nogada is Spanish for walnut tree. This sounds like a whole viand in itself.