By CAROLYN MERCADO and STEVEN ROOD

By CAROLYN MERCADO and STEVEN ROOD

THE Philippine Judiciary is on edge. Five months of rigorous scrutiny by the public and media as a result of the trial of impeached Chief Justice Renato Corona created a high degree of expectation that major reforms are forthcoming. Ensuring that Corona’s conviction and the appointment of a new chief justice will lead to a lasting improvement of the country’s judicial system is putting tremendous pressure on the high court.

![]() Often lambasted as dysfunctional, the judiciary has long been a natural target for those wanting to strengthen institutions in this developing country. Beginning in 1998 with the Blueprint of Action for Judicial Reform, a series of diagnostic studies on the justice system established basic data that provided the rationale for the proposed investments for the Judiciary. The Blueprint also provided the basis for the development of concrete projects and activities that resulted in the Action Plan for Judicial Reform (APJR).

Often lambasted as dysfunctional, the judiciary has long been a natural target for those wanting to strengthen institutions in this developing country. Beginning in 1998 with the Blueprint of Action for Judicial Reform, a series of diagnostic studies on the justice system established basic data that provided the rationale for the proposed investments for the Judiciary. The Blueprint also provided the basis for the development of concrete projects and activities that resulted in the Action Plan for Judicial Reform (APJR).

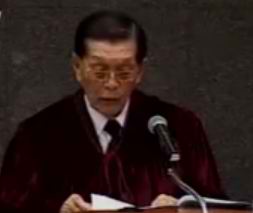

Under the leadership of Chief Justice Hilario Davide, Jr., the APJR was enunciated in the “Davide Watch” that summarized the vision of the Philippine Judiciary as: “A Judiciary that is independent, effective and efficient, and worthy of public trust and confidence; and a legal profession that provides quality, ethical, accessible and cost-effective legal service to our people and is willing and able to answer the call to public service.” The Davide Watch became the official mantra of the more than 1,700 courts throughout the country. The APJR was responsible for the establishment of the Court Administration Management Information System which provided a database of all cases in the first and second level courts; the Justice on Wheels as an access to justice initiative to reach areas where there are no courts; an electronic judicial library that provided 24-hour access to jurisprudence; court-annexed mediation and judicial dispute resolution that provided options to litigants to avoid long and piecemeal trials, among others.

When Chief Justice Davide reached the mandatory retirement age of 70 in December 2005, his ally, Artemio Panganiban, followed suit. As the new chief justice, perhaps because of his private sector experience, Panganiban reframed the Davide Watch into his own vision of “Liberty and Prosperity.” It was short lived – he served for only one year until his retirement in December 2006.

The next chief justice, Reynato Puno, had a somewhat different take on what was needed, and instituted substantive legal reforms like the writ of amparo [a dream of Justice Adolf Azcuna, now chancellor of the Philippine Judicial Academy], writ of habeas data, and writ of Kalikasan (environmental writ). The writs are special remedies available to any person (natural or juridical) whose right to life, liberty, and security (or health in the case of the environmental writ) is violated or threatened with violation by an unlawful act or omission of a public official or employee or private individual or entity. Chief Justice Puno championed human rights at a time when extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances were at their height. He formed a “conspiracy of hope” where the Supreme Court became the sanctuary of human rights victims and advocates. He served for four years until he retired in May 2010.

Renato Corona, who succeeded him as chief justice, was embattled from the start. His midnight appointment by then outgoing President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo (GMA) was marred in controversy since the president was barred by the 1987 Philippine Constitution to make an appointment two months immediately preceding a presidential election.

However, the Philippine Supreme Court, characterized as a GMA court because more than half of the sitting justices were her appointees, ruled that the appointment was legal. Despite this, the legitimacy of his appointment always haunted Corona. The newly elected president in 2010, Benigno Aquino III, refused to take his oath of office before Corona, and instead took his oath before Justice Conchita Carpio-Morales, now the ombudsman.

In his two years as chief justice, Corona’s vision for the judiciary never saw a clear articulation – though he did some pilot docket cleansing and case decongestion in some pilot courts in Metro Manila.

So, what does this mean for the future? Without the benefit of a crystal ball, one thing we know is that we cannot squander this golden opportunity to collectively rebuild our battered and weakened judicial institution. For one, we need a leader with a vision who can shepherd the judicial system into a new era of public management focused on “customer” needs and with accountability for results; genuine judicial independence that is not afraid of transparency, particularly in resource allocation and results; fairness and equality in decision-making; decentralized control through a wide variety of service delivery mechanisms such as the adoption of a regional court administration office; and an integrity infrastructure system that will strictly implement the Code of Ethics.

There is a lot to be done to improve the judicial system in the Philippines. But first, because institutions are only as good as the people who run them, we need to ensure that the next chief justice is a person of integrity, competence, and independence, with a vision to carry out genuine transformation of the institution. Most importantly, the next chief justice needs to be someone who will be able to unite a woefully divided court.

(Carolyn Mercado directs The Asia Foundation’s Law and Human Rights program in the Philippines and Steven Rood is the Foundation’s country representative in the Philippines. The views and opinions expressed here are not those of The Asia Foundation.)