Why do we love pork so much? Pork is the most consumed meat in the country; as of 2022, pork per capita consumption is 15.32 kilos. Some favorite pork dishes include adobo, longganisa, grilled liempo, barbecue, sisig, crispy pata, or menudo. And the hard-to-resist chicharron.

A familiar scene in Philippine life— raising pigs in the backyard remains a common preoccupation, literally a piggy bank for rainy days, with neighbors collecting leftovers as pig food. Familiar too are pig’s negative associations: obesity, gluttony, filth, or greed.

Foodways

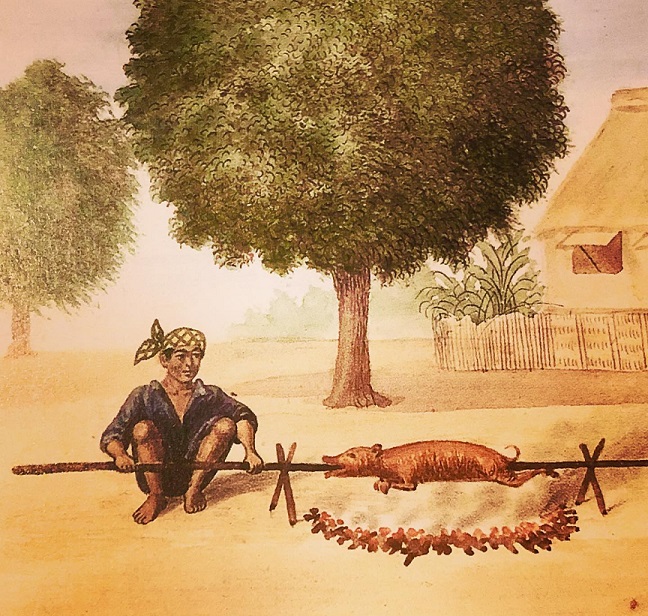

Antonio Pigafetta, the Venetian chronicler of Ferdinand Magellan’s expedition in 1521, wrote the first published description of food in the archipelago. In the Visayas, Pigafetta and company feasted on pork with its broth, roast pork, and fish. On Easter Sunday, the local chiefs presented two pigs to Magellan’s crew.

Pigafetta also observed that Cebuanos raised pigs, goats, and chicken under their houses. He described how pigs were consecrated in sacrificial rituals. Two old women danced around the pig, pouring wine, and thrusted a lance into the pig’s heart and body. Then, they marked the foreheads of the locals present in the ceremony with pig’s blood. The pig was cooked and served in dishes.

In Spanish Manila, a Chinese market located outside Intramuros sold all kinds of food, including Chinese ham, bacon, and salted pork. Imported ham from the United States, England, Spain, and Australia were also available in Manila’s comestibles or grocery stores in the 19th century.

Many of today’s pork dishes serve during special occasions can be traced to the Spanish colonial period. Noche Buena, notes Doreen G. Fernandez, is a time for eating hamon, morcon, embutido, and good old lechon.

Archaeology

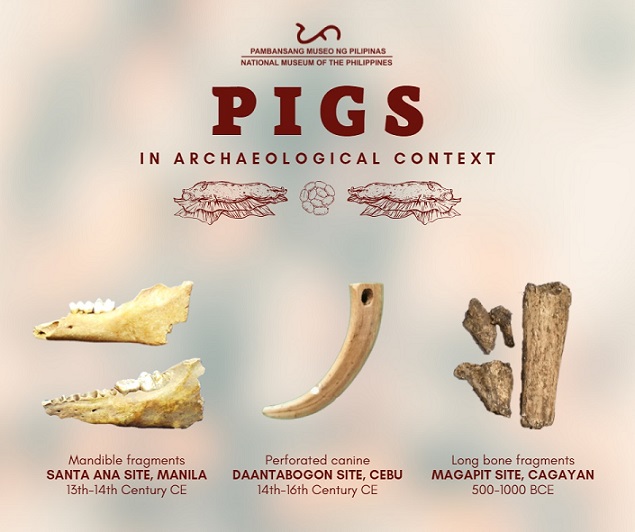

The earliest evidence of domestic pigs in the country comes from Nagsabaran, Cagayan dated 4000 Before Present (BP). Excavated bones of domesticated and wild pigs in Batanes, Bohol, and Palawan reflect the pig’s long and deep relationship with early Filipinos.

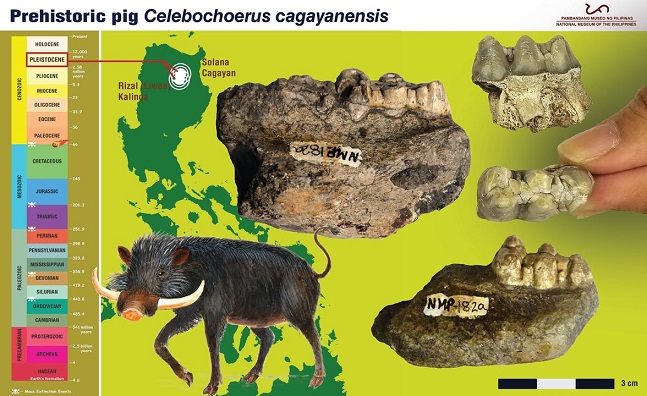

A giant species of pigs lived some 800,000 years ago (Middle Pleistocene); teeth fossils of the extinct species were discovered in Rizal, Kalinga in 1971 and Solana, Cagayan in 1978.

Modified pig bones in Leta-Leta Cave in Palawan suggested other uses, aside from food. Shaped like daggers with a hole at one end, the bones could have been used as implements or pendants. Pigs’ teeth as necklaces; boar tusks as ornaments or charms are used by the Ilongot and Ifugao.

Rituals and beliefs

Pigs were used in rituals and as ornaments and charms as early as 500 BCE. Many ethnolinguistic groups view pigs as the link between humans and the spirit world. Specifically, domestic pigs are kept and raised for rituals and ceremonies since ancient times; wild pigs are hunted for subsistence. An Ifugao mumbaki, a Benguet mambunong, or a babaylan folk healer interprets the pig’s bile sac, liver, or gall bladder for auspicious signs or warnings for the community.

The ritual sacrifice to appease spirits is a part of ritual feasting. The quantity and quality of pigs offered reflect the feast sponsor’s social status, wealth, and power. Distribution of meat to participants also reflect their status and relationship with the sponsor.

Ifugao life is marked by rituals during birth, marriage, sickness, or death with pig as the sacrifice animal. Representing wealth and prestige, pigs are offered as bride wealth, to acquire land, or to strengthen and solidify social and political alliances.

The Ifugao follow an elaborate and prescribed system of meat distribution with regards to specific cuts of raw meat, quantity, and to whom it is given. Ifugao, Agta, and Ilongot dwellings display pig skulls and mandibles to express their status.

In a research paper on the role of native pigs in Ifugao feasting and socio-political organization (2017), Q. Lapeña and S. Acabado have argued that the intensification of ritual feasting in the Old Kiyanggan Village during the Spanish period resulted in “the consolidation of political and economic resources” that consequently led to Ifugao’s “successful resistance against Spanish conquest.”

The Tau-Buhid, a Mangyan community in Mindoro, believe that pigs represent their physical connection with spirits. Ritual hunting serves as a bridge between the physical world and the spirit world and pig sacrifice is nonnegotiable. Having a good relationship with the spirit world, they can maintain community harmony.

The Ibaloy of Upper Loacan, Benguet also regards pigs as “connectors” to spirits of the dead, ancestral spirits, and the living.

From the Hiligaynon word “paghidaet” or peace, the Pana-et ritual is enacted every seven years on Good Friday in Tubungan, Iloilo where babaylanes from Panay and Negros converge to pray for good weather and harvest. First recorded in 1847, it is a ritual of lamentations, thanksgiving, prayers, and peace offerings to spirits. A feast follows, serving freshly-slaughtered native pig, shrimps and crabs, rice cakes, and other delicacies.

Wild pigs

Today, the country has four endemic species of wild pigs, all endangered. The Visayan warty pig is found in Panay, Negros, and Cebu; the Oliver’s warty pig in Mindoro; Philippine warty pig in Luzon and Mindanao; and Palawan bearded pig in Palawan.