(Second of two parts)

Ten years ago, a “dream plan” for an interconnected Mega Manila was born: no traffic congestion, no households in hazardous areas, no barriers to mobility, no burden for low-income groups and no air pollution.

The Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) devised a roadmap for a 318-kilometer transit network with the North-South Commuter Railway (NSCR) as its “backbone.”

This dream plan grew legs when the Philippine government, under the Duterte administration, picked Japan Overseas Infrastructure Investment Corporation for Transport and Urban Development (JOIN) to conduct the partial feasibility study over China, which also expressed interest in the same endeavor.

(Read Faulty land survey derails right-of-way, relocation for Malolos-Clark Railway)

During the official loan signing for the first tranche of the MCRP’s loan agreement with ADB, Duterte bragged: “The 53-kilometer Malolos-Clark Railway Project or the MCRP… will be the country’s first airport express railway service.”

“Sa part naman ni [San Fernando] city, gusto namin ma-experience ‘yung train. Imagine you can go to Divisoria in a matter of 45 minutes kung maganda ‘yung access namin sa mga main commercial districts ng Metro Manila,” said Paolo Franco, head of the San Fernando City Planning and Development Office (CPDO), in an interview with VERA Files on Oct. 2.

(On the part of the city, we want to experience the train. Imagine, we can go to Divisoria in a matter of 45 minutes if we have good access to the main commercial districts of Metro Manila)

The Malolos-Clark segment of the NSCR includes a 1.90-kilometer (km) link to the existing Blumentritt station in Manila, with a connection to the elevated Light Rail Transit-1 line. The other segments of the 163-km commuter line is the 38-km Malolos-Tutuban line and the 55-km southern corridor from Blumentritt to Calamba City.

When Franco joined the city government of San Fernando in 2022, initial projections for the MCRP completion were slated for 2027. After a year in the job, he said this was moved to 2028 and, in their recent local inter-agency committee (LIAC) meeting, this was again pushed back to 2029.

“Ang mahirap lang talaga in reality is the process of DOTr, ang bagal. The bureaucratic delays sa pag-award ng properties or finishing the legalities of this relocation, ang bagal nila,” he said.

(What is really difficult in reality is the process of DOTr, it’s too slow. The bureaucratic delays in awarding properties or finishing the legalities of this relocation, they are slow.)

Franco said the LIAC meets once every three months to address concerns of right-of-way (ROW) acquisition and compensation of their relocatees. LIAC is the central decision-making, coordinating and consultative body for the resettlement of informal settler families (ISFs).

Data from the National Housing Authority obtained by VERA Files shows that less than 6% of ISFs in Pampanga province alone have been verified and relocated as of September 2024.

The process with ISFs “should be faster” since they are not property owners, Franco said, but what takes a lot of time is the building of ready-to-occupy houses.

“Dapat well-built na ang bahay, na-develop na ang lugar. Meron nang mga services doon, tubig, kuryente, tapos na-clear na lahat… as in meron na siyang occupancy permit from the LGU,” he explained.

(The houses should already be well-built, the place should already be developed. There should be services there – water, electricity. And everything should be cleared, including an occupancy permit from the [local government unit].)

Without these prerequisites, the demolition of houses along the main railway line cannot proceed.

San Fernando has 67 row houses built and occupied in Barangay Calulut as of October 2024, while 312 housing units in Barangay Panipuan are ready for occupancy.

Another site in Barangay Panipuan on the side of Mexico town would have 280 units in four low-rise buildings, but this has not started construction due to a land reclassification issue. Previously classified as a Strategic Agriculture and Fisheries Development Zone (SAFDZ), the land had to be converted for residential development.

A SAFDZ refers to “prime” accessible and strategic lands within a locality dedicated for active agricultural and fishery production. These ideally showcase modern farming and fishing technologies and come with accessible and available supporting facilities.

SAFDZs form part of the country’s network of protected areas for agriculture and agro-development, identified by the Department of Agriculture (DA) and validated by LGUs.

Conversion of SAFDZ to land for housing projects is allowed, based on DA rules.

“It could have been prevented prior to the purchase of the land. Sana nagtanong sila sa LGU ano ba ‘yung classification niyan,” Franco pointed out.

(They could have asked the LGU about the land’s classification.)

Nilda Quito, head of Angeles CPDO and engineer by trade, lamented DOTr’s lacking effort to provide the LGU with a copy of parcellary maps that shows the affected areas and structures of the MCRP in the city.

In turn, this strained the LGUs from exercising their mandate to grant new building permits to potential business owners in the area.

“Doon talaga importante ‘yung parcellary plan… lalo na ‘pag may mga kumukuha ng mga building permits which is malapit sa riles din,” said Quito in an interview with VERA Files.

(That’s really where the importance of the parcellary plan comes in… especially if there are applications for building permits near the railway).

She said obtaining parcellary plans and alignment would ease the information flow and improve coordination with building permit applicants because the LGU would be able to identify the exact square meters of the land that would be affected by a big-ticket infrastructure project such as the MCRP.

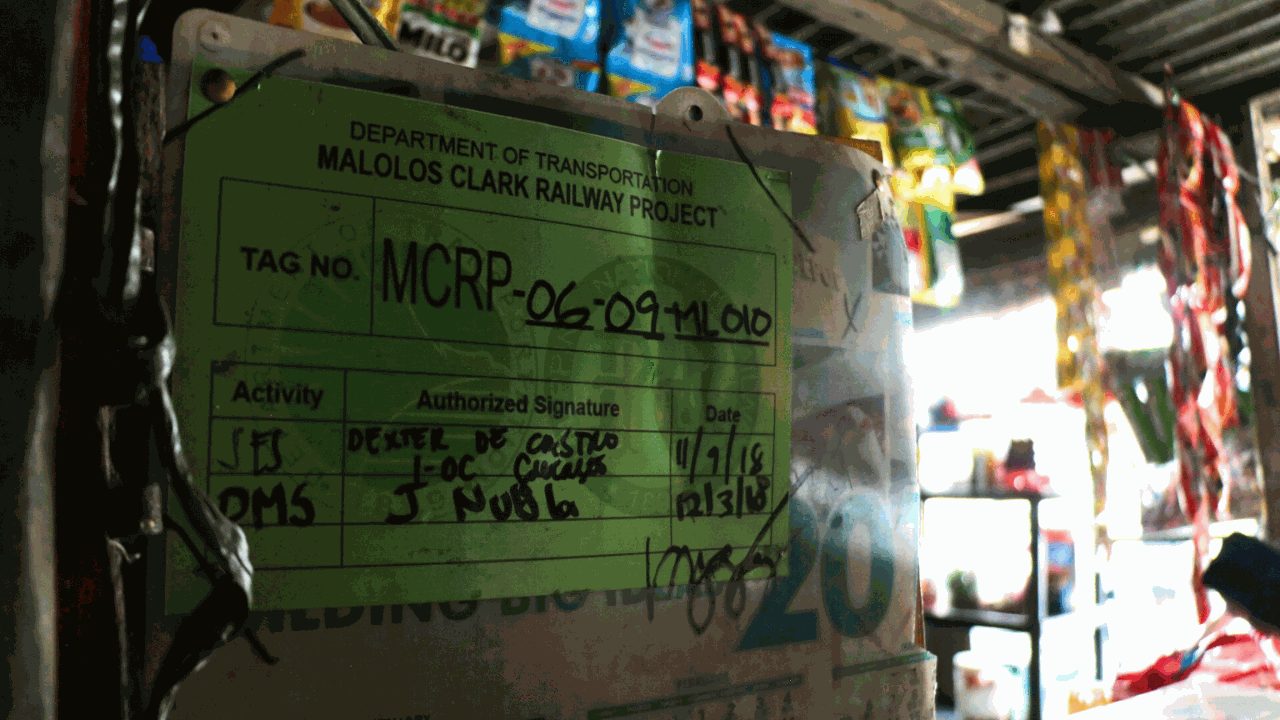

A parcellary plan is one of the key components for the MCRP alignment containing the historical structures, bodies of water, immediately available land for construction and land needed for the 30-meter ROW. It determines the areas that contractors can freely work on and structures that have yet to be cleared before any construction can start.

Inaccurate parcellary maps, however, hounded the initial feasibility studies for the MCRP that gave birth to a series of ROW and land acquisition woes for DOTr.

The DOTr has a ROW and Site Acquisition (ROWSA) team, in charge of identifying every parcel of land affected by the project and its ownership. The team determines the amount and type of compensation for project-affected persons, allowing the agency to secure a clear land title and access to the site, among others.

When the project started, the DOTr said it had only four members in the ROWSA team. As of October 2024, it has 48 employees and would need an additional 89 to meet its target head count.

To prevent these issues, Quito drew attention to how consultants for the proposed Subic-Clark Railway Project presented the initial alignment in 2022. During the presentation, her office noticed that the proposed alignment was going to pass through a residential area that was not yet reflected in satellite imaging.

“Akala nila bakante. Sabi namin, ‘[mag-]coordinate kayo sa assessor’s office, kasi ‘yung ano [alignment] niyo, marami kayong loteng matatamaan,” Quito explained.

(They thought it was vacant. We told them, ‘coordinate with the assessor’s office, because your alignment will hit several lots’.)

After liaising with the assessor’s office of Angeles City, the consultants for the Subic-Clark Railway Project changed the alignment.

“Latag kayong alignment,” said Quito. “Mas maganda kung ma-verify talaga natin ‘yung mga alignment kasi matutulungan din naman namin sila kung sakaling magka-problema,” she emphasized.

(Present to us the alignment. It’s better if we verify the alignment because we can help in case there would be issues.)

Costs weigh on benefits

To bankroll the MCRP, the Philippine government entered into a multi-tranche financing system with the ADB to access the funding.

DOTr Planning and Project Development Undersecretary Timothy John Batan said this arrangement is intended to minimize the commitment fees incurred when the loan funds are left unused. The commitment fee is calculated at 0.15% per year, charged from the undrawn loan amount.

The loan agreement for the first tranche of the MCRP worth $1.3 billion (P66.83 billion, based on July 11, 2019 exchange rate) was signed July 11, 2019 by then-Finance secretary Carlos Dominguez.

Based on the Audited Project Financial Report submitted to the ADB on June 26, 2023, the DOTr has twice requested restructuring of the loan validity of the first tranche to accommodate the project delays. The first tranche, which was supposed to expire on Dec. 21, 2021, was revised to Dec. 21, 2022, and then to June 30, 2024.

This resulted in the government paying commitment fees amounting to P74.67 million in 2022 alone for unused loans, all attributed to delays in the project.

Compared to other infrastructure financing options, Batan said borrowing from ADB, whose loan agreements include commitment fees, is “the relatively cheaper cost.”

It is important to note that commitment fees are on top of interest rates and any other financing charges. For ADB loans, the standard amortization is at 2.17%.

The ADB has disbursed P47.40 billion to the Philippine government as of December 2023, based on MCRP’s audited financial statement that year.

A cost-benefit analysis by the ADB found the project viable, with a 12.3% economic internal rate of return. Under various scenarios, including a 15% increase in costs, a 15% decrease in total benefits and a two-year project delay, ADB said “the analysis shows the project remains viable in all cases.”

But for Franco, the delays in the MCRP due to resettlement and ROW now seem to chip away at its potential benefits.

“Imbes na napapakinabangan na ng tao ‘yung tren, wala, tumatagal,” he said. (Instead of people benefiting from the train, the project gets prolonged.)

This story was produced with support of the Internews Earth Journalism Network.