When severe tropical storm Kristine (international name: Trami) unleashed its wrath in many parts of the country last week, the Philippines just finished hosting in Manila a five-day Asia-Pacific Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction (APMCDRR) from Oct. 14 to 18.

The conference, held in partnership with the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, brought together governments, civil society, the private sector and other stakeholders “to share best practices, review risk reduction efforts and make commitments to reduce disaster risk.”

The Philippines, being No. 1 among 193 countries ranked by the World Risk Index for the third consecutive year with “highest risk of disasters from extreme natural events and negative climate change impacts,” should gain much from the conference, specifically in reviewing its national and local risk reduction measures and learning from the innovative solutions of other countries.

Indeed, we Filipinos are known to be resilient, standing up and bouncing back right after every calamity. The dictionary defines resiliency as the “ability to recover from or adjust easily to misfortune or change.”

As President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. said in his speech at the APMCDRR, “Much has been said of the resilience of the Filipino spirit.”

“While nature has gifted us with natural wonders, it has reminded us of its formidable power. We are visited by more than 20 tropical cyclones in a year,” he said.

However, resilience has its limits. We can’t and shouldn’t always be content seeing the government distributing relief goods. We can’t simply move on with our lives each time disaster strikes. We should demand more from the government at the national and local levels.

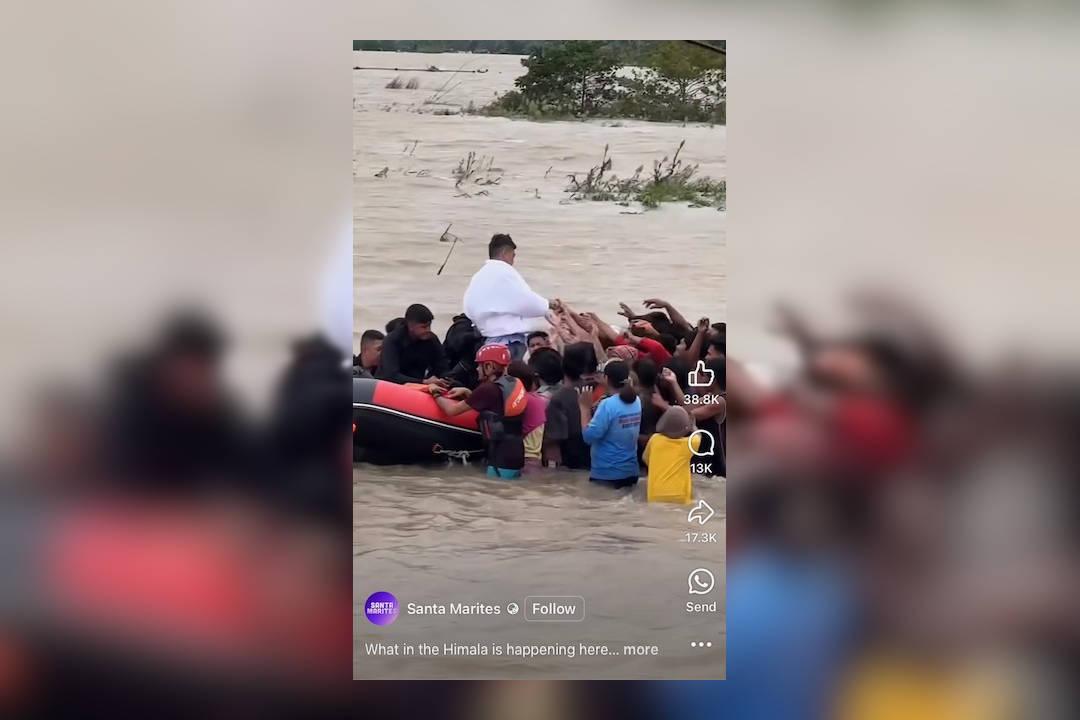

It’s painful to see residents of Camarines Sur reaching out for what looks like cash being handed out by Gov. Luigi Villafuerte, who was standing on a small boat, while his brother, fifth district Rep. Miguel Luis, was giving an old woman P500 cash while navigating the floodwaters on a boat. Witty netizens tagged the similar acts as “boat buying.”

In the aftermath of Kristine’s devastation, netizens also commented on posted photos of a damaged bridge in Camarines Sur. One had a caption: “Sobrang nipis naman … makapal pa ‘yung mukha ni Gov. Luigi d’yan.”

These incidents in Camarines Sur, one of the provinces hardest hit by Kristine, clearly illustrate how poor and corrupt the country’s system is in reducing disaster risks and providing relief to the victims.

As of 8 a.m. on Sunday, data from the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council show that 218 road sections and 40 bridges were damaged and not passable, the bulk of them in the Bicol Region and Cagayan Valley.

Kristine has so far left 79 people dead, 48 of them in Calabarzon, 28 in the Bicol Region, two in Zamboanga Peninsula and one in Central Luzon.

As of Oct. 26, the Department of Agriculture placed the storm’s damage to the agriculture sector at P1. 69 billion, while the Department of Education estimated the damage to school infrastructure at P2.67 billion, including P2.1 billion for reconstruction and P513 million for repairs.

For as long as the government continues to build or tolerate contractors building sub-standard public infrastructures, much of the money from our taxes will be going to repairs and reconstruction of disaster-damaged structures.

Sen. Joel Villanueva has questioned where the Bicol Region’s P61.42 billion allocation in the last two years for flood control under the Department of Public Works and Highways had gone, lamenting the massive flooding there that resulted in deaths and damage to property.

People still question the location of the completed 5,500 flood control projects that Marcos bragged about in his State of the Nation Address last July.

Kristine has magnified the urgent need for stronger government action to address climate justice, according to the ASEAN Parliamentarians for Human Rights (APHR). Given that at least 20 typhoons visit the Philippines every year, the group said the country “has a high climate insecurity rate” that impacts communities, vulnerable populations and livelihood.

Climate justice is deemed the “greatest human rights challenge of our time,” affecting several human rights, such as the right to life, health, food, water, housing, security and Indigenous peoples’ rights.

APHW calls on the Marcos administration to “devise and implement stronger and more sustainable climate solutions that put the safety and wellbeing of Filipinos at the center.”

My simple understanding of this is that government people, particularly those involved in public infrastructure and environmental concerns, should “moderate” their greed and spare the allocations for roads, bridges, airports, flood control and other structures from corruption so that funding won’t be short for good quality, disaster-resilient projects, and ensure that these projects won’t harm the environment, including the coastal and marine resources.

The upcoming elections present us with the opportunity to choose the people we will elect in positions of power. Not everyone who promises to “serve the people” does so once elected. Most of them tend to forget that, ending up serving their personal and business interests.

Make sure that our resiliency is not taken advantage of. We should stop being resilient to the biggest man-made disaster that has struck the country for so long, that is, politics.

The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.

This column also appeared in The Manila Times.