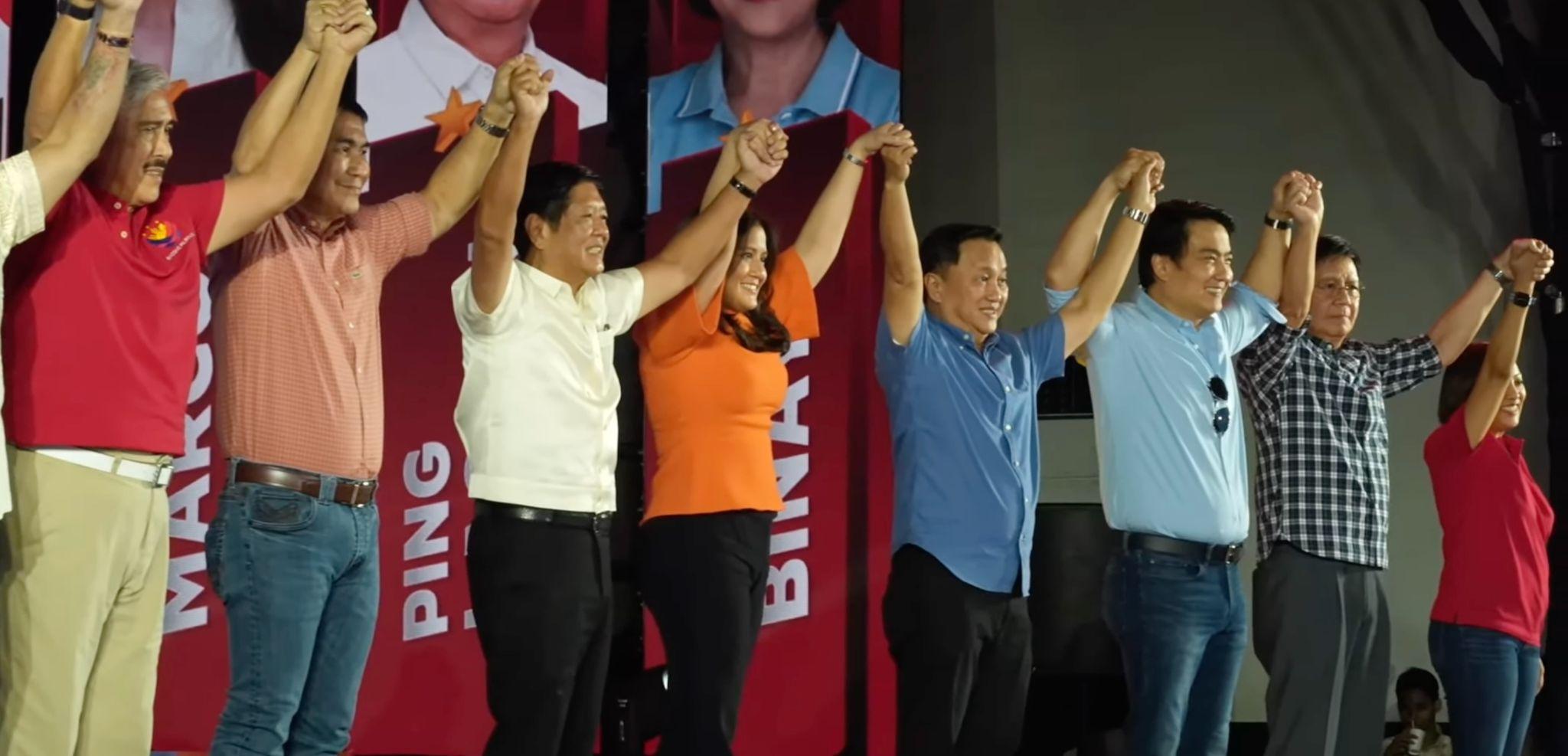

In the Oct. 1 to 8 filing of certificates of candidacy (COCs) for the May 2025 national and local elections, prominent names and familiar faces stood out among those eyeing seats in the Senate.

What’s common among senatorial aspirants Camille Villar, brothers Ben and Erwin Tulfo, Abby Binay? They all have a sibling in the so-called upper chamber.

Villar’s mother, Cynthia, and Binay’s sister, Nancy, will be ending their two-term limit, but seeking the mayoralty post in Las Pinas City and Makati City, respectively. The Villars and Binays have long been in politics, occupying both local and national positions.

Sen. Raffy Tulfo is a first-term senator. His wife Jocelyn and son Ralph are members of the House of Representatives. Jocelyn is a nominee of the ACT-CIS party-list while Ralph represents Quezon City’s second district. Ben and Erwin have been in the so-called “magic 12” of preferred candidates for the 2025 senatorial polls.

Another prominent name among the 184 senatorial aspirants is reelectionist Sen. Imee Marcos, elder sister of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. and mother of Ilocos Norte Gov. Matthew Marcos Manotoc. She is also a first cousin of House Speaker Ferdinand Martin Romualdez and an aunt to the president’s son, Ilocos Norte Rep. Sandro Marcos.

Why do we always come across such familiar surnames during elections? Why do they treat electoral positions as if these can be inherited or passed on from one to another family member?

Here are four things you need to know about political dynasties:

1. What are fat political dynasties?

“Fat” political dynasties are families that occupy different elected positions at the same time or sabay-sabay, as defined in the paper “From Fat to Obese: Political Dynasties after the 2019 Midterm Elections” by Ronald Mendoza, Leonardo Jaminola and Jurel Yap.

“Thin” dynasties, on the other hand, are families who are successively elected in the same jurisdiction, serving one at a time or sunod-sunod.

Michael Yusingco, a senior research fellow at the Ateneo Policy Center, said, “We have seen the pattern that political dynasties are growing in number.”

He added: “And also, we know or we observed that dynasties are growing fatter. Ibig sabihin, ‘yung mga miyembro (of dynasties) na nakikilahok sa eleksyon, dumadami na rin. (It means, members of dynasties who participate in the elections are also increasing.)”

The country’s two highest-elected officials, President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. and Vice President Sara Duterte, are examples of those who belong to “fat” dynasties, whose family members are exchanging positions when one reaches the constitutional term limit.

The president himself was once a vice governor, governor and representative of Ilocos Norte, and a senator. Sen. Imee Marcos had served as governor and representative of Ilocos Norte. Their mother, former first lady Imelda Romualdez Marcos, was also a member of the House from 2010 to 2019, also representing the same seat that is now occupied by the president’s son, Sandro Marcos.

The Duterte siblings currently dominate Davao City. Paolo Duterte serves as the city’s first district representative and Sebastian Duterte as its mayor. Paolo was vice mayor of Davao City, the same seat once occupied by Sara and their father, former president Rodrigo Duterte. Rodrigo was city mayor for more than 20 years while Sara was mayor for nine years.

2. How do dynastic politics impact the people?

“‘Yung mga problema ng taong bayan na nangangailangan ng policy and legal answers or solutions ay hindi natutugunan kasi ‘yung mga mambabatas…dahil nga miyembro sila ng mga ‘fat’ dynasties, ang primary goal nila is ‘yung sariling interes nila,” said Yusingco.

(The problems of the people that require policy and legal answers or solutions are not addressed because the lawmakers…as they are members of ‘fat’ dynasties, their primary goal is their own interests.)

Mendoza, Jaminola and Yap also link “fat” dynasties to poverty. Particularly in areas outside Luzon, political and economic institutions enable dynastic politicians to prevail even if their leadership fails to lead the people toward development.

Yusingco explained that one of the primary motivations of these families for expanding political influence is their economic interests. He said, “Ang talagang tinitignan nila is paano nila palalaguin ‘yung negosyo nila (What they’re looking at is how they can grow their business), using their position, using their influence in government.”

He pointed out that many political dynasties have construction businesses, highlighting the conflict of interest that arises when they are also the ones approving infrastructure projects.

3. Can there be good ‘fat’ political dynasties?

“No. There can be no good ‘fat’ political dynasties,” said Yusingco, regardless of how these dynastic politicians present themselves.

In her Oct. 4 speech after filing her COC for senator in the midterm elections, Camille Villar said, “As the only millennial candidate and a member of the Filipino youth, I strongly believe [that] I can contribute towards new politics in our country.”

Senatorial aspirant Ben Tulfo recalled his and his brothers’ history of community service when confronted with questions on the possibility of having three Tulfos in the Senate in 2025. “We lorded over helping people,” Tulfo said in his speech after filing his COC for senator on Oct. 5.

“So, ‘yung sinasabing (when they say)…new perspective, new politics, or ‘yung dynasties in service, those are just PR moves,” said Yusingco.

Tulfo, refusing to be considered part of a political dynasty, compared himself and his brothers to a family of lawyers or doctors. He said, “It’s not [a] dynasty. No, it’s not. We don’t have a district.” Because all of them are running for national posts and never held local positions, they cannot be a dynasty, Tulfo reasoned.

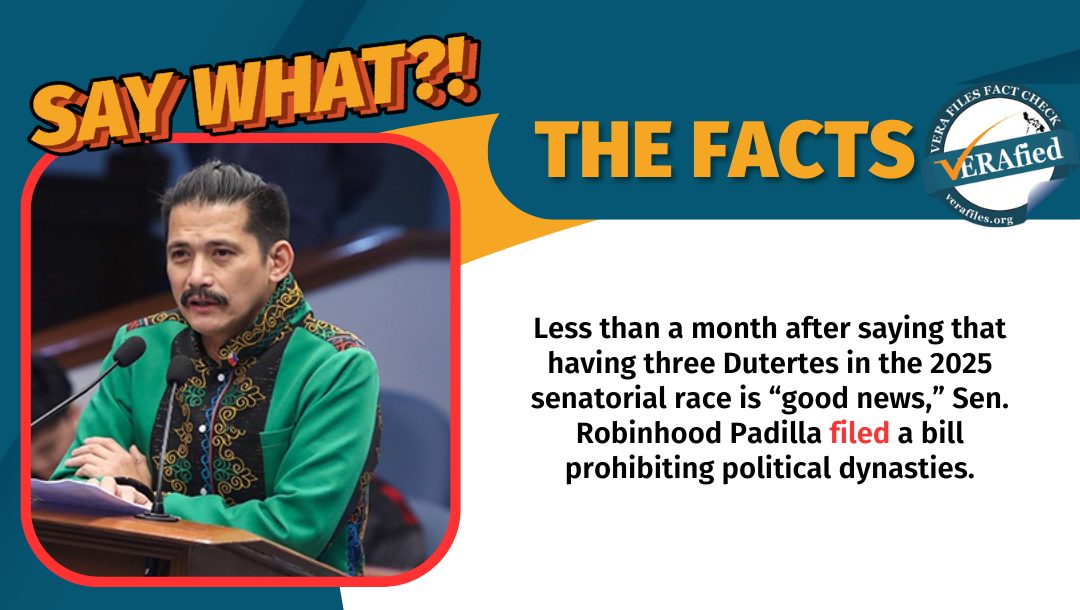

Yusingco explained that there have been efforts to manipulate the definition of a dynasty.

He said, “That tells me na kahit sila, alam nilang mali, kaya nila pinagtatakpan (that even they know it’s wrong. That’s why they are covering it up) by offering a new perspective of what a political dynasty is.” He added, “They cannot escape the fact that their family’s presence in government is detrimental to our politics and governance.”

4. Can this problem over the political dynasty be solved?

The response to the perpetuation of dynastic powers in the country must be “a basket of solutions,” said Yusingco. Among these is the enactment of an anti-dynasty law.

Article II, Section 26 of the 1987 Constitution states, “The State shall guarantee equal access to opportunities for public service, and prohibit political dynasties as may be defined by law.”

However, this provision remains to be a mere concept without a legislation to enforce it, said Senate President Francis ‘Chiz’ Escudero in an Oct. 2 press conference. He explained that the difficulty of defining a “political dynasty” is why an all-encompassing and enforceable anti-dynasty law remains elusive.

Anti-dynasty provisions have already been written in legislation, although limited to the Sangguniang Kabataan (SK) and the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM).

Section 10 of Republic Act No. 10742 or the Sangguniang Kabataan Reform Act of 2015 partly states that candidates “must not be related within the second civil degree of consanguinity or affinity to any incumbent elected national official or to any incumbent elected regional, provincial, city, municipal, or barangay official, in the locality where he or she seeks to be elected.”

Section 9(d) of the Bangsamoro Autonomy Act No. 35 or the Bangsamoro Electoral Code of 2023 partly states, “Nominees submitted by a political party shall not be related to each other within the second degree of consanguinity and affinity.”

Despite numerous attempts to introduce an anti-political dynasty law as early as 1987, Congress has failed to pass such a law. This has been blamed on the increasing dominance of legislators coming from well-entrenched political clans who expectedly would be voting against it.

Yusingco said, “Huwag tayong magsabi na we need a silver bullet or a magic pill na ‘yun na nga ‘yung anti-dynasty law para ma-solve itong problema na ito.”

(Let us not say that we need a silver bullet or a magic pill, which is the anti-dynasty law, to solve this problem.)

He stated that the “basket of solutions” also entails party-list reform towards the creation of “genuine political parties.”

Yusingco suggested an increase in the people’s political participation even after the elections “by holding the candidates or the public officials elected accountable while they are in office.”

Lastly, he said, “to make the dynastic candidates earn the post that they are running for,” the media must be more aggressive in challenging and questioning their motives and platforms.