President Duterte pays resprect to His Eminence Luis Antonio G. Cardinal Tagle, Archbishop of

Manila. Malacañang file photo.

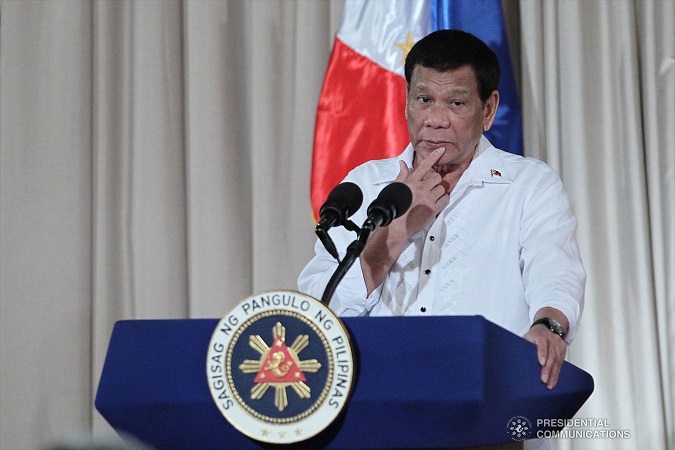

President Rodrigo Duterte’s vituperation against the Roman Catholic Church is unprecedented in recent Philippine political history. Not even the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos’s record matches it.Yet, in a predominantly Catholic country, his outrageous display of irreligiosity appears to perturb only a few.

His harangue hits at the heart of Orthodox Christianity: the doctrine of the Trinity and the crucifixion of Christ. It highlights the biggest catechetical challenge as yet to the Filipino Church, even as it finds itself in yet another crossroads.

In the broader context, the Francis Papacy has exposed seismic rifts between Church progressives and traditionalists. His “Amoris Letitia” threatens to tear the very fabric of the Church’s existence; indeed, conservative Catholic leaders see his exhortation as an immoral rewriting of marriage, and a door through which liberal ideas are smuggled into the Church.

Too, the epidemic of pedophilia in the American Church and elsewhere that has devoured thousands, and Francis’s failure to decisively address it, has served to further undermine the global Church’s integrity as a clear moral voice amidst a postmodern amoral wilderness.Worse, the Vatican itself has been wracked by revelations of high immorality that would make even libertines blush.

Here, post-EDSA 1986 politics saw Catholic bishops playing footsie with the powers-that-be (think Pajero bishops!). This, even as they actively opposed the government’s program to promote family planning in the country and prosecuted such a harmless soul as Carlos Celdran for his schoolboy antics.

All we see now is a Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines reluctant to speak a common voice of conviction, not a body of believers a prophetic Cardinal Sin once led, although the recent bombing of the Jolo Cathedral, which killed 21 Catholic faithful and wounded nearly a hundred others,has forced them to issue a pastoral letter decrying the “cycle of hate” that has gripped the country.

The pastoral letter, issued at the close of the CBCP’s 118th plenary assembly, also made an oblique reference to the President’s anti-Catholic vitriol, but said they are responding to it with “silence and prayer.” At least, for now.

To my Protestant eyes, what we have is a Filipino Church at its politically weakest.

An astute politician, the President knows this. Like Arian Vandals besieging St. Augustine’s beloved city of Hippo and its Latin Christian culture, he is exploiting the crises facing the Church to whittle away at the foundations of what is potentially the sole unified opposition to his bloody drug war, and yes, his vision of the future.

He also understands that this is no longer the time of Thomas Aquinas, who, at the height of Christendom in Europe, taught that the Church has a moral right to excommunicate and depose from power a ruler who is leading the faithful away from the gospel.

But it is beautiful to see such weakness of the Church typified by Caloocan Bishop Pablo Virgilio David, a soft-spoken French-trained bible scholar who has chosen to walk with the poor and the powerless of his diocese.

Or by Sister Maria Juanita Daño, RGS, who has lived through the horrors of Oplan Tokhang in San Andres, Bukid with her fellow parishioners. Bishop Ambo and Sister Nenet exhibit the poverty of spirit of the Sermon on the Mount.Or by the Vincentian fathers who have given refuge to the families of victims of the deadly scourge of tokhang that has decimated scores of lives in urban poor communities in Quezon City.

They also reaffirm a central message delivered by Pope Pius XII from the Vatican on Christmas Day, 1942. In his address, Pius XII said every human power has a duty to give back to the human person “the dignity given to it by God from the very beginning.” This, said Pius XII, is only possible where people once again recognized a divinely instituted juridical order, one “which stretches forth its arm, in protection or punishment, over the unforgettable rights of man and protects them against the attacks of every human power.”

These brave words said at the height of the Nazi onslaught was “a critical turning point” for the idea of universal human rights, subsequently defining postwar history and shaping governments in Europe, argues Harvard law professor Samuel Moyn’s book “Christian Human Rights”(2015).

In 1945, diplomats drafted a Universal Declaration of Human Rights that echoed Pius XII’s words, saying the Declaration intends “to reaffirm faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person.”

The Filipino Church badly needs to rediscover this legacy for such a time as ours.

Romel Regalado Bagares is a lawyer who daydreams of happily spending all his waking hours as a clueless academic. He tweets@Dooyeweerdian.