ILOILO CITY— Aura Dew Escanlar was all set to take the nursing board examinations that December of 2004 when she decided instead to put up a piggery.

What changed her mind was an offer from the Quedan and Rural Credit Guarantee Corp. (Quedancor). Called “the poor man’s financing institution,” the Department of Agriculture’s (DA) credit guarantee arm was giving out loans in the form of piglets and feeds, with a buy-back scheme that assured borrowers some income.

Escanlar then used her parents’ savings to build pigpens and buy piglets, and signed up for the Quedancor Swine Program (QSP). Less than a year later, Escanlar lost almost everything. The income from the buy-back scheme was always delayed, and the feeds came late or were not delivered at all. After 50 of her piglets died, Escanlar stormed the Quedancor regional office here. “You have turned my farm into a graveyard,” she told Quedancor employees.

Escanlar was among the angry borrowers who called up or descended on the Quedancor regional office, their names listed in logbook entries from October to December 2005, many of them financially ruined by the QSP

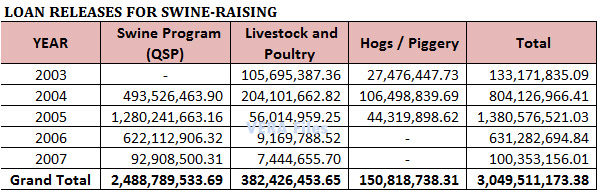

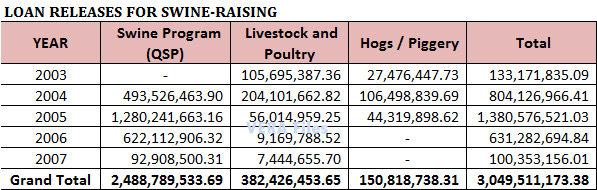

The QSP was a dismal failure, said a Quedancor official, because “we lost control of the program.” This also meant losing control over the P3 billion pesos that Quedancor poured into it from 2003 to 2007. The biggest chunk of the money went to Region 6 (Western Visayas), which got more than half of all QSP funds in the first three years of the program alone.

The QSP was a dismal failure, said a Quedancor official, because “we lost control of the program.” This also meant losing control over the P3 billion pesos that Quedancor poured into it from 2003 to 2007. The biggest chunk of the money went to Region 6 (Western Visayas), which got more than half of all QSP funds in the first three years of the program alone.

Where the money went and how it disappeared is being investigated by the Senate and the Office of the Ombudsman. But documents obtained by VERA Files as well as interviews with Quedancor officials, employees and borrowers reveal that the program was designed to fail, through a massive and complicated lending scheme that Quedancor was simply unfit to handle.

Lorenzo, Bolante tied to swine program

Documents and interviews also show that officials involved in Quedancor transactions were the same ones implicated in the P728 million fertilizer scam: then Agriculture Secretary Luis Lorenzo who chaired Quedancor, and then Agriculture Undersecretary for finance and administration Jocelyn “Joc-Joc” Bolante who was at the time also a director of the Land Bank of the Philippines from which Quedancor obtained billions of pesos in loans, a portion of which funded the QSP.

Like most Quedancor programs, the QSP was badly managed and poorly monitored. At one point, P747 million in fund releases to the QSP could not be accounted for, prompting the Commission on Audit in its 2005 report to say, “There is no audit trail in the district offices.”

It was the same thing government auditors had said about the fertilizer fund scam. Auditors tracking down the fertilizer fund said the audit trail disappeared after the congressional district offices released the money to non-accountable cooperatives, nongovernment organizations and foundations. The fertilizer funds were believed to have been used to fund President Gloria Arroyo’s election campaign in 2004.

RUINED LIVESBy DIOSA LABISTE ILOILO CITY—Noel Bejo and his wife decided to start a piggery in their hometown of Banate 48 km from here when they returned from Libya where both of them had worked as nurses. Thinking it would be their goldmine, Bejo signed up for a contract growing scheme with the Quedan and Rural Credit Guarantee Corp. (Quedancor), which provided a loan, and BIRKS Agri Livestock, the supplier of piglets, feeds and swine medicines. But in less than a year, Bejo’s business suffered. |

The QSP was first approved in July 2003 but officially implemented on March 3, 2004. It was initially meant for small, individual borrowers grouped into teams of three to 15 members called Self-Reliant Teams or SRT.

But on March 19, 2004, two months before the presidential elections, Quedancor revised the QSP guidelines to allow corporations, partnerships, cooperatives, federations, political organizations and nongovernment organizations to borrow cash, even without presenting any hard collateral. All they had to do was submit postdated checks. Loans need not pass through the Quedancor central office; even regional assistant vice presidents could approve them.

In Region 6, Quedancor released P96 million for the QSP in 2003. In 2004, the year Arroyo ran for president, releases jumped to P422 million.

The Quedancor board approved the program, supposedly anticipating a shift in public consumption from chicken to pork because of the bird flu scare. It was patterned after what they said was a successful swine program initiated in Bicol in 2002, but audit reports say Bicol was beset with problems similar to Region 6.

At that time, the Quedancor board was chaired by Lorenzo, whom Quedancor employees describe as a hands-on official who spent a lot of time at Quedancor.

Lorenzo continued being Quedancor chair even after he had left the DA and had become Presidential Adviser for Jobs Generation. He hung on to the Quedancor chairmanship even in November 2004 when he was appointed president of the Land Bank, a conflict-of-interest situation since Quedancor owes Land Bank billions of pesos.

The Land Bank is one of two financial institutions that loaned P5 billion to Quedancor just two months before the 2004 elections. The Senate and the Ombudsman are currently investigating this loan since it carried terms disadvantageous to Quedancor. Quedancor management , however, says only P211 million of this P5 billion syndicated loan officially went to the swine program.

Quedancor insiders say that among those who often attended Quedancor board meetings was Bolante, a native of Capiz in Region 6 and a confidante of the President and her husband Jose Miguel Arroyo.

Bolante was also director of the Land Bank until he left the DA in September 2004. A Senate report called him “the declared architect” of the fertilizer scam. He was arrested and jailed in the US in 2006 for allegedly violating visa rules, and faces deportation. He is expected back in Manila any time.

Quasi-banking operations

Also a member of the board is Quedancor president-on-leave Nelson Buenaflor, a longtime agriculture bureaucrat who took over the helm of Quedancor in 2001, the same year Arroyo became president. Buenaflor is reportedly very close to Lorenzo and even gave him advice when he became Presidential Adviser on Jobs Generation.

In 2001, Quedancor was still covered by Executive Order No. 138, issued by Arroyo’s predecessor Joseph Estrada. EO 138 prohibits government corporations from engaging in direct credit programs.

But Buenaflor got the Office of the Government Corporate Counsel to issue an opinion exempting Quedancor from EO 138, on the grounds that the Quedancor charter allowed lending activities. Despite engaging in what is known as “quasi-banking functions,” the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas could not control Quedancor because it was not a bank.

When Buenaflor became Quedancor’s president, he immediately expanded operations. By March 2005, Quendancor had 14 regional offices, 63 district offices and 18 extension offices nationwide.

He also initiated a variety of programs under the umbrella of the Ginintuang Masaganang Ani Countrywide Assistance for Rural Employment and Services or GMA-CARES Project. Some of Quedancor’s programs had this acronym attached to them: GMA-CARES-Fisheries, GMA-CARES-Poultry and Livestock, GMA-CARES-Income Augmentation Livelihood for Self-Reliant Farmers/Fisherfolk, GMA-CARES-Sulong, and GMA-CARES-Swine.

District offices failed to keep track of fund disbursements made for these projects. “Daily transactions were encoded in a computer without proper review by the appropriate officer. District offices have only one accountant who is assisted by one accounting clerk, most of whom are not occupying regular plantilla items. With the volume of work they have, allegedly they almost neglect(ed) the review process,” COA said.

The weakness in the Quedancor system became glaring in the Quedancor Swine Program. There was no single set of accounting rules to guide district offices, and district personnel often differed in the proper recording of receivables. The volume of work was also huge; one employee handled as many as 400 transactions, a Quedancor official said.

BIRKS favored?

So far, auditors are partly blaming the input suppliers accredited for the QSP. Although Quedancor accredited 23 companies, the sole supplier for Region 6 was BIRKS Agri-Livestock Corp.

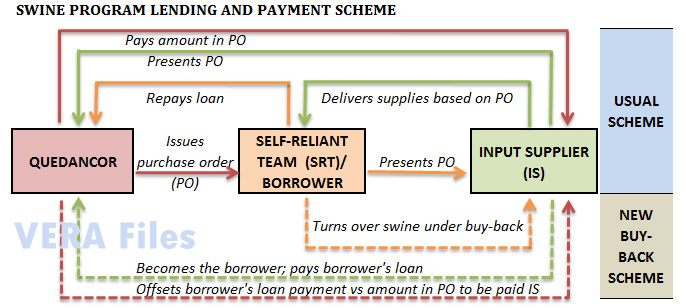

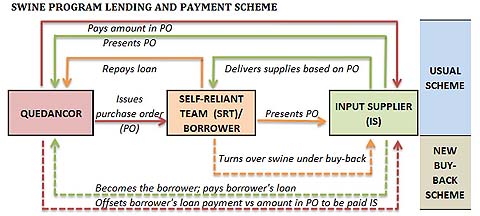

Under the scheme, the loans came in the form of purchase orders (POs) that borrowers presented to input suppliers like BIRKS. BIRKS would then give them supplies such as piglets, vaccines and feeds.

Quedancor paid BIRKS for these swine inputs. COA noted an anomaly here since Quedancor released payments in full even when supplies were delivered on a staggered basis and, in many instances, not delivered at all.

Quedancor also made payments in advance, in violation of procurement guidelines, which assume that a company doing business with the government has the financial capability to supply a project and therefore does not need advance payment to do so.

How the Quedancor was to recover the loans remains unclear. Under the contract-growing scheme, for example, input suppliers like BIRKS were supposed to buy back the swine produced by borrowers. Once the swine is pulled out by BIRKS, the borrowers’ loans would then be considered paid.

But the Quedancor district offices were unable to keep track of the pullout of swine and could not say for sure how much input suppliers were supposed to remit to Quedancor.

Besides, not all of the borrowers actually availed themselves of purchase orders. “Some borrowers identified during the actual confirmation denied having borrowed from Quedancor. It turned out that their signatures were sought by the Team Leader/Input Supplier in exchange for a sum of money ranging from P200 to P300 per signature to be able to obtain the desired amount of loan,” COA said.

BIRKS’ lawyer Hector Teodosio, whose wife April Dream was BIRKS’ former president, has turned down requests for an interview on the swine program. But he said BIRKS went bankrupt and could not even pay its rent.

According to the 2007 COA Exit Conference Report submitted in May, BIRKS owed Quedancor P205 million as of August 2006. To make the company pay, Quedancor entered into a compromise agreement allowing BIRKS to settle its debts over a period of eight years, from September 2006 to March 2015.

BIRKS, however, still could not comply with this agreement. In May 2007, it paid Quedancor P416,667 for what was supposed to be its ninth amortization.

The check, drawn against Asia United Bank’s Iloilo branch, was returned because the company did not have sufficient funds. BIRKS later paid P2.9 million in checks, again returned by the bank because BIRKS’ account had already been closed.

Procurement law ignored

It would have been so simple if only Quedancor had followed or the Government Procurement Act or Republic Act 9184, auditors said. The law requires strict accreditation of suppliers, public bidding of contracts, proper documentation and monitoring of disbursements and other measures to safeguard public money from graft and corruption.

Yet Quedancor management has insisted the QSP does not fall under the government procurement rules because no procurement transpires. It says that swine inputs never pass through Quedancor, but are exchanged between the input supplier and borrower.

Questionable suppliers like BIRKS also managed to get into the program, even if the DA’s Bureau of Animal Industry already had a list of accredited input suppliers.

BIRKS did not have the two-year track record required. It was registered at the Securities and Exchange Commission only on March 27, 2003, and applied for accreditation as QSP Input Supplier on May 7, 2003.

What auditors find disturbing, however, is that BIRKS got its accreditation papers on April 30, 2003, or a week before it even applied for accreditation. The company also had an authorized capital stock of only P1 million and a paidup capital of only P250,000, which was a sign that it was financially incapable of delivering the supplies needed by borrowers.

Quedancor officials in Region 6 said BIRKS’ accreditation started at the Quedancor central office in Manila and was endorsed to them before the program was launched.

A regional official said BIRKS lacked the capability to supply gilts (young female pigs), piglets and feeds for the QSP, and had to source these from its sister companies—Iloilo Feeds Corporation, and Nueva Swine Valley Inc. (NSVI) located at Nueva Invencion, Barotac Viejo town, Iloilo.

COA auditors in Iloilo found that NSVI, Iloilo Feeds and a third company, Nueva Foods Corp., are owned and run by the same people and share the same fund management. These companies also availed of loans from Quedancor under the latter’s Working Capital Loans (WCL) for Buyers and Processors of Agri-Fishery and Livestock program. In 2005, Nueva Foods and Iloilo Feeds owed Quedancor Region 6 a total of P117 million pesos from the WCL program.

According to COA, BIRKS’ chairman of the board is Mary Ann Ng, who also chairs NSVI and is a stockholder of Nueva Foods and Iloilo Feeds.

“Ginisa kami sa sariling mantika (we were fried in our own fat),” said a Quedancor official, commenting on the apparent misrepresentation of BIRKS.