VERA Files is 10 years old.

To mark our 10th anniversary, we are reposting 10 stories that mirror the group’s interest and commitments.

Here is the last of a three-part special report published September 2008, which won the top prize in the 20th Jaime V. Ongpin Awards for Excellence in Journalism in 2009 organized by the Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility. It shared the top honors with Roel Landingin’s three-part series on official development assistance for the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism.

One of the writers, Diosa Labiste, was awarded the Marshall McLuhan Prize by the Canadian Embassy.

MANILA, Philippines — Two months before the May 2004 elections, the Quedan and Rural Credit Guarantee Corp. (Quedancor) obtained a P5-billion syndicated loan from Equitable PCIBank and Land Bank of the Philippines but only needed at most a fifth of the money it borrowed.

It also presented “bloated figures” of its operations, including an “unachievable” repayment fee, in order to get the loan. And it had been offered better terms by the two banks but ignored or changed these. The terms were so disadvantageous that Quedancor got less than half of P5 billion.

The loan is one of the main reasons Quedancor, the credit guarantee arm of the Department of Agriculture, is now in financial distress.

An internal audit on the beleaguered state firm, interviews with its officials and employees, and documents obtained by VERA Files show that when Quedancor negotiated with the banks, it was already in the red because of its various failed lending programs.

It had also suddenly expanded operations under the Arroyo administration, creating regional, district and extension offices. Mass hiring caused the Quedancor bureaucracy to balloon from 520 in 2001 to 1,721 in 2004.

The firm was scouring for money to finance pending loan applications of up to P759 million, but there was no firm assurance of fresh funds coming from the national government, its traditional source of money.

It was at this point that the 11-member Quedancor board, chaired by then Agriculture Secretary Luis Lorenzo, approved a proposal to tap the capital market, where long-term funds such as bonds and stocks are traded.

Quedancor, however, “availed (itself) of (a) much bigger amount compared to the needed funds to finance its losing operations,” revealed the internal audit done last year.

The audit report, copies of which have been submitted to the Quedancor board, Malacañang, the Office of the Ombudsman and the Commission on Audit, said the state corporation only needed from P491 million to P946 million, and not P5 billion, to cover its shortfall.

The Quedancor board appeared to know just how much—or how little—it needed to borrow at the time. The board issued Resolution 125 on Feb. 3, 2004 limiting the corporation’s direct borrowings to P1.5 billion.

But in a strange twist one month later, the board issued another resolution—Resolution 194—this time raising the ceiling to P10 billion “at any given time” to be borrowed from the banks listed in Resolution 125 and “other banks/financial institutions willing to negotiate with Quedancor.”

Quedancor officials said the resolution enabled the state firm to not only enter into the P5-billion loan agreement, but also to borrow more from Land Bank and transact with Equitable PCIBank (now merged with Banco de Oro).

The February memo limited borrowings to P250 million from the Development Bank of the Philippines, P800 million from Land Bank, P50 million from Manilabank, P200 million from Allied Bank and P200 million from other banks.

The board’s flip-flopping led internal auditors to conclude that “Quendancor’s decision to avail (itself) of funds from the capital market was unfounded and unwarranted due to the absence of a corporate plan and a sound financial forecast.”

To convince the board to approve the P5-billion loan from the two banks, Quedancor executives led by president Nelson Buenaflor presented what the internal audit described as “very unrealistic and operational financial operations.”

Projections prepared by senior vice president Niels Patrick Riconalla assured the board that Quedancor could repay the loan and even earn income from it, according to the internal audit.

But auditors said this was because top management based its projections on a lower interest rate—9.15 percent—and did not take into account other expenses, in particular the upfront arranger’s fees, taxes, and legal and trustee fees included in the loan.

In reality, the interest rate alone reached nearly 12 percent, equivalent to the rate of the 91-day Treasury Bill or government bond plus an extra 2.75 percent, the auditors said.

Quedancor executives also reported that the corporation was recovering 95 percent of loans it had given out in its various programs, when its actual repayment performance, according to internal auditors, was less than half.

Quedancor’s management submitted the same repayment figures to Equitable PCIBank and Land Bank obviously to entice them to invest in agriculture, which is known to be a high-risk sector, the auditors said.

What puzzled internal auditors was why the Quedancor board and management settled for the P5- billion loan when they had earlier gotten better offers separately from Equitable PCIBank and Land Bank.

One key to the puzzle is ONL Consultants, a private group that acted as Quedancor’s financial adviser in negotiating for the loans. Records show that Buenaflor, Riconalla and senior vice president for finance Leticia Santos had been meeting with ONL owners, including Norberto Ong, since September 2003, months before ONL and the banks submitted their proposals in 2004.

On Jan. 23, 2004, Equitable PCIBank and ONL proposed a P2-billion loan to be given in two releases. The interest rate would be floating, equivalent to the 91-Treasury Bill rate plus a spread of 2 percent for the first release. The spread would be 2.25 percent for the second release.

The interest would be secured through a guarantee from the Trade and Investment Development Corp. of the Philippines or PhilEXIM.

On Feb. 10, 2004, Land Bank and ONL submitted the same terms also for a P2-billion loan.

But the picture drastically changed on March 1, 2004. Instead of entertaining the separate offers, Quedancor started negotiating with the Land Bank and ONL for the P5-billion syndicated loan.

Agriculture Undersecretary Jocelyn “Joc Joc” Bolante, who has been implicated in the P728 million fertilizer fund scam, was a director of Land Bank at the time. Jose Nograles, a brother of Speaker Prospero Nograles, was then the head of the bank’s trust department that packaged the loan.

Under the deal, P3 billion would come from Land Bank and P2 billion from Equitable PCIBank, with floating interest that included a spread of 2.75 percent over the base rate—the 91-day Treasury Bill rate in this case—and would be repriced every quarter.

Quedancor also wouldn’t get the entire P5 billion. The banks required Quedancor to deposit with Land Bank an initial P130 million—the interest for the quarter—or a “holdout on cash deposit” as security for the interest.

The banks likewise required Quedancor to invest in zero-coupon bonds worth P2.718 billion, or more than half the loan, to ensure that the P5 billion principal would be fully paid after seven years. This means only P2.017 billion would actually be released to Quedancor.

Zero-coupon bonds are bought at a price lower than their face value. The face value is repaid when the bonds mature.

“Some of the terms and conditions of the proposals made by LBP, EPCIB, together with their adviser, ONL Consultants, such as the interest rate, security for the interest etc. were changed and/or were not followed, which is to the disadvantage of Quendancor,” the internal audit said.

What further bewildered internal auditors was Quedancor’s decision to have the whole P2.017 billion released in one go in April 2004 instead of spreading the releases over 10 months as proposed by the banks.

Had it opted for staggered releases, Quedancor could have programmed its releases and saved on interest charges, they said.

The auditors said Quedancor has been losing an average of P237 million every year since 2004 because of these terms. This is because it pays P508 million in interest and fees every year on the P5 billion loan, but earns only P271 million from the P2.017 billion it actually got.

The board members who approved the loan were Lorenzo, Buenaflor, Agrarian Reform Secretary Roberto Pagdanganan, Cooperative Development Authority chairman Ruben Conti, Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas deputy governor Alberto Reyes, National Food Authority administrator Arthur Yap, Gov. Rodolfo del Rosario of the League of Provinces, Nellie Ilas of the Rural Bankers Association of the Philippines, Guillermo Cua for the cooperatives, Romeo Lanciola for the fisherfolk, and Jesus Simon for agricultural workers.

Until it obtained the P5-billion loan, Quedancor had borrowed heavily from the national government through agencies such the Department of Agriculture, Department of Agrarian Reform, and the Agricultural Credit Policy Council (ACPC), which is attached to the DA. The interest rates were much lower than what the banks had demanded.

A P1-billion loan fund from the DA’s Agricultural Competitiveness Enhancement Fund, for example, charges a 2-percent annual interest. Loans from the ACPC totalling P667 million bear interest rates ranging from 1.75 to 4 percent a year. The DAR extended a P150-million non-interest-bearing loan.

In 2005 Quedancor took out more loans—P1.5 billion from the United Coconut Planters Bank for its multiseries bonds and P1 billion from Land Bank for its corporate notes—under terms that the internal audit considered more advantageous than the P5 billion loan it earlier got.

Internal auditors estimated the effective or compound interest rate on the P5-billion loan at 25.52 percent and those on the multiseries bonds and corporate notes both at 10.64 percent.

Unlike the P5-billion loan, Quedancor this time need not invest in zero-coupon bonds or open a holdout on cash deposit for its interest payment. It thus received P2.474 billion out of the two new loans compared to P2.017 billion from the P5-billion loan.

Internal auditors also said that while the P5-billion loan carried a 2 percent or P100-million upfront fee, including arranger’s fee, the new loans charged only 1 percent.

Payment of huge arranger’s and trustee fees is not unique to Quedancor, however.

The National Food Authority, then under Yap, had been borrowing from the capital market since 2003, and paying upfront fees that the COA said further contributed to the already high cost of financing.

In 2004, the NFA paid P342.65 million in arranger’s and guarantee fees for P8.5 billion in loans from Equitable PCI Bank, Metro Bank and Land Bank. Like Quedancor, it also invested in zero-coupon bonds to back up the principal. ONL was also one of its financial advisers.

In 2005, ONL served as financial adviser and Land Bank the trustee and arranger for P8 billion in loans that the NFA borrowed from Equitable PCIBank, Philippine National Bank, DBP and the Philippine Veterans Bank.

On April 26, 2004, three days after receiving the P2.017 billion from Equitable PCIBank and Land Bank, Quedancor started releasing the money to its field offices. But the entire sum was not spent on programs.

Of the P1.725 billion listed as having been released when 2004 ended, close to P250 million went to no- or low-interest activities, including Quedancor’s operating expenses of P21.4 million.

“You don’t borrow to pay for your operations,” said a Quedancor executive, aghast at how the money was spent. “This happened because no plan was ever made and presented for the loan.”

Quedancor also lent P24.4 million to its Provident Fund and charged only 6 percent interest, or half the rate it is paying Equitable PCIBank and Land Bank. The sum, in turn, was released from June to November 2004 to Quedancor officials and employees in the form of emergency and other loans.

Records show that of the 163 loans released during the period, P12 million or about half the money went to 43 high-ranking Quedancor officials including Buenaflor, executive president Federico Espiritu and senior vice president Leticia Santos.

Seven vice presidents—Alberto Guevarra, Ma. Teresa Dimo, Chito Cifra, Apolinar Gonzales, Teresita Pineda, Delano Anover and Maximo Padual—one regional assistant vice president, 15 assistant vice presidents and 17 district supervisors also got loans, ranging from P50,000 to P1 million in the case of Buenaflor and Santos. By the time ordinary employees wanted to borrow from the fund, the money had been used up.

Buenaflor, Dimo and Cifra, who was the first to avail himself of a loan, are incorporators of the Provident Fund.

In January 2006, more than a hundred Quedancor employees wrote Buenaflor and the Provident Fund board to protest the lack of transparency. They questioned the basis for granting the loans and demanded publication of the Fund’s financial statement.

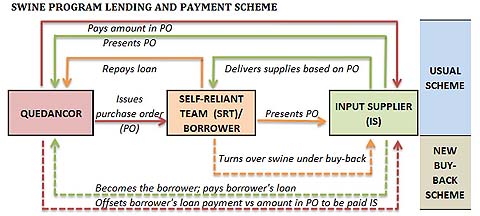

Part 1: Quedancor Swine Program another fertilizer scam

Part 2: Politicians dip hands into Quedancor funds