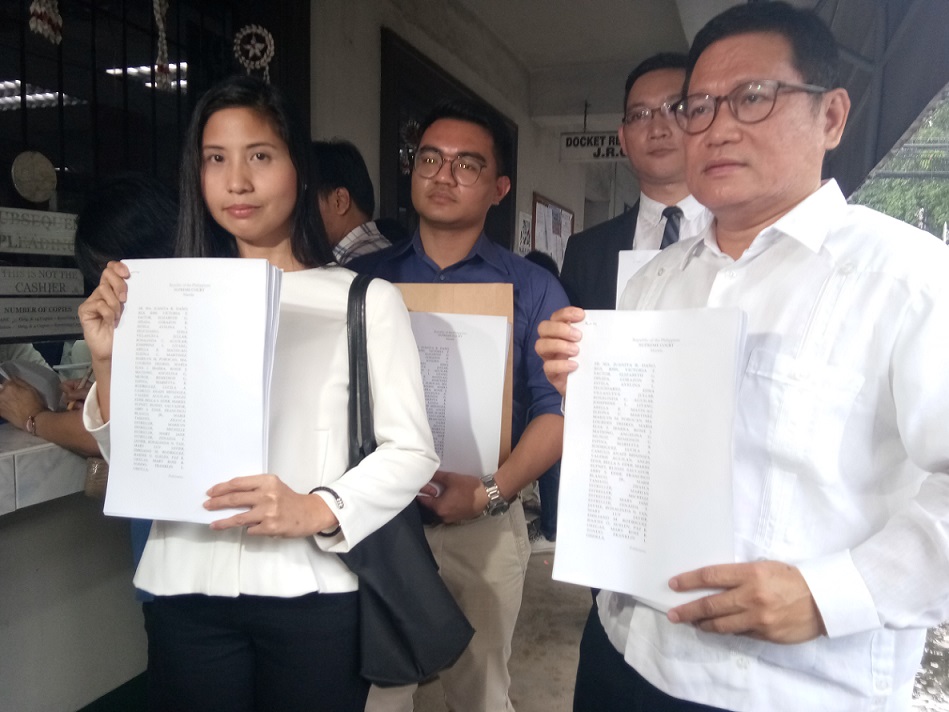

The Center for International Law files a petition for the issuance of writ of amparo for the residents of 26 barangays in San Andres Bukid, Manila. In fear for their safety, no resident from the community showed up.

When Jerry Estreller, 30, along with a friend who was just sleeping over, was killed in his home December last year, his family fled to Dagonoy market a block away for safety. Every night for two months, they would sleep atop market tables. When it rained, they would seek shelter in empty jeepneys parked on the streets.

It was, “out of sheer terror,” an act of survival. The police had also warned them not to enter the house since the Scene of the Crime Operatives would come. They never did.

Estreller, not on any drug watchlist, was allegedly killed by police, who thought he was smoking pot. In reality, he had been blowing smoke from a lit paper he only used “to drive away ants crawling near his sleeping sons.”

This tale is one of 39 harrowing narratives told by residents of San Andres Bukid, Manila in a petition filed before the Supreme Court Oct. 18 by the Center for International Law (Centerlaw).

The residents seek the writ of amparo, a remedy available to persons to ensure their safety, should their security and right to life be violated or threatened, such as in extrajudicial killings.

Aside from individual suits for protection of victims’ families in the drug war, the petition has a novel aspect — a collective suit for protection against the police in all of San Andres Bukid’s 26 barangays.

They claim officers of the Manila Police District Station 6 are liable for a “systematic violence” wrought on their neighborhood, telling stories with a recurring theme: unidentified men breaking doors of homes, shooting victims, and leaving just before police officially appear in the cordoned crime scene and clean the mess of blood and bodies.

“It’s a microcosm of what’s happening in the whole country,” said lawyer Joel Butuyan, chair of Centerlaw.

The group has recorded 35 cases of extralegal killings in San Andres Bukid that date back to July 2016, the start of the Philippine National Police’s Oplan Tokhang, up to August this year.

Some 20 nuns immersed in San Andres Bukid and visited the victims’ wakes to learn of how they died. “Because of (their) heroic deeds…this petition was formed,” lawyer Cristina Antonio said.

The petition seeks among others a temporary protection order to prohibit police to be near the families of victims. More, it asks the high court to direct the PNP to relieve MPD Station 6 police of their duty and have them transferred to stations outside Metro Manila.

It asks for a review of all police protocols, an urgent investigation on the 35 deaths and those detained without arrest warrants, as well as protection for residents who now live in fear even as they just walk along the streets they once called home.

Sought for comment, the MPD said it has yet to read the petition.

Lawyers Cristina Antonio and Joel Butuyan of Centerlaw

Duterte through an Oct. 10 memorandum directed Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA) to be the lead agency in conducting the anti-illegal drug campaign. Yet, the order states the police should maintain police visibility as a “deterrent to illegal drug activities.”

It would be “not accurate” to say the police will have no role to play anymore, Antonio said, since aside from the killings, the chilling threat, which is what they aim to remove, stays in the community as long as the officers are there.

“The drug situation has not changed,” Antonio said. “In fact, it has worsened, which just goes to show that the intervention through tokhang is not really effective.”

This is the second time Centerlaw files a petition for this writ.The first petition, granted by the Supreme Court on Jan. 31, includes Efren Morillo, who had to play dead to save his life, and the family of his four companions who were shot dead “execution-style” in Payatas, Quezon City. (See Drug war survivor claims police shot at them, ‘execution-style’).

It was the very first legal action filed by a civilian against the government’s anti-illegal drug campaign. (See Forensics, withheld evidence seen to bolster tokhang survivors)

Butuyan is hopeful the Supreme Court will grant this second petition, as it had done so before.

“We were actually emboldened to file this case because the way the court promptly acted on that petition,” Butuyan said.

The Supreme Court issued a temporary protection order five days after the Morillo case was filed. The Court of Appeals later on issued a decision giving permanent protection to the complainants.

While the latest petition filed are for residents in San Andres Bukid, Butuyan said this move, if granted by the Supreme Court, may resonate for all communities to follow suit.

“This can be a template for everyone to do in their respective communities,” Butuyan added.

Antonio believes the same. “The Supreme Court has in its hands this opportunity to call back everyone the police institution back to the rule of law,” she said.

By doing so, they may, as the petition reads, give face to the “anonymity of the victims who have been sacrificed in the current administration’s war on the poor and the powerless.”