By MIGUEL PAOLO P. REYES AND JOEL F. ARIATE JR.

IN the rules of the Armed Forces of the Philippines, AFP Regulations G 161-375 to be exact, only two conditions disqualify deceased personnel from being buried at the Libingan ng mga Bayani. The first is dishonorable discharge from the service; the second is conviction by final judgment “for an offense involving moral turpitude.”

The second may yet apply to former president Ferdinand Marcos whose burial at the Libingan, 27 years after his death, was upheld by the Supreme Court in a decision on Nov. 8, to the anger of people who say he doesn’t deserve a hero’s burial.

Seventy-six years ago on October 22, 1940, the Supreme Court itself convicted Marcos for an offense that may be judged as involving moral turpitude. He and three of his relatives were found guilty of contempt of court for filing eight separate complaints against the principal witness of the prosecution in the murder of Julio Nalundasan, even before the conclusion of the trial.

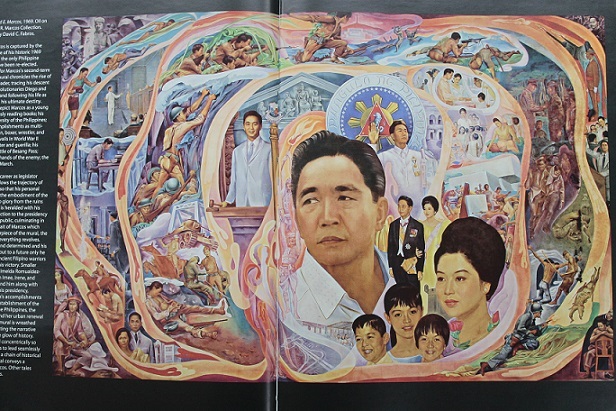

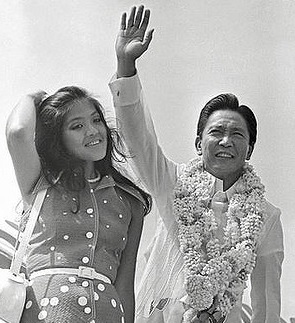

Nalundasan was the rival of Ferdinand’s father, congressman Mariano Marcos. The story goes that Nalundasan was killed by a sniper’s bullet on the night of September 20, 1935, while he was brushing his teeth by the window of his home in Batac, Ilocos Norte. This was just a few days after he defeated Mariano in the congressional elections, and was declared the duly elected representative of Ilocos Norte’s second district.

Charged with murder were Mariano, his brother Pio, their brother-in-law Quirino Lizardo, and Ferdinand, then an 18-year-old University of the Philippines student and, by various accounts, a sharpshooter.

The case went all the way to the Supreme Court, which recounts in G.R. No. L-47388, People of the Philippines v. Mariano Marcos et al., that the four filed eight separate complaints against Calixto Aguinaldo, the prosecution’s principal witness. They accused him of making false testimony against them during the preliminary investigation on Dec. 7, 1938, and during their trial.

But it turns out that they filed those eight complaints when only Lizardo’s trial had commenced. The trial of the three Marcoses had then not even begun. The rules of court require a judgment to be rendered before a charge of false testimony can be filed against a witness.

Ilocos Norte’s Court of First Instance found Quirino Lizardo, Mariano Marcos, Pio Marcos and Ferdinand Marcos guilty of contempt of court.

The Supreme Court said, “It is evident that the charges for false testimony filed by the four accused above mentioned could not be decided until the main case for murder was disposed of, since no penalty could be meted out to Calixto Aguinaldo for his alleged false testimony without first knowing the extent of the sentence to be imposed against Lizardo and the Marcoses (Revised Penal Code, art. 180).”

“The latter should therefore have waited for the termination of the principal case in the lower court before filing the charges for false testimony against Calixto Aguinaldo. Facts considered, we are of the opinion that the action of the Marcoses and Lizardo was calculated, or at least tended, directly or indirectly to obstruct the administration of justice and that, therefore, the trial court properly found them guilty of contempt,” the High Court said.

The Court of First Instance of Ilocos Norte had convicted Ferdinand Marcos and Lizardo of murder and contempt. Ferdinand, then a law student, brought the case to the Supreme Court and asked that it overturn his and Lizardo’s conviction. Mariano and Pio, meanwhile, appealed their conviction for contempt.

Justice Jose Laurel penned the decision acquitting Marcos and Lizardo of the murder charge. But it sustained the Ilocos Norte Court of First Instance’s decision that all three Marcoses and Lizardo were guilty of desacato (contempt). The Court of First Instance ordered them to pay a fine of P200 or, in case of insolvency or non-payment, the corresponding jail time. Laurel’s decision for the Supreme Court lowered the fine to P50. But the conviction stayed.

Hence, the first element in the AFP provision for disqualification is met. For the contempt of court offense, after Marcos was afforded due process by the Court of First Instance and heard on appeal by the Supreme Court, a final judgment was reached. He was guilty.

But does a guilty for contempt of court verdict necessarily mean having committed an act involving moral turpitude? What is moral turpitude in the first place?

Until 1940, the Supreme Court made only two rulings involving moral turpitude. In the first case, a lawyer was convicted of abduction with consent, and the petitioner asked that he be suspended or disbarred. The Supreme Court issued a one-year suspension to be served after he was released from prison.

In his decision on that case, In Re: Basa (December 7, 1920), in what is considered the first decision involving the issue, Justice George A. Malcolm used Bouvier’s Law Dictionary to define it.

“Moral turpitude, it has been said, includes everything which is done contrary to justice, honesty, modesty, or good morals,” Malcolm said.

“The inherent nature of the act is such that it is against good morals and the accepted rule of right conduct,” Malcolm continued.

Another pre-1940 case In Re: Isada (November 16, 1934), also penned by Malcolm, maintained that the crime of concubinage involves moral turpitude. The respondent, also a lawyer, after serving his conviction for the main crime, was suspended also for a year.

Succeeding Supreme Court rulings have either adhered to the law dictionary definition of moral turpitude as established in In Re: Basa (though they have moved on from Bouvier’s to Black’s) or have done particular refinements on how to determine if moral turpitude is concomitant with certain offenses.

The court now holds that “not every criminal act, however, involves moral turpitude” (dela Torre v. Comelec, G.R. 121592, July 5, 1996). What evolved in practice is “the way for a case-to-case approach in determining whether a crime involves moral turpitude” (Brion concurring in Teves v. Comelec, G.R. No. 180363, April 28, 2009), and “as to what crime involves moral turpitude is for the Supreme Court to determine” (A.M. 1162, A.C. 1163, A.M. 1164, August 29, 1975).

In recent cases involving moral turpitude, the Supreme Court employs three approaches in making its determination (Brion concurring in Teves v. Comelec, G.R. No. 180363, April 28, 2009).

First, to determine whether “the act itself must be inherently immoral”; second, “to look at the act committed through its elements as a crime”; and the third, “essentially takes the offender and his acts into account in light of the attendant circumstances of the crime: was he motivated by ill will indicating depravity?”

In deciding Garcia v. De Vera (A.C. No. 6052. December 11, 2003), the Supreme Court had occasion to rule on whether or not indirect contempt of court can be an offense involving moral turpitude. But following the Supreme Court’s own prescription for determining involvement of moral turpitude in a case, that decision does not automatically preclude all contempt of court cases—both direct and indirect—as free of moral turpitude.

In that case, the respondent had been previously found guilty of indirect contempt by the Supreme Court itself for having made a statement in public that in the court’s appreciation, was “clearly made to mobilize public opinion and bring pressure on the Court.”

For that very specific act alone, the Court said, “the act for which he was found guilty of indirect contempt” does not involve moral turpitude because “it cannot be said that the act of expressing one’s opinion on a public interest issue can be considered as an act of baseness, vileness or depravity.”

In the Philippines, contempt can be considered criminal or civil. According to the Supreme Court in People vs. Godoy (G.R. Nos. 115908-09, March 29, 1995), “the real character of the proceedings is to be determined by the relief sought, or the dominant purpose, and the proceedings are to be regarded as criminal when the purpose is primarily punishment, and civil when the purpose is primarily compensatory or remedial.”

In Lorenzo Shipping Corporation, et al. v. Distribution Management Association of the Philippines, et al. (G.R. No. 155849, August 31, 2011), the Supreme Court stated that “proceedings for contempt are sui generis, in nature criminal.”

The Court said that a criminal contempt “consists in conduct that is directed against the authority and dignity of a court or of a judge acting judicially, as in unlawfully assailing or discrediting the authority and dignity of the court or judge, or in doing a duly forbidden act.”

Meanwhile, it stated that a civil contempt “consists in the failure to do something ordered to be done by a court or judge in a civil case for the benefit of the opposing party therein.”

The Court continued: “Where the dominant purpose is to enforce compliance with an order of a court for the benefit of a party in whose favor the order runs, the contempt is civil; where the dominant purpose is to vindicate the dignity and authority of the court, and to protect the interests of the general public, the contempt is criminal.”

In the final decision on the Nalundasan case, Laurel said, “The inherent power to punish for contempt should be exercised on the preservative and not on the vindictive principle (Villavicencio vs. Lukban 39 Phil., 778), and on the corrective and not on the retaliatory idea of punishment.” Based only on this statement, it would appear that the contempt committed by the Marcoses was construed by the High Court as being indirect and civil in nature.

However, in the same decision, the Supreme Court described the action of the Marcoses and Lizardo as “directly or indirectly [obstructing] the administration of justice,” which could mean they committed “a duly forbidden act.”

While there is currently no jurisprudence in the Philippines that states that obstruction of justice involves moral turpitude, what Marcos and his relatives did was to harass the main witness in their murder trial with legal action. They filed eight separate complaints alleging that the principal witness for the prosecution, Calixto Aguinaldo, committed false testimony while the Nalundasan murder trial was still ongoing.

At the very least, this demonstrates a lack of faith on the judge trying the case, insinuating he is incapable of discerning the veracity of the testimony of witnesses before his court.

In American jurisprudence (see Padilla v. Gonzales, 397 F.3d 1016), obstruction of justice is considered a crime involving moral turpitude.

Since the possible sentence for Marcos and his kin for the murder of Nalundasan ranged from 12 to 20 years imprisonment to death, the Revised Penal Code provides that had they been convicted and Aguinaldo proven to have committed false testimony, then Aguinaldo would be in jail from six to 20 years. The cost of defending himself against eight lawsuits would have also been prohibitive.

Marcos and his relatives may not have committed an act that is evil in itself, but there is no doubt malice, the ill will that was inherent in their action to corrupt legal avenues for redress for their own self-serving ends.

(Miguel Paolo P. Reyes and Joel F. Ariate Jr. are researchers at the Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines Diliman. Christian Victor Masangkay provided research assistance in writing this article.)