When I was a college student sometime in the late 70s, my sister’s family invited me to watch the first-ever concert in the Philippines of hitmaker Dionne Warwick. The venue was the Folk Arts Theater, and it became packed to the rafters shortly after we arrived. A problem soon arose: The concert did not begin promptly at 8 in the evening, as the ticket said. The delay was running a full 30 minutes. As the clock continued to tick to an hour, one could sense the growing restlessness of the audience. An hour of delay was an affront to patience, to say the least.

Suddenly, attention was focused on the theater entrance. A group surrounded by a big phalanx of plainclothesmen had entered. Lo and behold, it was the Marcos family – the conjugal dictators and their three children. They proceeded to walk down the center aisle to the front row seats obviously reserved for them. Since we were seated right along the middle aisle, we had a close glimpse of them as they had walked by. Everyone began to realize why the concert was delayed.

True enough and as soon as the Marcoses were seated, Dionne Warwick glided through the stage to open with her Burt Bacharach hit “You’ll never get to heaven if you break my heart.” (“ . . . it’s really a sin to be mean and cruel, so remember if you’re untrue, angels in heavens are looking up at you.”) Was she addressing this to the guilty party that caused the show’s big delay?

I had witnessed the Marcoses’ license and exhibitionism to strut their powers before a public that they did not care about.

I remembered this vignette when a friend had sent me a blog entry of Caroline Kennedy (not the JFK daughter of the same name). The British travel writer is also a humanitarian aid worker, theater director, once the wife (now divorced) of National Artist BenCab. She was also specially linked to the Marcos children through her best friend Betsy Romualdez Francia, Imelda’s niece who owned the famous watering hole Los Indios Bravos. Among the habitués there was the writer JV Cruz.

By 1983, Cruz had been appointed by Marcos to the diplomatic service. It was in that context that he and Caroline had met in London, during which Cruz made an unusual request to Caroline. Phoning Caroline, Cruz told her of the impending visit of Imee Marcos and her partner Tommy Manotoc. (They had wed in the US in December 1982, but Manotoc’s Costa Rican divorce from Miss International 1970 Aurora Pijuan was not valid in the Philippines).

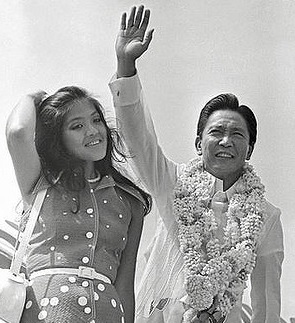

Father and daughter. Imee Marcos with the late former president, Ferdinand E. Marcos. From the article of Caroline Kennedy.

“I’ve got strict instructions from Imelda not to let Imee and Tommy out of my sight while they’re in London. They’re my responsibility. I’ve arranged a week of parties, theaters, and sightseeing. But,” he hesitated, “there’s one night I just can’t be with them. Can you take them off my hands that night for me, please?”

Writes Kennedy: “My brother in-law Elliot Kastner had a new musical, “Marilyn”, about the life of Marilyn Monroe running at the Adelphi Theatre on the Strand so I reckoned I could invite Imee and Tommy to that. I called Elliott, explained the situation and he reserved some complimentary tickets at the box office for us. He suggested I call the manager of the theatre to warn him that I would be bringing the daughter of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos. The manager was extremely courteous and offered to make all the necessary security arrangements, take us into the private VIP bar during the interval and arrange for us to meet the actors backstage at the end of the show.”

“I spoke to Imee the day before the event. I gave her the name and address of the Adelphi Theatre and told her exactly what time we should meet there. In order to avoid misunderstandings I asked her to write it all down. ‘Everything’s clear,’ she told me. ‘And please make sure you’re there ten minutes before curtain‘s up!’ I said as politely as I could. And then, more pointedly, ‘Theatre starts on time in England.’ ‘Sure, no problem!’ she replied and put the phone down.

“Five, ten, fifteen minutes – half an hour – passed and still no sign of Imee. Yet again, just as it always did in Manila, the theatre curtain was forced to wait for a member of the Marcos family. As the audience inside began to hiss and boo, the red-faced manager could wait no longer. He gave the nod for the show to begin. My heart sank. I visualized waiting in the lobby all night. I was indignant. This was discourteous not only to the management but also to the actors and the audience.”

“Finally, after what seemed like an eternity, seven stretch black limousines rolled up outside the theatre. Doors flung wide-open and uniformed men carrying armalites spilled out onto the pavement. I watched in horror as some of the armed minders rushed inside and others surrounded the perimeter, effecting a cordon sanitaire around the theatre. And, when they decided the venue was safe, they snapped their fingers, whispered into their walkie-talkies and nodded the go-ahead for Imee and Tommy to emerge.”

By this time, Kennedy’s jaws had dropped in disbelief at the show of force: “People in the street had stopped dead in their tracks. They stared incredulously, probably wondering who on earth deserved such a massive security operation. I, too, couldn’t believe my eyes. This was like finding myself in a cheap gangster movie. I couldn’t help thinking that nobody in London would even recognise Imee Marcos, let alone care who she was or what happened to her. Nobody in London was ever likely to threaten her physical harm or kidnap her.”

Kennedy continues: “By now the manager was at his wits’ end. Armed guards were illegal in London and with them posted inside and outside the theatre so flagrantly he felt he was bound to get into serious trouble with the law.”

“There was more hissing and booing from the audience as we were escorted into the theatre in the middle of Scene 2 and blindly groped our way in the dark towards our seats in the middle of the front stalls. I cringed as people making space for us to pass, were forced to stand up, dropping their bags, coats and boxes of chocolates, their seats swinging shut with loud thuds. Feeling no guilt at all, Imee then whispered to me: ‘What’s going on? What’s the story so far?’ Trying to keep my voice as low as possible I whispered back. I could feel the glares in my direction as I explained the plot. I desperately wanted to leave, preferably in the dark, so no one could see me and point the finger.”

“This was exhibitionism at its most vulgar. This was simply a very successful attempt at drawing attention to herself. And, whether it was her own idea of making a dramatic entrance or ‘Daddy’s’ orders for protecting his anointed heir, I never did find out. But seven decoy cars and nine armed bodyguards seemed, in my opinion, definitely excessive.”

In 1984, it was Irene Marcos’s turn to visit London. She was honeymooning with her husband Greggy Araneta. It was at that time that Caroline had the chance to ask Irene a nagging question about Imee that she never got to ask in that furious concert night.

“I now had a perfect opportunity to ask Irene why Imee had left her baby Ferdinand at home. ‘Daddy thought it was safer for him to stay in Manila,’ Irene replied. ‘But I think I heard her saying she was still breastfeeding?’ ‘Yes, she was.’ Irene sounded bored. But I was intrigued. ‘How on earth did she continue to do that when she was travelling around Europe?’ I persisted. Irene glanced at me as though I was stupid. ‘Simple, Caroline!’ she laughed. ‘She just expressed her milk everyday and then Daddy sent a Philippine Airlines plane to wherever she was and it would bring the milk back!’ Irene shrugged her shoulders as if to say – isn’t that what every mother does when she’s away from her newborn baby for several weeks?”

The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.