With the largest Roman Catholic population in Asia, the Philippines is the world’s third largest Catholic nation after Brazil and Mexico.

When Christina Lee first visited the country, what impressed her the most is the ubiquity of religious images, especially the Child Christ and the Virgen Mary. They are everywhere: stores, restaurants, shopping malls, airports, living rooms, home altars, and painted on jeepneys and vending carts.

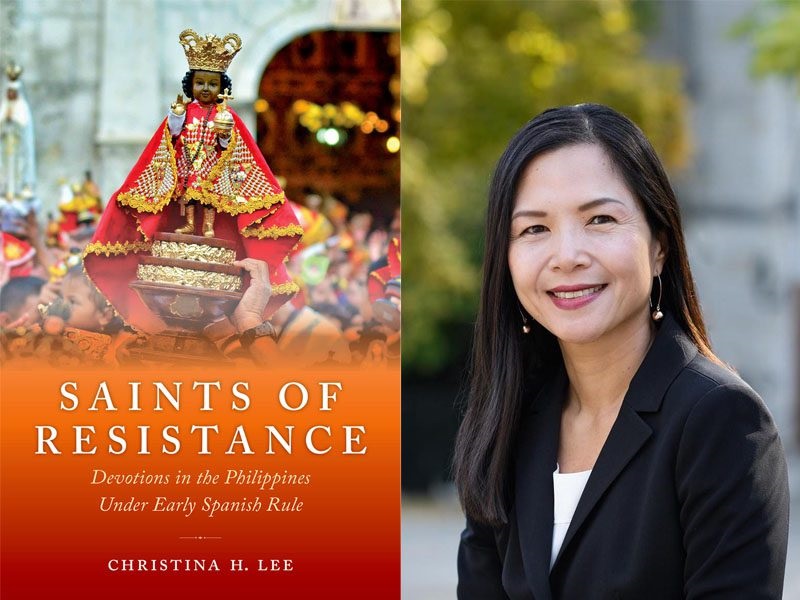

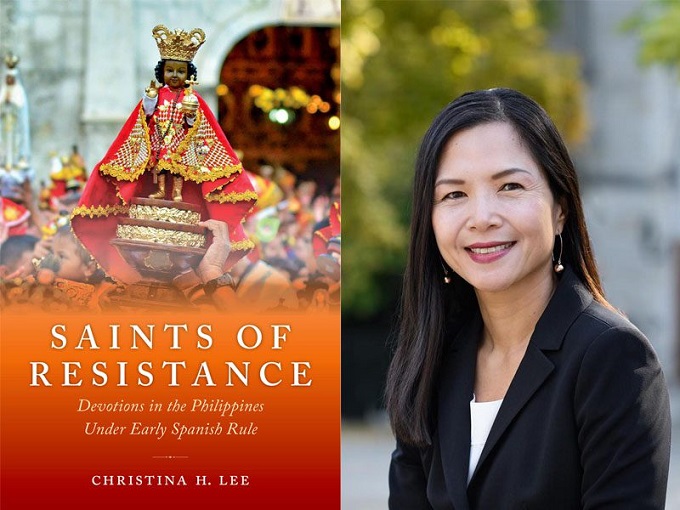

Saints of Resistance: Devotions in the Philippines under Early Spanish Rule by Christina H. Lee (2021 and 2023, 193pp.) is the only scholarly study to focus on the dynamic interaction between saints and their devotees in Spanish Philippines from the 16th to the early 18th century. It analyzes the origins and development of the beliefs and rituals surrounding the most popular saints included in the book.

Based on primary sources (first-person accounts, ecclesiastical investigations of miracles, religious literature and history, and official correspondence), Lee interrogates how Filipinos’ devotion to saints developed despite the violence and exploitation of the Spanish conquest.

Her approach is to recover the voices of the colonized natives, Chinese, and marginal Spaniards through their veneration of miraculous saints. Their devotion enabled them to relive “their grievances, anxieties, and histories of communal sufferings.”

Superstar saints: The most popular saints have “identities, origin stories, and relationship” to devotees that are unique to the Philippines, says Lee. The book covers the stories of Santo Niño de Cebu, Our Lady of Caysasay, Our Lady of the Rosary La Naval, and Our Lady of Antipolo.

Other superstar saints include the Black Nazarene of Quiapo, Our Lady of Manaog, Our Lady of Piat, Our Lady of Lourdes, Our Lady of Peñafrancia, and Our Lady of Perpetual Help, all introduced to the Philippines within the first century of Spanish conquest, 1565-1653.

Santo Niño de Cebu: The official version says it was Magellan who gave the image of the Child Jesus to Humabon’s wife in 1521; the next Spanish expedition of 1565 under Miguel Lopez de Legazpi attacked and ransacked native villages in Cebu. One Spanish soldier found the very same image that supposedly Magellan left 44 years earlier.

Lee states that there is “no definite documentary evidence” that proves Magellan brought the image of the Santo Niño to Cebu and gave it to Humabon’s wife.

As early as 1604, the Jesuit Pedro Chirino had written about the native devotion to Santo Niño; subsequent accounts by Juan de Medina (1630) and Gaspar de San Agustin (1698) noted that Cebuanos considered the Child Christ as a Diwata or Bathala and the image had been with them since time immemorial. As far as they are concerned, it was the Spaniards who took away their Diwata.

Cebuano oral tradition states that the image was an agipo or charred wood that turned into a boy. In another version, Legazpi seized the Santo Niño from the palace of the native ruler Tupas and changed its features from indigenous to Western, so that the native could not reclaim it. Both versions denounce the Spanish colonizers as appropriating the preexisting devotion, and not the other way around.

Our Lady of Antipolo: Its official history starts in 1626 when the new governor of the Philippines, Juan Niño de Tovara, was in Mexico waiting to board a galleon to Manila. He brought an image of the Virgen Mary from Acapulco who protected them from storms and a fire. Initially, it was brought to a church in Santa Cruz.

As the protector of galleons, its official name is Our Lady of Peace and Good Voyage. In 1662, the image was installed in Antipolo where it remained for the next 84 years. Its last galleon voyage was in 1746, and two years later, it was back in Antipolo.

Native devotion: By the 1690s, local devotion started to grow to Our Lady of Antipolo, Our Lady of the Tree, as she was known to the natives. She was the saint who sanctified the natural world of the Tagalogs and Aetas, and helped them in finding lost objects, healing illnesses, and protecting against corrupt authorities.

Its oral tradition emphasized that the image had disappeared repeatedly from her altar in Santa Cruz and always reappeared on top of a tipolo tree in Antipolo. A shrine was built on that spot.

Counter-narratives: Ultimately, native communities through oral tradition presented their own narratives and myths that counter official Spanish accounts of these saints. Devotion and cults toward saints strengthened amidst stories of dispossession and miracles.

The book traces how native communities refashioned the devotions to the Holy Child and Virgen Mary by integrating non-Catholic elements from pre-Hispanic, animistic, and Chinese traditions. Such belief system centers on the world of anitos and spirits who dwell in nature, the trees, rivers, mountains, and forests.

As Lee observes, “the subjected found ways of preserving the stories and the core beliefs that gave meaning to their lives.”

The author: A professor in Princeton University, Christina Lee’s research focuses on Iberian Spain and the Spanish Transpacific during the early modern period. She is the author of The Anxiety of Sameness in Early Modern Spain, 2015; co-editor of The Spanish Pacific, 1521-1815: A Reader of Primary Sources, Volume 1, 2020 and Volume 2, 2024.