Twenty-two years ago, a man from Florida was reported missing after failing to return home. It was only recently that his family learned of his whereabouts. His car was found submerged in a pond, police were told. Thanks to a former resident who was looking at his old neighborhood through Google Earth.

In similar fashion, back in 2014, the same technology became instrumental in the accidental discovery of the vast tracts of rice terraces tilled by an indigenous peoples (IP) group in the province of Antique. Emmanuel Lerona, a University of the Philippines Visayas lecturer and one of the founders of Panay Bird Club, was looking for areas where they could document rare and endemic species of birds.

Unnatural feature

While searching for dense forests through the Google Earth map, Lerona was surprised to see something different as he was looking at the mountain-area of Antique. “Instead of just light and dark areas to indicate peaks and slopes and ridges of mountain, I saw a very unnatural-looking feature that looked more like spider webs,” he recalls.

Eventually, it was verified by the IP Desk Office of the Antique Provincial Government that there are, indeed, patches of rice terraces in General Fullon. Local television was quick to pick up the story. A comparison of the presence of vast rice terraces outside the Luzon Cordilleras was highlighted, considering that these massive formations have always been attributed to the Banaue Rice Terraces.

The indigenous group which has been responsible in preserving this method has remained largely unknown to many. Through the TV program, viewers learned that they identified themselves as Iraynon Bukidnon.

For the very first time, the term was used on national broadcast media.

Anthropological backdrop

These discoveries, seemingly mundane to some, provide us with a backdrop of how we can take advantage of some technologies in looking for answers, resolving issues, rediscovering the forgotten, finding the missing, and, especially, in discovering the unknown.

Not much is known about the Iraynon Bukidnon of General Fullon in Antique. Knowledge about them are limited to the literatures submitted to the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP). Commonly, these are only supporting documents when they apply for their Certificates of Ancestral Domain Title (CADT).

In the island of Panay, two native IP groups are listed – the Panay Bukidnon and the Panay Ati. Retired University of the Philippines anthropologist Dr. Alicia P. Magos, who has done extensive research on the culture of Western Visayas, referred to the mountain peoples of Central Panay as Panay Bukidnon in her article, “The Sugidanon of Central Panay” (1996). She added that the terms Kinaray-a Bukidnon and Ligbok Bukidnon may also be used. She also briefly mentioned that those in Valderrama, Antique use the term Iraynon or Irahaynon to refer to mountain dwellers.

Official and legal documents from NCIP point to the communities of Brgy. San Agustin, Busog, and Culiat, all in Valderrama, as the recognized Iraynon Bukidnon based on the CADT issued. The IP Desk of Antique Provincial Government, on the other hand, expressed that there are more mountain communities that are Iraynon Bukidnon, subject to field verification of the NCIP.

Road to recognition

This discovery in 2014 adds to the growing body of knowledge about the IPs in the Philippines. It brings up the discussion about the limited and scarce data that we have about them. The documentation of their homeland and of their way of life, provides for an avenue to share their preserved customs and traditions, to help them confront the different challenges that threaten their culture and existence, and to reestablish their identities in a society that is seemingly slowly forgetting its roots.

October plays an important part in recognizing all of these as we observe the National Indigenous Peoples Month. The theme, “Karunungan ng Katutubong Pamayanan Paigtingin: Pundasyon ng Katutubong Edukasyon” recognizes importance of the IP communities as “collective bearers of the inter-generational wisdom and knowldeges.”

In “Speaking truth to power: Indigenous storytelling as an act of living resistance” (2013), Aman Sium and Eric Ritskes put forward that, the “Land is how we/they come to know our/themselves.” The story gleaned from local TV was only a primer. In his quest to learn more about the community that he first encountered through mediated images from Google Earth, Lerona embarked on a three-year journey to unravel the stories of the Iraynon Bukidnon in General Fullon.

Documenting heritage

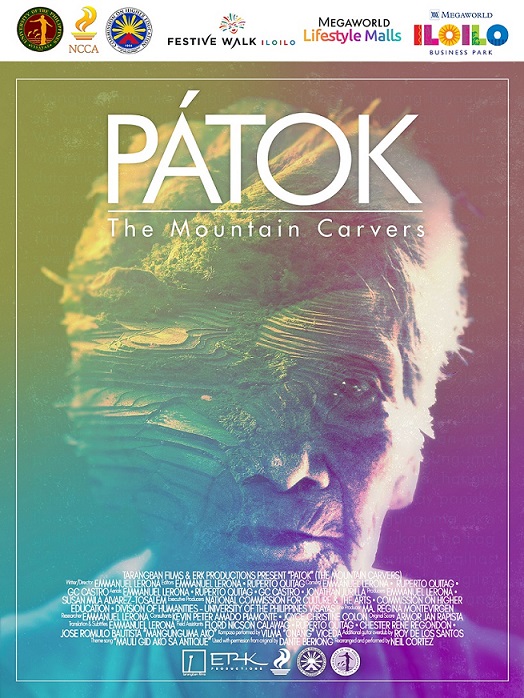

Lerona’s documentary film, entitled Pátok (The Mountain Carvers), explores the cultural traditions of the Iraynon Bukidnon that led to their construction of the monumental rice terraces. Embedded within this ingenious agricultural innovation, that they have preserved for a long time, are their intangible heritage (e.g., arts, dances, literature, agricultural knowledge). The film further examines the challenges in its preservation.

Considering the limited information that we have about Iraynon Bukidnon, the documentary serves to fill the gaps and educate the public about them. The best source of their own histories and cultures are the very people who inhabit their land. The continuation of their Indigenous existence is embodied in their stories and their traditions. These are sites and tools for survival that tell their way of life.

Perhaps we are predestined to make use of the current tools that we have, in order for us to give voice to those who have remained in their lands, who have kept their traditions, and who have preserved in their tongues the stories of the past and the stories of the present.

The Division of Humanities of the University of the Philippines Visayas had its free special screening October 19 in Festive Walk Iloilo Cinema at the Iloilo Business Park.