(The following

article is an excerpt from a case study written by the author for the

project, “Violence, Human Rights, and Democracy in the

Philippines.” The project is a joint undertaking by the Third World

Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University

of the Philippines Diliman and the Conflict Research Group,

Department of Conflict and Development Studies, Ghent University).

Philippine flag is raised in Marawi in the midst of the siege June 2017. Photo by Luis Liwanag.

The battle of Marawi in 2017, in the heart of the Islamic city in Lanao del Sur province, deviated into violent extremism that opened more fears for the future in what was an undertaking by mostly a generation of millennial fighters. The siege that lasted five months, from May to October, was unprecedented in magnitude, challenging the military in doctrine and tactics, and prompting daily sorties of air strikes that reduced Marawi to a state of destruction. It was unbelievable that two principal brothers of a family attached to the political and business elite of the Maranaos – the Muslim ethnic tribe of Lanao del Sur – had raised the stakes of Islamism beyond the call for autonomy in a fractured land.

Butig- the seedbed

It was in the

town of Butig, where events leading up to the battle in Marawi,

inspired a vision of creating an Islamic state. The sight of poverty

recedes out to the meadow in the wide green space, turning into

forest trails that lead to a well-hidden encampment – an ideal spot

to hide and train a rebel army. It was there where smaller camps

around the border and into the neighboring Maguindanao province that

the Jemaah Islamiyah trained in their cadetship of a clandestine

military school. It was in Butig where they trained with neophyte

fighters from Indonesia and Malaysia whose ties with Filipino rebels

formed – over a period of time in scattered shifts of their

ideologies – a certain kinship. They developed smaller secret cells

for trainings that broke up after the military campaign in 2000.

Those who stayed in Butig came into contact, eventually, with the

Maute brothers whose family was a mainstay in the town politics and

linked to the Moro Islamic Liberation Front as well.

When the MILF

abandoned Camp Darul Iman in Butig after successive military air

strikes in 2016, the brothers took over what was left of it and held

their trainings there. The army would attack the camp during what it

called its Haribon campaign, named after the brigade unit based in

Marawi. This campaign was alternately called the Butig campaign,

referring to its location.

The Mautes and

Abu Dar

Omarkhayam and

Abdullah belonged a family that became known popularly as the Maute

Group. The Maute brothers began their jihad in early 2014. The

brothers’ graduate degrees from abroad were the shining scepter of

their authority. There was a third man in this partnership, an

unknown rebel who goes by the alias Abu Dar, the head of the local

Khalifa Islamiya Movement. Abu Dar was involved in bombings in the

neighboring Christian cities of Iligan and Cagayan de Oro. He joined

the brothers to bring their forces together and this was how the

so-called Maute Group was formed.

In Butig, the

supposed center of the soon-to-evolve ISIS community, the Maute

brothers and Abu Dar conducted a “seminar” in October 2014, where

about 40 participants went through some heavy soul-searching,

complete with full confessions and weeping. They were supposedly to

purify themselves of their sins and vices like smoking, drinking, and

fornication. They were told that this was the way to repent. They

could atone for their sins as well as intercede in behalf of seventy

family members in their lineage. Was this the beginning of

radicalization? Was this going to be a one-way ticket to heaven?

Could they erase their sins in the name of jihad, which was going to

be the “roof to protect the community”? Sharia law was rarely

practiced by Filipino Muslims. It was only in ISIS and in Pakistan,

Brunei, and Saudi Arabia that punishment of stoning for certain

instances of fornication was done. By introducing this to a future of

the Islamic State, the Maute leaders hoped to turn the world of

Filipino Muslims – one that was generally moderate, secular, and

still adhering to folk mysticism – upside down. If the recruits

felt they knew very little of what true Islam was, in this “seminar”

they finally found their true education. The seminar was a hard blow

to their conscience and there was no letup in changing minds and

hearts until their leaders were convinced of a full conversion.

In the last phase

of the seminar, the recruits were ordered to familiarize themselves

with weapons. They were shown a Rocket Propelled Grenade, or an

R.P.G. – the kind of weapon that paralyzed military armors in the

first days of the Marawi siege. They were told that, by way of

hadith, even just carrying a weapon was going to make them blessed,

which would come with heavenly rewards. They were then made to walk

for an hour from their bare lodging to an open field that was to be

their training ground. They went through a ring of fire, they crawled

in and out of tunnels, their adrenalin fueled when live bullets

rained on them. The training was supposed to give them a sense of how

it was to be in a real firefight. At the end of the training, they

marched in a parade like an army that was born. Abdullah led them,

riding on a horse and waving a black banner with an Arabic emblem

that said “There is no god but Allah. Mohammad is the messenger of

Allah.”

By the time they

returned to Camp Darul Iman in Butig later that year (in December

2014), they had completed their all-around training. It was time to

fight, to become martyrs and absolve themselves and their families of

their sins. In that meeting, Abdullah did most of the talking while

Abu Dar quietly stood at the back. Omarkhayam was the brother, eager

for the trigger, who would draw first blood. In February 2016, in an

operation called Butig 1, he led an attack against an army detachment

in Butig’s town hall. Abdullah apparently did not know about his

brother’s plan to give the young recruits their baptism of fire.

When the army fought back, Abdullah was forced to bring in

reinforcement of about fifty men and the firefight lasted for days,

this time with bombs and artillery. Abdullah was upset at his brother

for having done such a thing. “The enemy is here,” Omarkhayam was

quoted as having told his younger brother, “Why do I need to ask

permission to launch an attack? The enemy is here, why shouldn’t we

fight?” The military believed it was Abu Dar who reinforced

Omarkhayam’s unprovoked attack on the military detachment. Butig 1

yielded political dividends for the Maute Group. A senior-ranking

fighter said the group first had a small army of thirty that grew to

about two hundred forces, and by the time the battle of Marawi

started they had about six hundred fighting against government forces

to gain control of Lanao del Sur’s capital.

A report by Gail

Tan Ilagan of the Ateneo de Davao University, “Toward Countering

Recruitment to Violent Extremism in Mindanao,” stated that in

mainland Mindanao (i.e. Maguindanao, Lanao del Sur provinces),

mosques and the madrasa schools, especially funded by money from

Saudi Arabia, were reported to be places for potential recruits

“identified through their devout worship, their regular

participation in Islamic seminars, and the kind of earnest questions

they ask during such gatherings.” While the boarding schools of the

toril essentially confine their students and hold them captive to

extremist indoctrinations, “there is little indication of the

success of mass recruitment if indeed such is being attempted in the

first place.” In Marawi the torils were known to be the parents’

last resort for delinquent children, but for some who found out that

their children were being trained in Butig under harsh conditions and

in some extreme cases, were sent to tiny, isolated islands on the

lake, they attempted to take them back. The orphans were much an easy

prey.

The grand mosque in Marawi. October 2018. Photo by Johnna Villaviray-Giolagon

Butig

2/Haribon 2 broke out three months after the first one, in May 2016.

The military was able to identify four small encampments in the Butig

hideout, and began firing artillery in their direction. There were

fighters from the Maute group that were training in Piagapo, near

west of Marawi. They came to the rescue of the fighters in Butig and

they were able to bring the battle back against the military before

the start of the Ramadan in June. The fighters were told that

striking during the Holy Month would mean having their heavenly

rewards multiplied. But the military bombardment had taken its toll.

Many were wounded and escaped to the lake using a banca to seek

medical assistance elsewhere. After Butig 2/Haribon 2, the

group continued recruiting among close relatives, school children and

orphans. Rouge fighters from the MILF and the breakaway Bangsamoro

Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF) also joined, beefing up a force, not

of ragtag, but young solid fighters.

The arrival of

Hapilon

By December 2016,

there were random air strikes leading up to what would next become

Butig 3/Haribon 3. The rebels were caught off guard, retreating to

the hinterland border of Maguindanao. There they stayed silent. Some

of the fighters had heard that one of the Abu Sayyaf leaders,

Isnilon Hapilon, was coming from Basilan island to join them. The

military had information that he landed by boat along the

northwestern coast by Illana Bay, along with fifty passengers who

supposedly included foreign fighters. This was the basis for the

third operation, believing that after such a heavy bombardment

Hapilon might have gotten killed or wounded. By all accounts, this

was big news. But Hapilon actually did not arrive in Lanao until the

second week of January 2017, according to one of the fighters, when

the Maute brothers’ group had already settled back in Butig after

the military operation. He had his own team of men, including his

son, and was given his own camp where only Abdullah and Omarkhayam

could see him.

The young

fighters in Butig were in awe of Hapilon, coming face-to-face with

the warrior who had been around since the inception of the Abu Sayyaf

in Sulu in the late 1990s. Following an inspirational speech by

Hapilon during a private and personal meeting, the fighters moved to

Piagapo, crossing the Lake Lanao and settling by the site near a

tower that was once an American settlement in the colonial days of

the early 1900s.The group stayed there for about a month, during

which there was talk of a big Marawi operation, similar to what they

had heard when Hapilon came to Butig. The other fighters, about one

hundred of them, set up camp surreptitiously and separately in the

barangays around Marawi. A big plan was afoot.

Then in April

2017, the army brigade commander in Marawi asked for more troops when

reports filtered in that there was going to be another attack. When

elite special forces moved into Piagapo, fighting ensued. Piagapo was

relatively a progressive town compared to others in Lanao del Sur

province, and the local government more or less cooperated with the

military in house searches after the Piagapo operation that took over

the rebel camp and dismantled their base.

Military mistake

It took Air Force

strikes to stop the rebels and they thought that was the end of it,

and that it would take time before the rebels could regroup and

strike somewhere else. As it turned out, the military was very

wrong. Soon after conducting the Piagapo operations, their attention

was suddenly diverted towards going after communist rebels operating

at the border into Bukidnon on the eastern flank of Lanao del Sur.

The army camp in Marawi was left vulnerable with only about a company

on guard. This explains why, despite receiving naval intelligence

reports all the way from the Western Command in Zamboanga, warning of

an impending threat by Hapilon and his comrades, the local command

was in no position to prevent the rebels’ siege of Marawi on May

23.

k9 units. Marawi Oct 2018. Photo by Johnna Villaviray Giolagon

The battle of

Marawi was officially declared over after the military killed Isnilon

Hapilon and Omarkhayam Maute in mid-October 2017. Abdullah Maute,

too, was believed killed earlier in the siege but there have been no

reports of his body being retrieved. Abu Dar escaped and tried to put

a new army together. His plan was short-lived; he was killed in a

firefight with an army platoon in mid-March 2019, in an area a mere

30 kilometers from Butig. Marawi, however, has never recovered from

the battle. It remains a devastated area and its residents still to

receive the government aid promised by President Rodrigo Duterte who,

later in his speeches, relinquished those promises to rebuild Marawi,

saying there were enough wealthy Maranao families who could provide

the needed help. He also blamed the illegal drug trade and corruption

money as impetus for the violence. By reducing the causes and

aftermath of the Marawi siege to a black-and-white issue, the

government would likely fail to address the Muslims’ future in

nation building, as previous administrations lacked foresight and

cutting-edge policies.

Marawi story

still unfolding

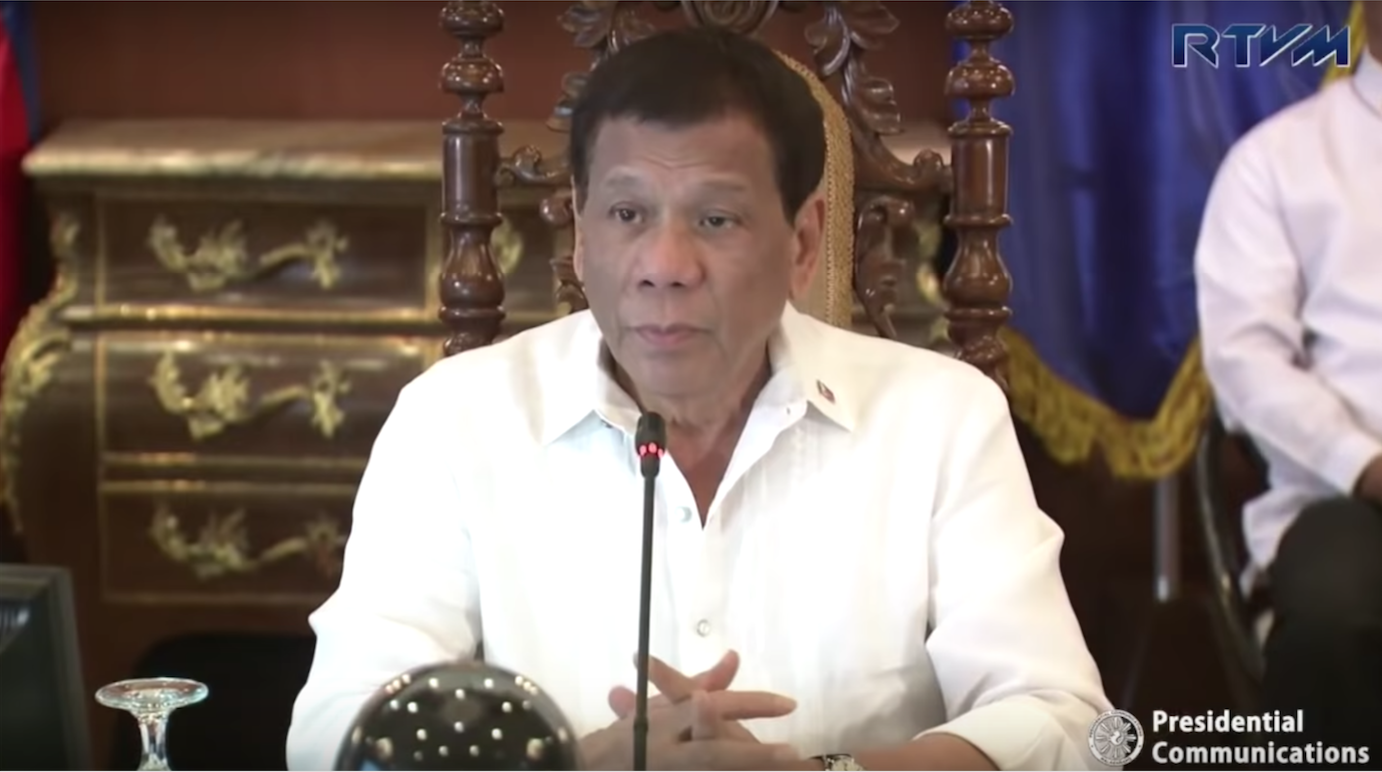

Duterte

pays tribute to soldiers who fought in Marawi Laguindingan Airport in

Cagayan de Oro City Oct. 20, 2017. Malacañang photo by Ace Morandante.

The

narrative of how the Marawi conflict came into fruition remains as

incomplete as are the many unanswered questions. For example, how

does one draw links and connect dots from place to place (rebel

strongholds) and people to people (rebel leaders) before the plot to

take over Marawi was hatched? Is it the clandestine movement of

foreign terrorists vis-à-vis the local rebel movement that spelled a

change in the trajectory of the Muslim insurgency? Mapping out the

links and alliances would be as tough and arduous as unspooling the

threads binding the clans and family loyalties, not to mention their

place as dynastic families in the sphere of local governance. But it

was certainly the call to violence over the years, the inability to

stop it at all cost, that made the southern enclaves of the Muslim

Mindanao an open field.

In

early 2019, roughly two years after the Marawi siege began, a new

Bangsamoro authority was put in place for a regional election in the

near future for a new autonomous government. It is imperative that

it forges ahead in its map to define a resurgence of Muslim pride and

demand equality among Filipinos; to reel back would no doubt bring

Mindanao into a spiral deeper in violence, serving yet again the

ingredients for another Marawi crisis in the making.