(First of two parts)

Let’s say you found out that something you’ve been eating is bad for your health, would you stop consuming it? How hard is it for someone to change eating habits and choices, for health reasons?

If you answered ‘not really’ to the first question, you’re far from alone. If you said that changing food-related habits and lifestyles is a tough assignment, you’re probably in the majority too.

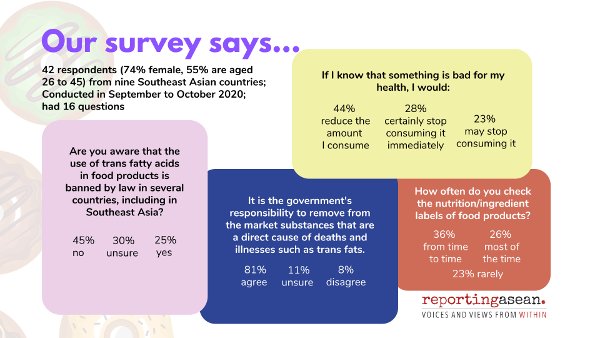

The replies to these questions, which were in a 16-point questionnaire that the Reporting ASEAN series used to find out what Southeast Asians know about harmful trans fatty acids (TFAs) in food products, point to how information about health and nutrition — and even the fear factor — are unlikely to be enough to make individuals reset their eating habits.

Asked to choose from among five responses to what they would do if they know “that something is bad” for their health, 67% of the 42 respondents chose either the reply that they would “reduce the amount” they consume (44%) or “may stop consuming it” (23%). Only 28% said they would “certainly stop consuming it immediately”, and one person said he would “not stop” consuming it.

These views appear to be consistent with the responses to this question: “How hard is it for people to change their eating habits and choices, including due to health reasons?”

The majority of respondents, or 94%, found this to be far from an easy undertaking. Of this number, 55% chose to reply that changing eating habits was “hard” and 38% said it was “very hard”, when asked to choose from five choices ranging from “very easy” , “relatively easy”, “hard”, “very hard” and “impossible”. Six percent said it would be “relatively easy” to change food habits, and no one ticked “very easy” or “impossible”.

“Not surprised (about this),” said Vannaphone Sitthirath, a Lao film producer who shifted food habits almost overnight after learning that she had high triglyceride levels as well as elevated blood pressure. “Asian people love food. We enjoy eating lots of meals with friends and family. We sit long and eat and enjoy that kind of socialising.”

But as lifestyles change, especially in cities, there are more easily available food options — but also not so healthy ones even if they are convenient or tasty, says the 41-year-old Vannaphone.

“I think we have a lot more kinds of food and drink (these days) that are not so healthy,” she said, such as frozen or packaged food. “At coffee shops, you have more and more cakes and more and more different drinks such as pearl milk, milk shakes, coffee with cream or sugar. We eat lots of pork and beef,” she added.

Just how littered with obstacles the road to better healthier food habits is something that Regidor Encabo, a Manila-based cardiologist, encounters daily in his practice.

“Discussing diet in general usually elicits negative reaction, more of sadness, disappointment, worries,” explains Encabo, whose has been seeing patients for 11 years. “When I have patients with elevated cholesterol, I emphasise what to avoid and give them free will. . . . I usually tell them, if you can do strict diet, good for them.”

Out of 10 patients who have already had ‘primary events’ such as heart attacks, angioplasty and bypass procedures, and blockage of coronary arteries – and therefore must follow a strict diet – “four to five will change their ways,” Encabo said in an interview. “Not all of them (will). What more if you’re talking of ten people who have only high cholesterol levels without an event?”

He considers himself “more realistic than idealistic” when discussing food-related issues with patients in the Philippines, where cardiovascular diseases account for 35% of deaths from non-communicable diseases. Non-communicable diseases, in turn, account for 67% of deaths in the country of 109 million people.

“It’s harder to treat someone who is depressed because he/she can’t eat food that they like because family members are too strict (in) guarding every bit of food they’re having,” Encabo remarked.

In Bangkok, shops find the ‘trans fat free’ label works well for business too. Photo J Son.

In sum, while the science is clear that substances like industrial trans fatty acids, or trans fats, leads to disease and shortens lives, taking them out from Southeast Asian consumers’ plates will involve getting past this often-tricky factor: food-related habits.

Life is outside the petri dish

After all, the use of industrially produced trans fats, which are formed in the process of adding hydrogen to vegetable oil in order to add texture and longer shelf life to processed food products, does not occur in a petri dish. Food matters interact with daily lives and habits — even was food with harmful industrial trans fats are still used in most Southeast Asian countries.

Various legal and other measures — led by the REPLACE campaign of the World Health Organisation (WHO) to eliminate the use of industrial trans fats by 2030 – are now being pushed globally and in Southeast Asia to take industrial trans fats out of plates and markets,

But this progress will take years more.

While industrial TFS are still being used in most Southeast Asian countries, consumers would be better off being knowing why trans fats — whether industrial or natural in some types of animal meat — are toxic to health and how to avoid them. At the same time, food-related habits are often default templates that people grow up in, are very set in and find very hard to break.

“Change of eating habit may indeed not be easy, but they are possible,” says Juliawati Untoro, technical lead for nutrition in the Manila-based WHO office for Western Pacific. “And more importantly, we do need to change unhealthy/bad eating habits. This change is a process, not an event and needs to be sustained. That’s perhaps one of the main reasons why it is not so easy. “

Though modest, Reporting ASEAN’s online survey, called ‘Real-life Views of Trans Fats’, provides a look into the real-life context in which public health efforts need to operate in.

Of the 42 responses to the questionnaire that was sent out in late September, slightly over half, or 55%, of the respondents were aged 26 to 45 and 74% were women. They ranged from , students, managers, employees, journalists and editors, teachers, theatre artists and creatives, from Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam.

Two years into the WHO’s REPLACE campaign, there is some ways to go for greater public awareness about trans fats in Southeast Asia, going by the survey responses.

Asked if they know that the use of industrial trans fats is banned in several countries, including in Southeast Asia, 45% of respondents said “no” and 30% said they were “unsure” about this. Combined, those two figures make up 75% of respondents who are not fully aware of this trend. Twenty-five percent, however, replied “yes”.

Do they know whether the use of industrial trans fats is banned in the country they are based in? They are “unsure” about this, 53% of respondents said.

More countries needed

The adoption of the REPLACE campaign is supposed to make it easier for consumers to avoid industrial fat, or at least encounter them less, because their governments would limit or bar their use in food products in the first place.

Thirty-two countries have some form of mandatory TFA limits in place as of May 2020, says [‘Countdown to 2023: WHO Report on Global Trans Fat Elimination 2020’]. But these cover just 32%, or 2.4 billion, of the world’s population and are usually found in higher-income countries. Twenty-six other countries have passed a TFA policy expected to come into effect in the next two years.

Cardiovascular disease is the leading killer that causes 17.9 million deaths worldwide each year, or 31% of all global deaths, according to the WHO. Dietary risks are responsible for 10 million deaths from cardiovascular disease among adults in a year, the WHO report points out. WHO data estimates that trans fats intake leads to more than 500,000 deaths each year.

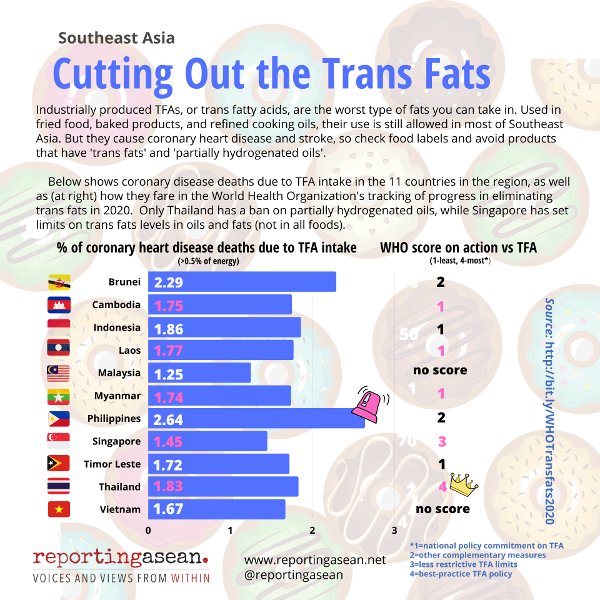

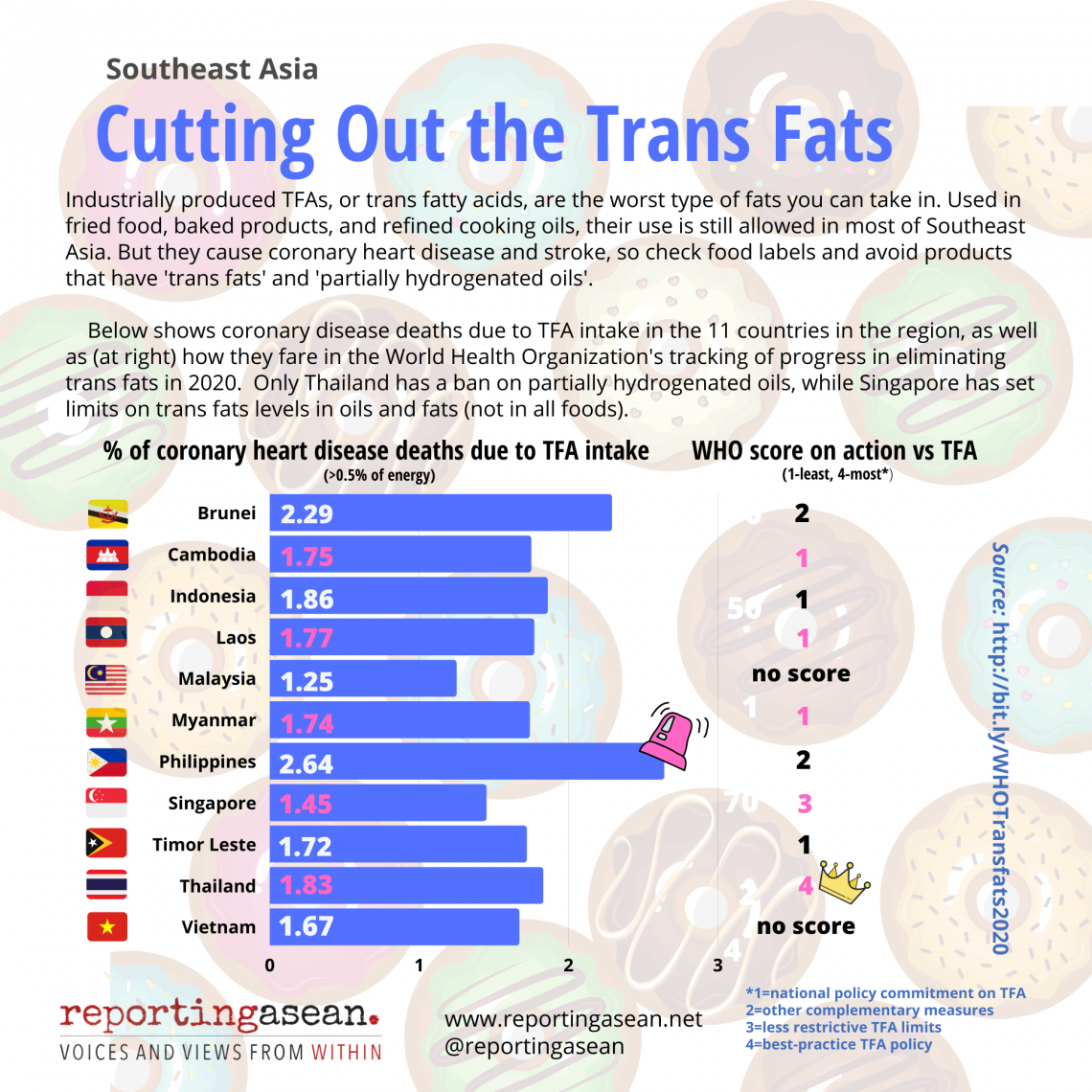

In Southeast Asia, only Thailand and Singapore have mandatory measures to bar or limit industrial trans fats.

Thailand scored the highest rating of ‘4’ in the WHO report for having a mandatory national ban on partially hydrogenated oils (PHOs), which are the main source of industrial trans fats. Thailand was the first Southeast Asian country, and the third in the world after the United States and Canada, to impose a ban on PHOs in 2019.

Singapore scored a ‘3’ in the WHO list, as it has a 2% limit on industrially produced trans fats in oils and fats (not all food products) sold in the country. The next phase involves a ban on PHOs.

Four of Southeast Asia’s 11 countries – Cambodia, Laos, Indonesia and Timor Leste – have national policies committing to eliminate TFA. They have a score of ‘1’ in the WHO report, whose ratings range from 1 to 4.

Brunei and the Philippines scored ‘2’ since they have complementary measures in place apart from national policies. Brunei has a front-of-pack labelling system that includes TFA, while the Philippines requires the declaration of TFA levels in nutrition labels. Legislation on eliminating industrial trans fats is pending in the country, which has Southeast Asia’s highest proportion of coronary heart disease deaths due to intake of all TFAs (2.64%). (The highest proportion in the world is found in Egypt at 8.29, then the United States at 7.57%.)

Not just industrial trans fats

WHO statistics define the level of TFA intake that accounts for coronary heart disease deaths as that which exceeds 0.5% of a person’s energy intake. It recommends that intake of all trans fats — whether industrial or ruminant (in certain types of animal meat) — be limited to “less than 1% of total energy intake”. For a 2,000-calorie diet of an average adult of healthy body weight, this translates to less than 2.2 grammes.

Eliminating industrial trans fats by itself would not address all aspects of trans fats’ risk to coronary and cardiovascular health, because there is a second category of trans fats that are naturally found in ruminant animals like cattle, sheep, goat and carry similar health risks.

“The effect on blood lipids resulting from changes in ruminant or industrially produced trans fat appear to be similar,” the WHO said in a [Q and A section on trans fats ].

However, in contrast to trans fat from ruminant sources, the trans fats content in PHOs are on average 25 to 45%, WHO data say. It adds that heating and frying does increase trans fat concentrations by about 3%, but is still a lot lower than levels in PHOs.

“Removing trans fats from the food supply is possibly one of the most straightforward public health interventions for reducing CVD risk and improving nutritional quality of diets,” Untoro pointed out.

Johanna Son is editor/founder of the Reporting ASEAN series. This story is part of the ‘(Un)Covering Trans Fats’ programme of Probe Media Foundation Inc.