Service bus for health frontliners. VERA Files photo by Luis Liwanag

MANILA — Leila, a logistics nurse in a government hospital, went to pick up donations from a private company after her duty. When she arrived there, she saw the boxes stacked neatly at the lobby ready for pick up.

As soon as they saw her, the staff started moving away from her, instead of helping her carry the boxes outside, even after she asked for assistance. Only the ambulance driver gave her a hand. After all the boxed were loaded, Leila removed her face mask and turned to the staff, smiled and waved to say thank you. “I waved at them again as I boarded the ambulance, but deep inside, I was hurting,” she said.

Annalyn, also a nurse, lives in a friendly community and is used to people greeting her. One day, she noticed that her neighbors, who knew she was a nurse attending to COVID-19 patients, were keeping a distance. “They’re observing social distancing. This is good,” she said to herself.

Later she realized that they actually moved away every time they saw her. “I was wrong. It wasn’t social distancing. They stayed as far away from me as possible. I don’t feel good about it.”

Dr. Reyes, a long- time infectious disease specialist, is part of a COVID-19 response team. In February, before a Luzon-wide quarantine was imposed, he and his fellow doctors decided to rent an apartment near the hospital.

But the landlady they approached, after finding out they were all doctors, refused them a place to stay. “We had to stay in the hospital because no apartment or condominium wanted us,” he said.

There are more repulsive, violent and life-threatening attacks on health workers and other front-liners over the past several days: an ambulance driver was shot and a hospital utility worker splattered with bleach because of the public’s fear of infection stemming from ignorance.

But the front-liners are not the only ones struggling to survive the discrimination and harassment as a result of the health scare during this pandemic.

Persons diagnosed as positive for COVID-19 experience worse stigma. Even with efforts to protect their identities, they are ostracized once their medical conditions are revealed.

COVID-19 patients are ostracized

“I’ve never shown my face to neighbors ever since I came home. I never attempt to wave from the window,” said Jonathan, an office worker who was discharged from the hospital after he recovered from the illness. “They will only berate me for not telling them earlier that I tested positive.”

Marko, whose father is being treated in a hospital for the respiratory illness, said some neighbors call him down for not informing them about his father’s condition. “They said if they get sick too, it’s my father’s, and our family’s fault,” he said. “They used to be nice neighbors; now they dread us.” His family was forced to close its convenience store because people don’t want to buy from them anymore.

The public’s dread towards people who contracted the coronavirus is similar to the stigma and discrimination associated with the early cases of HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) and AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome) more than three decades ago, doctors say.

Dr. Jose Narciso Melchor Sescon, Medical Specialist IV and team leader for quality assurance of Sta. Ana Hospital, a hospital dedicated for COVID-19 patients in the city of Manila, sees parallels between the current COVID-19 setting and the scenario during the early years of HIV in the Philippines, which recorded its first HIV case in 1984.

The stigma attached to COVID-19 occurred as soon as the first patient was wheeled into the emergency room, he said. While the coronavirus presented itself immediately as a pathogen that exempts no one, HIV was associated initially with gay men before it was revealed that it can infect any individual, he added.

“The similarity is in the fear of the unknown — here’s a new virus that can kill. It’s a new disease and an evolving one and just like HIV, we have to learn fast as we move along,” Dr Secon said.

“Both HIV and COVID-19 can be prevented,” he said, while emphasizing the differing infective abilities of the viruses.

HIV is transmitted through sex, blood transfusion, injecting drug use and from an infected pregnant mother to her child, while COVID-19, whose characteristics are still being studied, he said, can be transmitted through micro-droplets from the nose and mouth of an infected person to another.

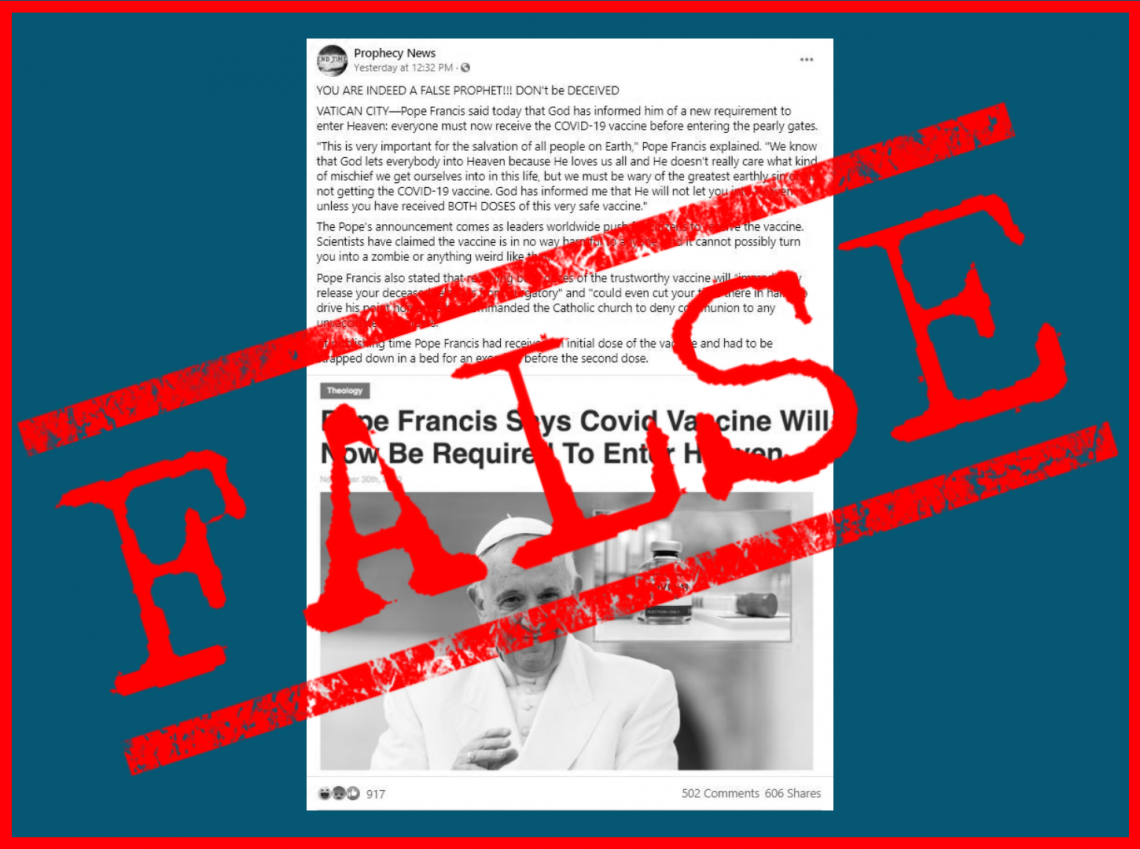

“There was no social media when HIV started its first outbreaks, but information about COVID-19 is everywhere on the internet,” said Dr. Sescon. “People, however, need to go to the accurate sources of information,” he said, citing the Department of Health (DOH), the World Health Organization and relevant published scientific journals.

Accurate information, right messaging necessary

“Wrong and unverified information are the ones that fuel discrimination,” he said. “It is now more complicated and challenging to filter, distill information in order to craft messages to improve the health response.”

Public health consultant Dr. Troy Gepte shares Dr. Sescon’s views. “I think both Covid-19 and HIV emerged as outbreaks and epidemics that have dramatically captured the public’s attention.”

“In the early 80s, people unfortunately attributed the spread (of HIV) solely among the gay community,” he explained, “when it was actually primarily through blood-borne transmission by unprotected sex, transfusion with contaminated blood and vertical transmission of an infected mother to her born child during pregnancy, labor, delivery and even during breastfeeding.”

“I think we might be experiencing the same thing with COVID-19 as we are dealing with a new virus of which the nature of its actual transmission is still being firmly established. Early advisories have focused on having precautions against respiratory droplet infection with and spread of the virus. But the observations of spread from asymptomatic infected individuals is something we have not really encountered in a massive scale like this,” Dr Gepte pointed out.

“The dread of getting infected gives way to a stigma especially against patients and health care workers,” he added.

This same fear played out in different ways when HIV cases were first reported in the Philippines in the mid-80s. Persons were shunned by their families and friends when they tested HIV-positive. Many were harassed and assaulted. Some had their houses stoned or burned down by neighbors, DOH records showed.

As a positive test was tantamount to a death sentence, suicides were high among persons living with HIV (PLHIV), who chose to end their life rather than face the stigma, the agency said. Many PLHIVs lost their jobs or were expelled from school.

All of these still happen today even with an amended HIV Law, improved policies in place and a network of treatment facilities and services that include counseling.

A former president of the professional civil society organization AIDS Society of the Philippines, Dr. Sescon says that like in the case of HIV-AIDS information campaign, there should be clear, positive, inclusive and compassionate messages relayed across audiences.

He appealed to Filipinos to rethink their attitude towards COVID patients and survivors. “We all said before in HIV — PLHIVs are not the problem, they are part of the solution. Now, I say COVID survivors are part of the solutions. Let’s do our share,” he said.

Dr. Sescon first encountered HIV 25 years ago as a resident-in-training at a hospital prior to becoming a volunteer AIDS hotline counsellor, where he worked alongside the first PLHIVs who used assumed names while doing testimonials for the health department to calm down an increasingly hostile public that dreaded a new life-threatening disease.

A 2019 HIV stigma index study by the UP Population Institute-Demographic Research and Development Foundation (UPPI-DRDF) found that fear, shame and experiencing discrimination as the reasons why PLHIVs hide their status, which can worsen their condition that in the long-term, can further the spread of the virus to the population.

The study said “stigma is prevalent; it is the silent killer that fuels the spread of HIV.

Dr. Sescon said the lessons learned from the government’s HIV response are visible in the current health crisis. It took 14 years before an AIDS law was crafted in 1998, and amended in 2018. Now, government actions are swift — it took just over a month from the first local COVID-19 transmission was reported on January 30 till the time a national health emergency was declared on March 8.

Will the stigma go away just as swift? Dr. Sescon says it would be faster with COVID 19, as it hits everyone so fast whereas HIV takes a long journey and the virus continues to be weighed down by prejudice.

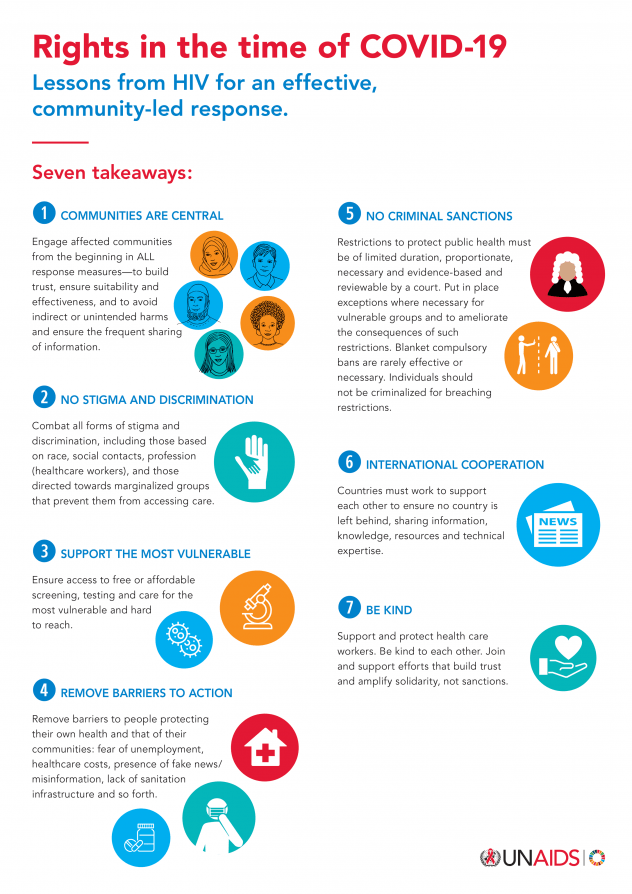

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) urges people to act with kindness, not stigma and discrimination, towards people affected by COVID-19, adding that the experiences learned from the HIV epidemic can be applied to the fight against COVID-19.

“As in the AIDS response, governments should work with communities to find local solutions. Key populations must not bear the brunt of increased stigma and discrimination as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Shortly after attacks against health workers, other front-liners as well as people with the disease were reported, the Manila city government passed Anti COVID-19 Discrimination Ordinance 2020 that prohibits acts that cause stigma, disgrace, shame, humiliation, harassment or discriminate against COVID-19 patients, persons under investigation and persons under monitoring, and will penalize violators.

Other local government units later issued similar ordinances to protect front-liners and people infected with the disease from discrimination.

The Philippines was the first country in the world to report a death from COVID-19 outside of China, where the virus first emerged in December 2019. As of April 11, 2020, the DOH has recorded 4,428 cases and 247 deaths.