By JAKE SORIANO

“THE past is never dead. It’s not even past,” wrote the great William Faulkner, a Nobel laureate for literature.

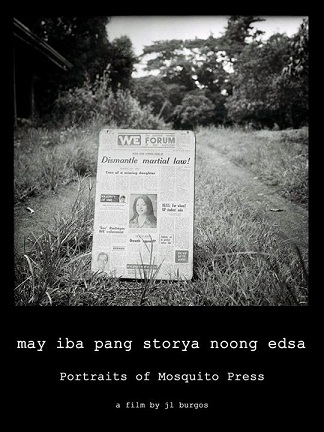

The past is clearly never dead in the new documentary Portraits of Mosquito Press by JL Burgos about the assault on press freedom and human rights during the rule of Ferdinand Marcos, especially during the Martial Law years.

The film revisits a dark chapter in the history of Philippine media. Watching it is a sentimental journey for those who have gone through that period. It is essential viewing for those who are now enjoying of the press to fully appreciate what have been invested, what have been sacrificed for the freedom they now enjoy.

The “portraits” in the film title is literal. Burgos brings together family members, as well as journalists, to pose for the camera for their photos to be taken.

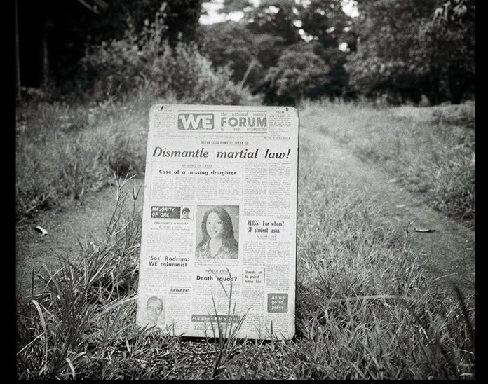

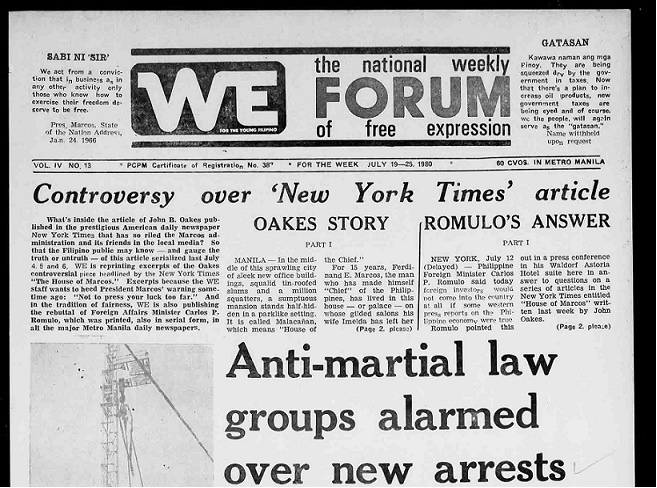

Along the way, they share stories about We Forum and Ang Pahayagang Malaya, alternative media outfits which became known as part of the mosquito press, both published by Jose Burgos Jr., the filmmaker’s father.

We Forum was an English newspaper and Ang Pahayagang Malaya was a Tagalog publication.

It was We Forum that carried reports critical about the Marcos regime at the time when the safest thing to do then was to toe Malacañang’s line.

The description “Mosquito press” came from what Marcos said in a pejorative manner to refer to an insect whose sting is annoying but not deadly and can easily be swatted.

But We Forum’s bites stung deeply when it touched Marcos’ fake medals. In the film, Joe Burgos’ wife, Editha recounted: “Marcos was holding on to a newspaper and said I will make the publisher eat this. He was holding a copy of our newspaper.”

But We Forum’s bites stung deeply when it touched Marcos’ fake medals. In the film, Joe Burgos’ wife, Editha recounted: “Marcos was holding on to a newspaper and said I will make the publisher eat this. He was holding a copy of our newspaper.”

Nostalgia and dread populate the personal recollections of journalists Chuchay Fernandez, Desiree Carlos and Joel Saracho among others, as well as of human rights lawyer Rene Saguisag and other members of the Burgos family.

Together, their anecdotes form an outstanding oral history of the period.

But the strength of the film is more than just its subject matter. In one masterful directorial stroke, Burgos films his mother’s recounting the day authorities came to arrest her husband.

She shifts from the vernacular of her earlier stories to a chilling studied English when she tells of the event. Her seeming detachment as well as the interspersing of archival photos with her narration gives the film one of its most potent moments.

Burgos said it took him some three years to finish the documentary, and the hard work shows particularly well in the historical documents he uses, from microfilms of newspaper articles to video footages, most notably that of the Ninoy Aquino assassination.

Throughout the film, Burgos films his camera taking portraits. In this reflexivity he punctuates the relevance of the past being “never dead.”

His camera, it seems, is re-recording the stories which have been recorded earlier by the journalists he is talking with, re-recording them for another generation who might not have heard these stories before but should.

In April 2007, Jonas Burgos, JL’s brother, was allegedly forcibly abducted in a mall in Quezon City and to this day has not been found.

As the film leaps forward to this event, Portraits reminds its viewers that attacks on free press, free expression and human rights in general are not from a bygone era but are still very much present in the country today.

Human Rights Watch (HRW) just earlier this year scored the Aquino administration for its poor human rights record, which include the persistence of killing of journalists, torture and enforced disappearances.

“While human rights was a key agenda for Aquino when he took office in 2010, he has failed to make good on many of his commitments, chiefly his expressed intent to end killings of activists and journalists and bring those responsible to justice,” HRW said.

The past, clearly, is not even past.