For centuries, Filipinos have treasured stoneware jars for utilitarian and ritual purposes. Known as martaban, gusi, or tapayan, these jars were produced mostly in China and some Southeast Asian countries (e.g., Thailand, Burma, Cambodia) and reached the Philippines, as part of an intricate network of global trade that existed long before Spain’s arrival in the country.

Early this June, the Elizabeth Y. Gokongwei Ethnographic Stoneware Resources Center (EYG Resource Center) has been inaugurated at the National Museum of the Philippines, in partnership with the Gokongwei Brothers Foundation, Inc. It is located at the 5F, East Wing, National Museum of Anthropology in Manila. (see: http://pamana.ph/ncr/manila/stoneware.360).

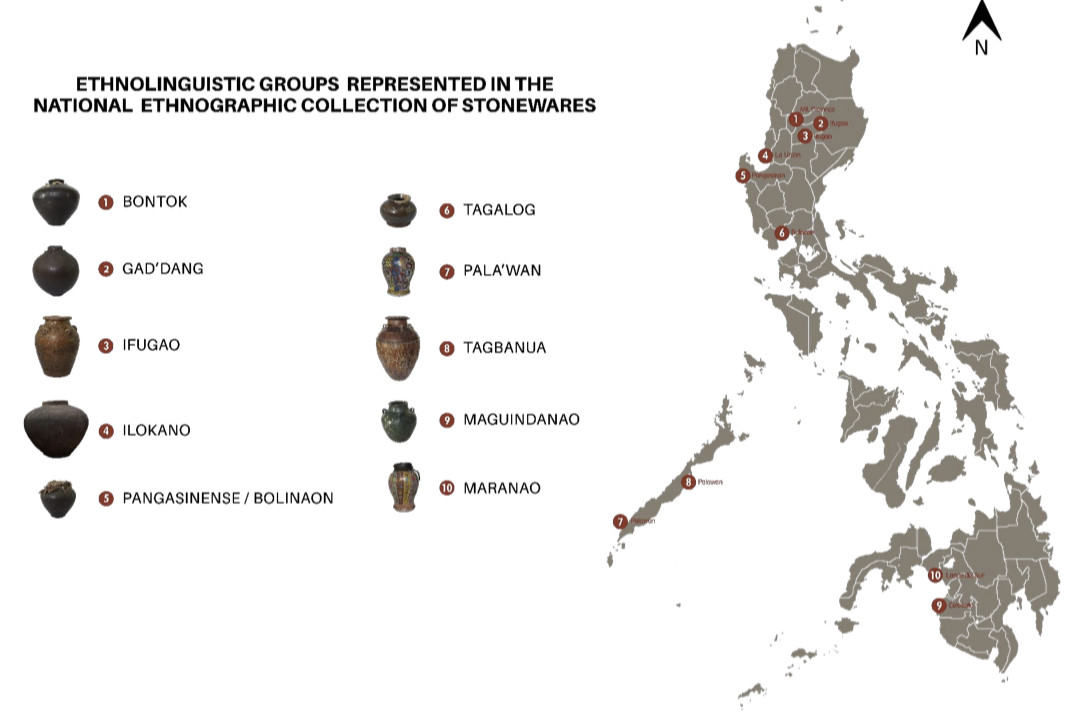

The EYG Resource Center houses over 1,000 stoneware jars, plates, and bowls (15th century-20th century) from the National Ethnographic Collection representing ethnolinguistic groups that include Bontok, Ifugao, Ibaloy, Ilokano, Gaddang, and Pangasinense communities in Northern Luzon; Tagalog, Pala’wan, and Tagbanua communities in central and southern Luzon; as well as Maguindanao, Maranao and Tausug communities in southwestern Mindanao. Some 73 Ilokano stoneware pieces are also shown, from the Ilocos Historical and Cultural Foundation Collection.

The resource center will serve as an open research facility in documenting ceramic traditions in the country and hopes to provide a better understanding of Filipino culture and identity.

Tales of survival

The jars have survived intact in three ways: in gravesites, in sunken ships, and as heirlooms.

Jars were essential containers for water, food, and beverage, especially on any sea voyage. In many shipwrecks, thousands of jars had been found as containers for water and food, tea and opium, or to transport smaller objects, as ballast.

In describing a jar, terms used for the human body are used. A jar has a foot, a body, shoulder, neck, ears/loop handles, mouth, and lip/rim.

Jars decorated with Chinese dragon and phoenix, peony and chrysanthemums, and Buddhist and Taoist symbols eventually became familiar motifs in island Southeast Asia.

Heirloom jars tell many stories of their use, in households and as ritual jars. Jars are also believed to possess some magic powers and “talk” or give a clear ringing sound when struck.

Maritime Trade

With the rise of maritime trade in the Southeast Asian region, more and more porcelains and stoneware entered the country, which early Filipinos bartered with forest and sea products.

The late Dr. H. Otley Beyer, a pioneering scholar in Philippine archaeology, had listed in 1947 every province in the country as yielding ceramic finds. The earliest ceramic wares from China had been dated from around the ninth century; stoneware jars, recovered from shipwrecks and archaeological sites or kept as heirlooms, have been dated from the 10th to the 14th century.

Fired at a higher temperature than earthenware, stoneware jars, glazed or not, remain durable and nonporous.

Around 70 percent of ceramic finds in the country are Chinese, mostly from the kilns of south China (Guangzhou (Canton), Guangdong and Quanzhou, Fujian) made for the export market; 20-25 percent are Thai, and some 3-5 percent are Vietnamese, says the National Museum.

Under the Song Dynasty (960-1279), the earliest Chinese official account in 972 pertains to Ma-i (Mindoro), together with “Arab, Achen, Java, Borneo barbarians” whose trade pass through Guangzhou, where they take away “gold, silver…silk and porcelain…”

Aside from Mindoro, early participants in island trading networks with Chinese junks included Samar, Butuan, Calamian Islands, Luzon (Manila), and the Ilocos coast.

Household treasures

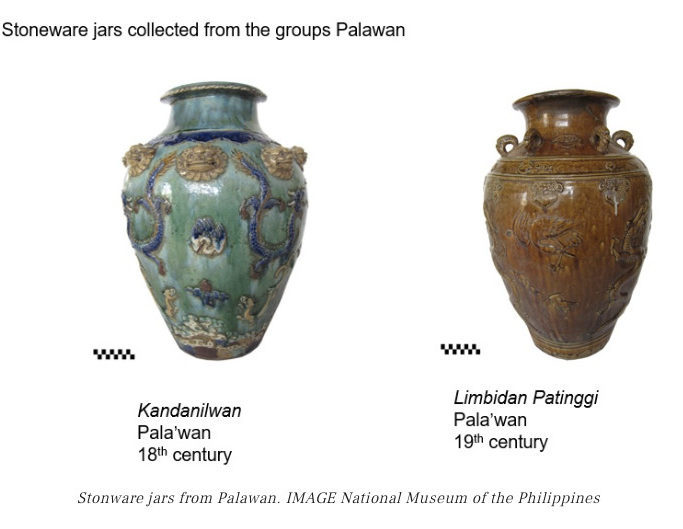

The country’s indigenous communities regard these jars as part of their family history and prized possessions, handed from one generation to the next. They have their own classification, based on design, shape, color, form and function. The Tagbanua have classified at least 24 types of jars or gusi that are only used for making rice wine. The Pala’wan have 54 types of Chinese jars and Thai jars. The Ifugao can identify 17 types of jars from China; the Bontok used six types of stoneware jars for the production of rice and sugarcane wine.

Stoneware jars were used as containers for food and liquid, for cooking, as vessels for important ceremonial rituals, and as indicators of wealth and social status.

Chinese jars are among the most valuable properties of the Ifugao, Tagbanua, and Pala’wan. They are used as containers for fermented tapuy or rice wine brewed especially for rituals related to birth, death, wedding, and thanksgiving for a good harvest.

The stoneware jars are also used in primary and secondary burials, connected with the belief in the spirit world and life after death, replacing the local earthenware originally used for burial. In some archaeological sites in Palawan, broken jars have been found on top of gravesites, connected with the tradition of pabaon or provisions for the journey of the departed into the afterlife.

Through the EYG Resource Collection, Filipinos today can rediscover and establish a precious connection with the aesthetic and functional gaze of early Filipinos.