Images courtesy of Dr. Cherubim A. Quizon and Lynda A.N. Reyes

Celebrating the country’s weaving heritage, Cherubim A. Quizon, PhD elaborated on the weaving traditions of the Tagabawa Bagobo in southern Mindanao, in a recent Zoom talk titled Red Cloth Reconsidered.

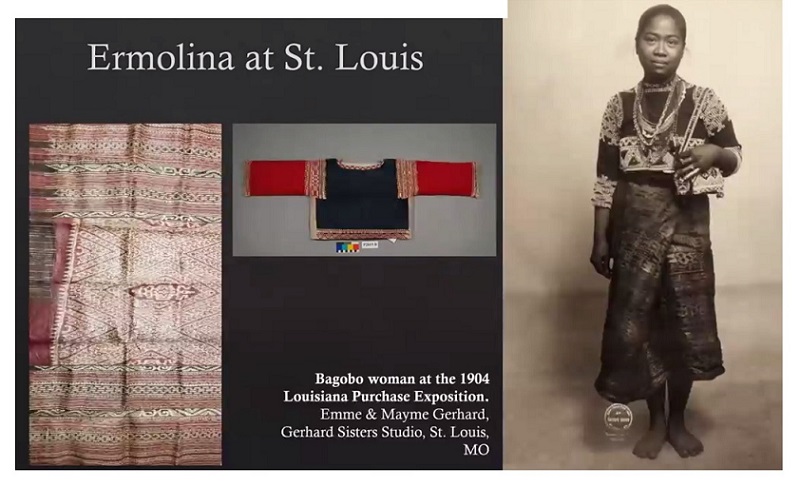

The Bagobos are one of the few indigenous peoples in the country who use the abaca plant as a material for their traditional clothing. They are also known to pay a lot of attention to their clothing and personal adornment.

Composed of three Bagobo subgroups, the Tagabawa, Klata (or Guiangan), and Ubo peoples, Bagobo territory extends from Davao Gulf to Mount Apo. Animists and nomadic in the past, their traditional rulers included chieftains (matanum), a council of elders (magani), and female shamans (mabalian).

Bagobo clothing

Bagobo men and women wear close fitting jackets that are adorned with shells, glass beads, and embroidery. Men wear knee-length trousers (saroar) usually striped and woven with bands on the hem; women wear tubular skirts (sonnod).

The Bagobos only consider a finished textile as clothing or garment. Their “most socially significant textiles” are their clothing graded according to the gender and status of the wearer, notes Dr. Quizon. They call their ceremonial dress ompák (clothing) when discussing it among themselves and kóstyom (costume) when talking to a non-Bagobo.

Bagobo inabal

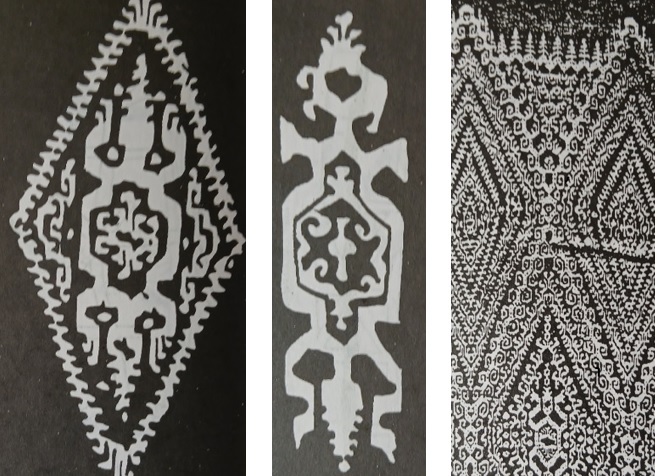

With its earth color tone, Bagobo abaca textiles or inabal (“woven on the loom”) are distinguished by its warp ikat patterns combined with black and red natural dyes from plants. It is defined by its structure and coloring of the garments, its highly polished surface, and elaborate ornamentation using embroidery, beadwork, and applique.

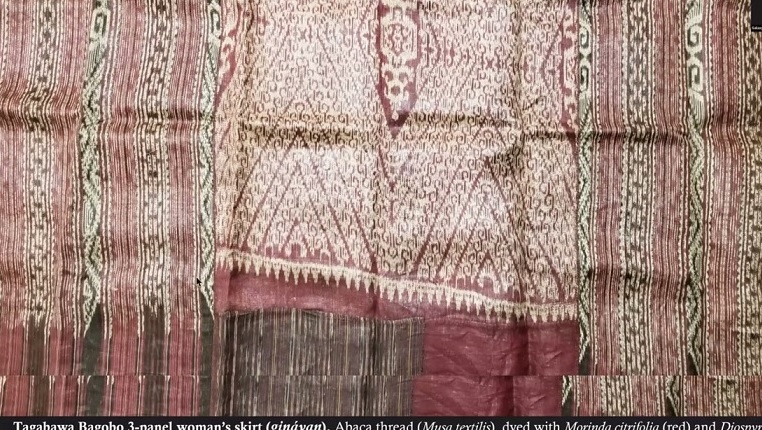

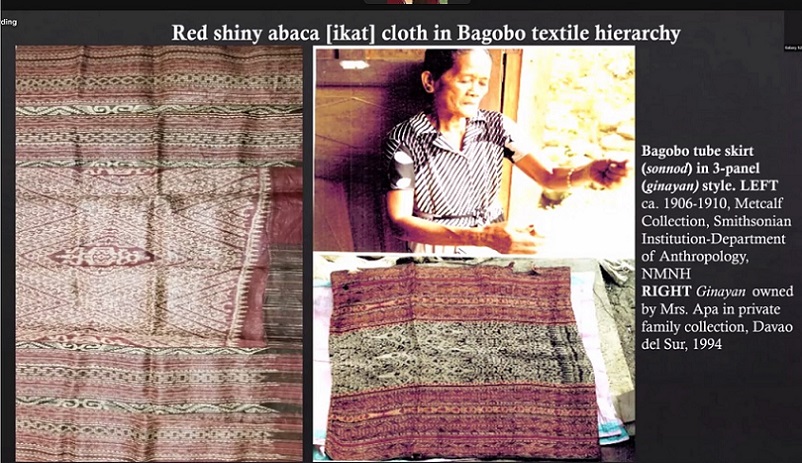

The highest status cloth with the most complex ikat patterns is made into a three-panel tube skirt called sonnod for women, dyed in red and black. The unsewn central panels or “mother” pieces are called ine or ina with two sides.

The central panel usually has figurative designs; the side panels have stylized geometric design. It takes three to four months for a master weaver to finish the inabal tubular skirts, measuring 3.5 meters by 43 centimeters.

Using a smooth shell, the finished abaca textile is polished together with beeswax to add sheen to the whole fabric.

Bagobo design

The crocodile has been a dominant design in Bagobo clothing and ornamentation, including in bags and baskets. The binuwaya (crocodile) is considered as one of the most difficult design to master and represented by horizontal lines and interlocking diamond patterns and geometric designs.

Aside from aesthetic purposes, the patterns “holds the centuries-old history, culture, identity of the Tagabawa Bagobo community.”

Ikat

The word ikat comes from the Indonesian verb mengikat, meaning to tie, knot, or bind to create ikat patterns on the fabric. It is the thread or fiber itself that is resist-dyed before woven into cloth.

The Bagobos use the warp ikat method that involves resist-dyeing only the warp threads (the fixed threads attached to the loom).

All done by hand, ikat weaving is so time consuming and extremely skill-intensive. In Bagobo society, the inabal is a symbol of wealth and status, offerings to deities, and gifts to those who perform rituals. Today, it is worn only in ceremonial occasions and treasured as heirloom pieces.

Abaca fiber

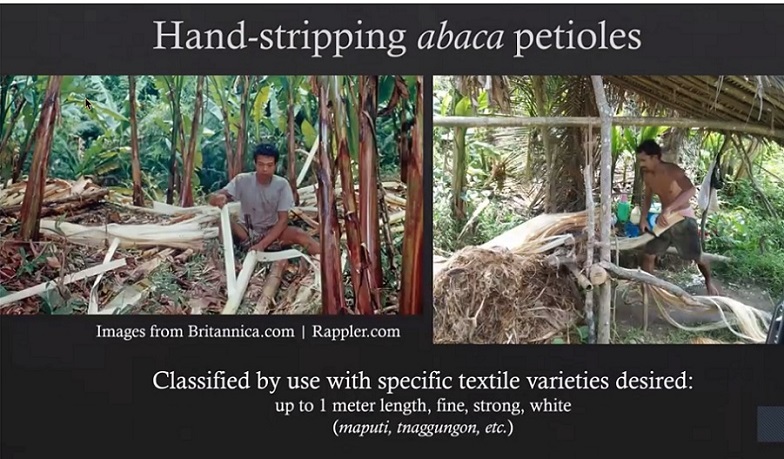

Resembling the banana plant, abaca (Musa textilis) is native to the Philippines. The fiber is extracted by stripping the leaf sheath at the bottom of the trunk.

Labor-intensive, each stalk must be cut into strips and scraped of its pulp. The fibers are washed and dried. The fiber is tied into a continuous thread and wound into a reel. The warp threads are measured and transferred to a rectangular frame.

Natural abaca fiber is white or beige in color; design patterns are left in white by overtying or wrapping with waxed threads. Immersed in liquid dye, the waxed threads resist the dye that reveals the design. The threads are then ready for the loom.

The leaves of knalom tree (Diospyrus nitida) give black and the roots of sikalig tree (Morinda citrifolia) give red. Black (metum) dyeing takes three days of continuous work; red (maloto) dyeing demands 14 days of continuous work by a master dyer. The red color is more on the maroon shade, in reality.

Cherubim A. Quizon, PhD

An associate professor of anthropology and department chairperson at the Department of Sociology Anthropology Social Work and Criminal Justice, Seton Hall University in New Jersey, United States. She studies “how ideas of nation, ethnicity and the self relate to symbols and their transformation…”. Her principal research is on the textiles and dress of the Bagobo of Mindanao.

The Department of Foreign affairs and HABI: The Philippine Textile Council are the sponsors for the heritage lecture series on Philippine traditional weaving.