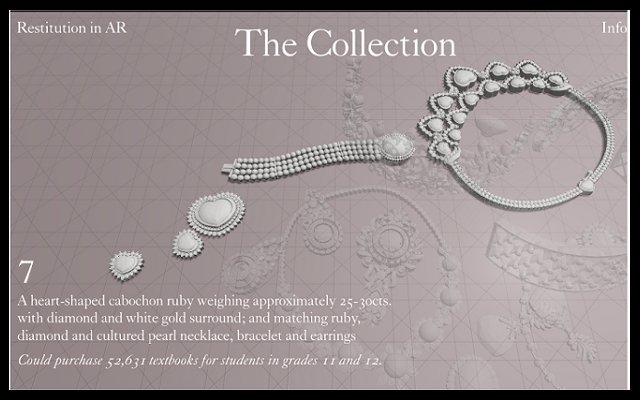

Maler, Trinidad, Rayby, Palmy, Vibur, Aguamina, Avertina, Azio, Verzo, Wintrop-Charis, Scolari – the Swiss bank accounts holder Jane Ryan had a knack for inventing swanky names to hide her identity. Those were the names of foundations that acted as fronts to receive stolen government money from 1978 to 1984 and deposit them in Swiss bank accounts. The total amount stolen was US$200 million.

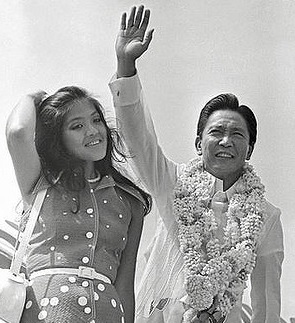

Never before in the history of the Philippines has it happened that only one person held three high government positions. From 1976 to 1984, Imelda Marcos was in her husband’s cabinet as minister of human settlements while serving as Metro Manila governor and assemblyman in the Interim Batasang Pambansa, the Marcos puppet parliament. It was also during that period that she and her husband would covertly funnel government money to their fancily named foundations to have them deposited in Swiss bank accounts.

Ten criminal cases for graft were variously filed against her in the Sandiganbayan in 1991, 1993, and 1995 for violations of Republic Act 3019, the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act. Section 3 (h) of this law prohibits public officers from holding pecuniary interest, directly or indirectly, in private business ventures, the same prohibition enunciated in the Constitution.

How were the monies sourced? They came from bribes, facilitation fees, kickbacks or commissions from Japanese corporations or suppliers of roaders and graders of infrastructure projects. The Marcos couple ordered the remittance of said monies to the Central Bank to be converted to high-interest yielding dollar treasury notes. The Marcoses then intervened in the investment placements of the Central Bank by having then siphoned to the said foundations, to the damage and prejudice of government.

Documents showed the Marcos couple issued written instructions, approved by-laws, designated beneficiaries, provided capital, wrote orders to the foundation boards to liquidate and transfer money for the couple’s benefit. Before the court, Mrs. Marcos pleaded not guilty.

In the meantime, the accused successfully had the trials delayed by requesting hearing suspensions. The trial resumed only in the year 2000. In the ensuing hearings, the prosecution presented some key Marcos men, making the evidence for the prosecution unrivalled. These were Jaime Laya (Central Bank governor during the Marcos era, among many other positions he held), and Cesar Virata (minister of finance of Marcos and later prime minister in the Marcos-designed parliament).

As for Mrs. Marcos, she did not present any contrary evidence.

The court noted that although the defense was weak, “settled is the legal principle that conviction is never founded on the weakness of the defense but rather always rested on the strength of the prosecution evidence.” The element of the crime must be proven without reasonable doubt that the accused had a direct or indirect monetary interest in the business transactions.

In some documents, Mrs. Marcos wrote orders and even marginal notes to liquidate and transfer money, and signed these not as Jane Ryan but as Imelda Romualdez Marcos. In her notes to Governor Laya, she did not consult him but “refer to your approval,” and “recommend the approval.”

The Marcoses were in a hurry to escape Malacañang on the night of February 25, 1986. Despite tons of documents they shredded (three shredding machines had jammed) and burned, still the documents they left behind were explosive. The court noted that the accused “did not interpose any objection.”

In rendering the decision, the court said that, “the constitutional right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty can be overthrown only by proof beyond reasonable doubt.” Imelda Marcos was found guilty of seven of the ten criminal charges. The decision was unanimous. She was sentenced to a minimum of 42 years to a maximum of 77 years in prison.

On promulgation day on November 9, 2018, she failed to appear in court. A week later, the Sandiganbayan 5th Division judges grilled her on her absence and noted her conflicting answers. She hovered between “I did not know the schedule of the promulgation,” to having seven illnesses, to experiencing chest pains. But where was she on promulgation day? She partied on that day for the birthday of daughter Imee, with Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, Joseph Estrada, Juan Ponce Enrile and Sara Duterte. The partying Imelda, then 89 years old, was fit for jail.

Philippine National Police chief Oscar Albayalde said Imelda was too old to be arrested. The 79-year old Ricardo Castro of Tondo wasn’t as influential. Forgetting to pay a pack of chocolates at a grocery store while preoccupied over his son’s cancer, Castro was jailed. Older than Imelda, the 94-year old Flaviana Sagapsapan was jailed for parricide in Zamboanga del Norte.

Article 13 of the Revised Penal Code says age is only a mitigating factor in criminal liability. But in 2010, the Supreme Court ruled that criminals could not use mitigation when they were below 70 years old when they committed the crime. Imelda was 57 years old when she crooned “New York, New York” inside that US military plane that brought them and their martial law co-conspirators to Hawaii in February 1986.

We are a country for aged criminals, unless you are a criminal named Imelda Marcos.

The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.