Text and photos by ELIZABETH LOLARGA

TO the military, cultural worker Artus Talastas was a terrorist. To his comrades, he was a hero.

What cannot be disputed about Talastas, who was killed in an encounter between the military and suspected communist guerrillas last June, is his imperishable Igorot spirit. It lives in works that, in Katherine Anne Porter’s words, “cannot be destroyed altogether because they represent the substance of faith and the only reality. They are what we find again when the ruins are cleared away.”

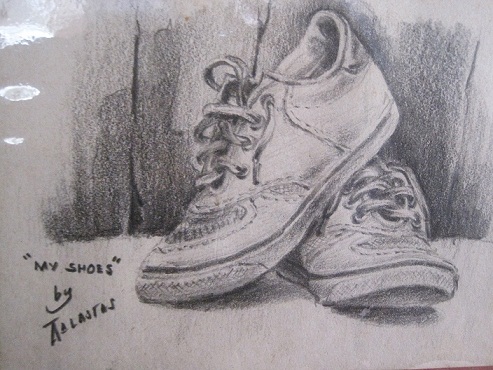

It is from this body of artworks where his widow Jane Makagni, three-year-old son Gambikan and the Cordillera cultural community draw their solace. A commemorative exhibit at the University of the Philippines Baguio Alumni Center proves the wide range of Talastas’ skills in portraiture, landscapes, still lifes, design and illustration of posters and pamphlets. Not included are ephemeral images that once went into streamers, since then folded or cast aside, and murals as backdrops for stage presentations, since then dismantled.

Adding poignancy to the show is its make-do manner of presentation. No gallery pin lights or white walls are there to enhance the look of the works. Instead, pencil drawings are mounted on illustration boards, covered in transparent plastic for protection and held up by rough strings, not even nylon ones.

If the viewer asks, his younger brother Sixto will pull out frayed sketchpads and loose drawings where Artus did compositions of a reclining nude, a Cordillera couple in tribal attire pounding rice and others.

The Talastas siblings were orphaned early, but Artus knew his father Delfin long enough to learn the basics in drawing. The older man, reportedly the first Cordilleran to graduate with a fine arts degree from the University of Santo Tomas in 1960, gave his oldest son a name akin to the word “art.”

The orphans moved from the Mountain Province to their grandparents’ home in Cubao where they spent their youth. Artus also won a two-month Piso Bank scholarship that enabled him to hone his skills under veteran art teacher Fernando Sena. He later took up civil engineering at a Quezon City institute, but was kicked out and padlocked from the school’s premises when he joined a picket protesting a tuition fee hike.

Depressed, he went to Baguio where he continued his studies, but the costs of tuition became a constraint again. Meanwhile, the fires of activism were stoked. He organized the youth around issues of indigenous people’s rights and social justice. He took in commissioned work from non-government and people’s organizations.

His social realist style was heavy in details, requiring tremendous patience. Writer Luchie Maranan noted this quality reflected in other tasks. She said, “He was tireless in his visual artistry, meticulous and patient. I saw that he was indignant over the puwede na mentality. He gave his best, poured his artistic soul into his works. Most important was his firm commitment to the cause of the struggle. He was of a totally different conviction.”

As founding member of Dap-ayan Ti Kultura Iti Kordilyera (DKK), a progressive group of cultural workers and artists, he showed this conviction in making known the musical group Salidummay’s songs of indigenous people’s suffering, struggle and victories.

Maranan, who’s in DKK’s advisory council, says, “The task was to popularize these pieces without too much bother on copyright. No wonder that the songs of Salidummay became songs of elders and children alike in the villages. They were familiar stories on the homeland that they were repeatedly played by bus and jeepney drivers and conductors plying Halsema Highway. Western country songs had to take the back seat. To this day, these songs still ignite in us the fervor and unfailingly inspire us.”

She remembers Talastas as “typecast as a village elder in almost all plays, he practically grew into that role. He had a serious mien, almost brooding, but once you bantered with him, that demeanor always melted into the comic character that he really was. He was pilosopo and funny.”

Sixto says Artus was last heard organizing people in Aguinaldo, Ifugao, to question the building of a mini-hydro project along Sifu River on account of the proponents not divulging facts on how big the dam would be, where exactly it would be built and how many rice fields would be submerged.

He adds that his manong, who became known as Ka Libre and who continued to sketch on any available paper and sign his work “Forawet,” wasn’t the sort of organizer who went to a place to just “meet and meet. His work included the arts and culture, ang pagpapalabas (to stage a show) to educate a community.”

With his life snuffed out at age 45, Talastas leaves an inspiring legacy of upholding the arts as a means to enlighten and to wage a valiant fight.