By PABLO A. TARIMAN

THERE is no sign of the music of Nicanor Abelardo in this generation of singers rattling their epiglottis away in assorted amateur singing contests mounted by several TV networks.

But perhaps ABS-CBN Philharmonic will make a difference by introducing Abelardo’s music in its educational programs.

For the new generation of music lovers, Nicanor Abelardo is just a name of the UP College of Music auditorium and the CCP main theater.

But for Filipino musicians schooled in music conservatories, Abelardo is the composer behind such immortal songs like “Mutya ng Pasig,” “Bituing Marikit” and “Nasaan Ka Irog,” among others.

Thanks to the other existing symphony orchestras and the small but significant array of classical singers, the music of composer Nicanor Abelardo still lives in school recitals and season concerts.

Born in San Miguel de Mayumo in Bulacan in 1893, Filipino composer Nicanor Abelardo would have been 120 this year.

The decade of his birth was historic. Abelardo was only three years old when Rizal was shot at the Luneta, he was only five years old when Spain ceded the country to the United States through the Treaty of Paris for a mere $20 million.

The year he was born was the same year Peter Ilych Tchaikovsky, the famous Russian composer, died.

Moreover, it was the same decade composers Sergei Prokofiev, George Gershwin (“Porgy and Bess”) and Carl Orff (Carmina Burana) were born.

Moreover, it was the same decade composers Sergei Prokofiev, George Gershwin (“Porgy and Bess”) and Carl Orff (Carmina Burana) were born.

The life and times of Abelardo is beautifully recalled in the book, “Nicanor Abelardo:The Man and the Artist.– A Biography,” by Ernesto V. Epistola.

A professional cellist and orchestra conductor and teacher at the University of the Philippines, Epistola was able to capture the composer’s life in a 121-page book full of poignant chapters from the composer’s short but prolific musical life.

As it turned out, there was no way Abelardo could escape music early in his childhood. His father, a photographer, loves music and his mother was a church singer.

Showing early musical inclination and skill, Abelardo was obviously a musical prodigy when he learned to read notes at age five and was able to play the banduria at same age.

At age six, he was playing the guitar version of William Tell Overture and at age eight, he composed his first waltz, “Ang Unang Buko.”

As Epistola recounted it, Abelardo’s life was full of struggles as he tried to make a living out of his music-making.

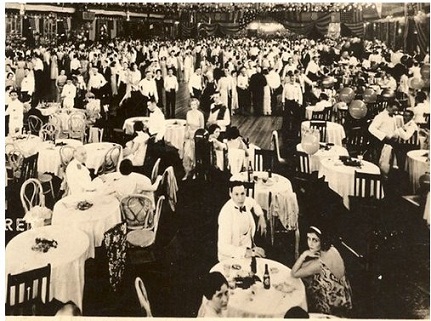

Teaching at the UP Conservatory of Music in the 1920s as head of the composition department, he caused furor in the school when he moonlighted as leader of a dance orchestra at the Sta. Ana Cabaret then being advertised as the biggest in the world. For that extra job out of his teaching load, Epistola wrote he was paid an extra P300 and then later adjusted to P600 a month.

Alexander Lippay, founder of the Manila Symphony, then director of the UP conservatory had a standing order that “no professor should engage in occupation that would be derogatory to the prestige of the conservatory.”

Alexander Lippay, founder of the Manila Symphony, then director of the UP conservatory had a standing order that “no professor should engage in occupation that would be derogatory to the prestige of the conservatory.”

Another composer, Francisco Santiago, agreed with Lippay.

The truth was Abelardo was not just teaching but also playing in cabarets and movie houses to supplement the family income. It was a hectic life and a lonely one. It led to alcoholism.

With his talent as big and as encompassing as it is, he was still sent to the Chicago Musical College for post-graduate studies and won a scholarship with his winning composition, “Cinderella Overture.”

(On October 19, 1985, the Cultural Center of the Philippines honored Abelardo when it initiated special concerts in Chicago with the Chicago Symphony playing Cinderella Overture and Mutya ng Pasig and with tenor Noel Velasco and soprano Eleanor Calbes singing selected Abelardo kundimans.)

Back in the Philippines in the early 30s after enjoying scholarship abroad, Abelardo was again hounded by financial problems and his bout with liquor worsened.

The late music critic and jazz advocate Lito Molina told this author the composer was always reeking of liquor every time he would visit his father, National Artist for Music Antonio Molina. It may be noted that National Artist Molina was in awe of Abelardo’s talent and even compared him to Saint-Saens and Schubert.

It wasn’t long when Abelardo finally succumbed to intestinal hemorrhage.

When he died in 1934 at age 41 with over 140 compositions to his credit, Abelardo was all the more reborn with his music and countless followers.

Quite a sight was co-teacher and colleague Francisco Santiago crying unabashedly on his coffin.

Moreover, the scenes from his funeral were awesome. There were three truckloads of flowers; the funeral procession –headed by the Philippine Constabulary band — was almost two kilometers long.

Biographer Ernesto V. Epistola recalled the composer’s last moments on earth thus: “There was a big crowd at the cemetery that afternoon and many people say that it could even rival the funeral of Manuel Quezon. As the coffin was lowered into the grave. The great crowed was hushed in homage and prayer.”