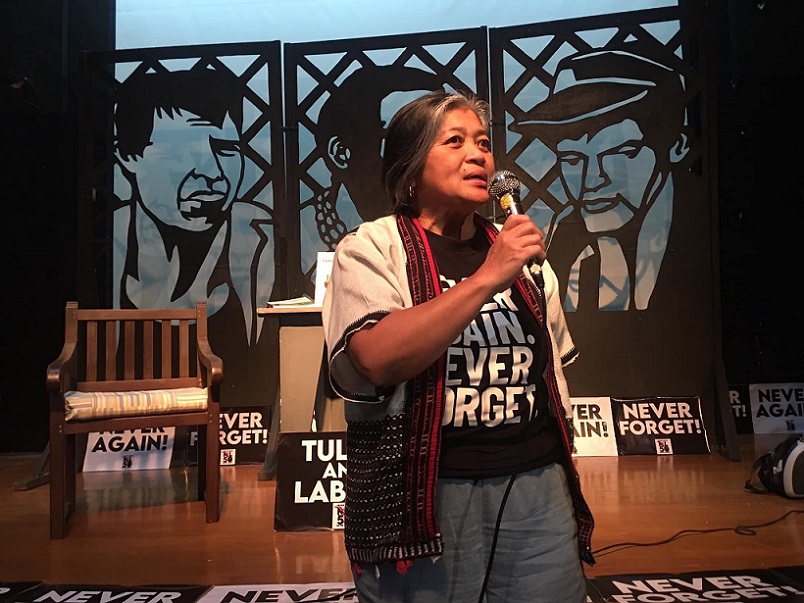

Photos courtesy of Joanna K. Cariño and Luchie B. Maranan

I blame the Marcoses for much of the ruin that our country has fallen into. It is not enough for the current president and namesake of the late dictator to say that he is doing his damn best. Let’s not even use the term “giving it the old college try” when it concerns him, he not having finished a proper collegiate course.

And let us not be shy about naming them all—from Ferdinand Junior or Bongbong to his parents, Ferdinand Sr. and Imelda, his sisters Imee and Irene, his brother-in-law Greggy Araneta, his wife Liza Araneta and sons Sandro, Simon and Vinny and their intertwined branches of relatives and cronies who have gone unpunished by a nation that they had raped and plundered to a degree that still continues to astonish the world.

From 1965 when Marcos Sr. was first elected to the early 1980s, Philippine society under him was suffering from a terrible malaise. It was rotting from within. Marcos was at the heart of it all. Marcos and his cronies grabbed from the old oligarchy all the riches they could lay their hands on. Meanwhile, the middle and lower middle classes witnessed this without raising an open protest and found nothing wrong about appropriating what they also could for themselves. As for the masses who we were supposed to be fighting for, what the hell!@#? Everybody else, especially the leaders, was doing it, so who was going to stop us now?

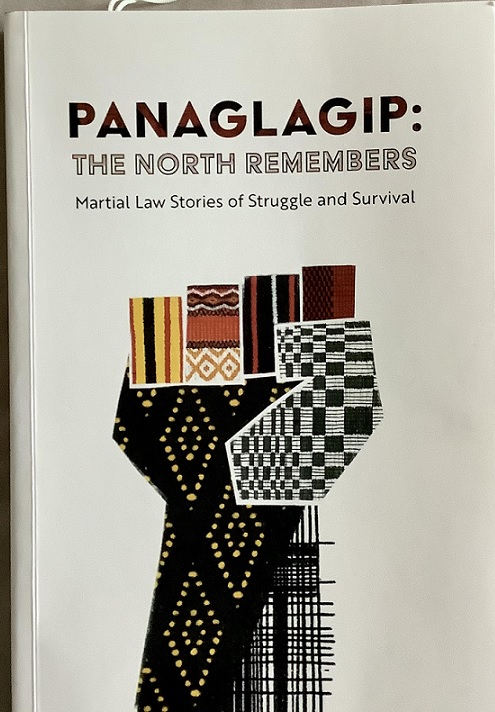

Reading through Panaglagip: The North Remembers—Martial Law Stories of Struggle and Survival, published by Gantala Press and Alfredo F. Tadiar Library with the support of the May 18 Memorial Foundation and PROCESS or Participatory Research, Organization of Communities and Education Toward Struggle for Self-reliance, one relives the traumas faced by our generation and that of our parents when we all woke up one fine September morning in 1972 to find ourselves stripped of our basic freedoms and rights, to later discover that our school organizations, even seemingly harmless ones like the Sodality or Student Catholic Action, had been banned, that some friends and acquaintances had gone underground or worse, picked up, imprisoned, tortured or summarily killed, their bodies thrown in unknown graves.

Summary killings, also known as extra-judicial killings or EJKs, were not a Duterte phenomenon; they were practiced widely during the Marcos Sr. regime. As we know, Duterte was quite public in acknowledging that Marcos was his idol in wielding the kamay na bakal or iron fist.

Northern Luzon was not spared even if Ilocos Norte was the Marcoses’ home province and turf. In fact, Northern Luzon formed an admirably brave phalanx of resistance against the forces of authoritarianism. Out of that oppressive climate a hero such as Macli-ing Dulag emerged after he led the resistance against the World Bank-funded Chico River Basin Development Project that intended to flood lands owned by the indigenous people, specifically the Kalinga and Bontoc tribes, to make way for hydroelectric dams.

As editor Joanna Cariño wrote in “The Popular Resistance against the Chico Dams and Martial Law,” “The…dictatorship did not reckon with the strong communal ethos still existing then among the Bontok and Kalinga, which allowed them to forge strong unity among the…peace pact-practicing villages along the Chico river in opposition to the project. The Marcos dictatorship did not reckon that these long neglected indigenous communities were capable of total tribal mobilization fetad in defense of life, land and honor.”

Damn the dam indeed, that was what Macli-ing Dulag, a tribal leader, did at the cost of his life. Earlier, Manuel Elizalde, a member of the Marcos Cabinet, tried to bribe him with a thick envelope. Macli-ing told the mestizo Elizalde to his fair face, “This envelope can contain only one of two things—a letter or money. If it is a letter, I do not know how to read. And if it is money, I do not have anything to sell. So take your envelope and go.”

If anything, that’s the best break-up line I’ve ever come across. It beats Groucho Marx’s “Go, and never darken my towels again!”

Levity aside, the book also narrates through prose, poetry and artworks what some of the contributing authors had been through and are still going through because of closure issues. But why seek closure indeed? After all, the criminals, specifically the Marcoses, remain unrepentant, lying through their teeth and nose jobs that human rights violations were imagined transgressions.

Poet Luchie Maranan relives in her poem “News from Abra” the murder of another defiant one with children as collateral damage.

The mountains were giant shadows

Seething, watching

When they ended your life in the fire,

While you coddled your four-year old child, Josefina.

Bitter, copious tears flowed in the shadows

Questioning the darkness of the forest

Saying goodbye to the unborn

Whose life was ended in the mother’s womb

Tomorrow or the day after, the earth

That embraced the beloved mortals’ dust

Shall be honoured.

Apart from Cariño and Maranan, the other contributors to Panaglagip are Ma. Cristina V. Rodriguez, Liza Ann Ilagan, Brenda Subido-Dacpano, who also recreated scenes from prison cells through her paintings and drawings, Reynaldo Guillermo, Lenville C. Salvador, Mary Lou O. Marigza, Elina M. Velasco-Ramo, Romella Liquigan, Felicidad Valencia, Pilar V. Paat, Lina Ladino, Wilson Adorable, Maureen B. Loste, Rudy D. Liporda, Jill K. Cariño, Jeoff Larua, Kathleen Okubo, Priscilla Supnet-Macansantos, Ruel D. Caricativo, Desiree Caluza and Christian Patricio.

They are the writers, the artists who dared to relive and remember the excesses of martial law. They are like the survivors of another series of crimes against humanity—China’s Cultural Revolution. These Filipinos have produced our very own poignant Literature of the Scarred, the Literature of the Wounded.

The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.