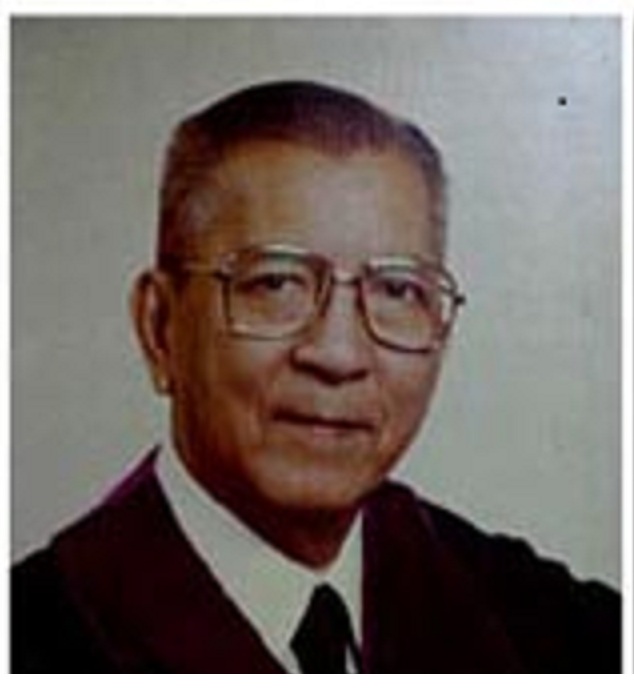

Enrique Medina Fernando was, by all indications, destined to be an imposing Filipino.

Born in Malate, Manila in 1915, he graduated secondary studies from the Manuel Araullo High School, one of Manila’s oldest. He then went to the University of the Philippines for college. In 1938, he completed Bachelor of Laws, graduating magna cum laude as valedictorian of his graduating class. Classmates’ recollection of him was unanimous — one of the bright students in class. On that same year, he passed the bar by landing 13th place.

Fernando then went straight ahead into teaching full-time at UP Law. At UP, he developed a reputation as a terror in the classroom. It was the same at the Lyceum of the Philippines where Sotero Laurel had invited him to teach constitutional law. His Lyceum students at one time went on strike against him.

Yet it was in academe that a reputation as a consummate academician preceded him. Many of Fernando’s students emerged as prominent justices and legislators. Among them were Senator Ambrosio Padilla, Vicente Abad Santos the Secretary of Justice and Supreme Court Associate Justice, and Ramon C. Aquino the 15th Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.

Later in his judicial career, he was considered a mentor by such legal luminaries as Chief Justice and Senate President Marcelo Fernan, Associate Justices Teodoro Padilla, Florentino Feliciano, Hugo Gutierrez, Flerida Ruth Romero, Isagani Cruz, and Camilo D. Quiason.

Teaching full-time at UP Law until 1953, the university would later grant Fernando its prestigious professorial chair for the George A. Malcolm Professor of Constitutional Law.

Nine years after becoming a lawyer, in 1947, he went to Yale University for his Master of Laws. He was the first Filipino to become a Sterling Fellow at Yale. For a Sterling Fellow at Yale, the university provides a stipend for the student to pursue careers in public service and social justice. Fellows are selected based on their academic records. He was thus, in the catchall traditional name of Yale alumni, a full-pledged Yalie.

Back in the Philippines, the Yalie Fernando put to good use a budding career in public service. In the 1950s, he served as presidential adviser to two presidents, Ramon Magsaysay and Carlos P. Garcia. He also went full swing in his private law practice. Among his law partners was Sen. Lorenzo Tañada. With the grand old man Tañada, Fernando would author a book on constitutional law.

Constitutional and administrative law became his legal specialty in his teaching and practice. Fernando would go on to author thirteen law books, some of which he co-authored with his wife, the lawyer Emma Quisumbing Fernando.

Justice Isagani Cruz, who wrote a regular op-ed column in the Philippine Daily Inquirer, wrote of Fernando: “He was more knowledgeable than many American lawyers in their own jurisprudence on the subject and could quote from memory Justices Holmes, Cardozo, Brandeis and other eminent jurists.”

Fernando also became an active member of the Civil Liberties Union together with Jose W. Diokno, Claudio Teehankee and other libertarians.

In 1966, the dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr. appointed Fernando as presidential legal counsel. They were fraternity brothers in Upsilon Sigma Phi. One year later, Marcos appointed him associate justice of the Supreme Court. One of his colleagues in the Supreme Court was the brilliant civil libertarian JBL Reyes who was actually the founder of the Civil Liberties Union. His Yale background and his brush with these distinguished civil libertarians gave Fernando a noted reputation on republicanism and individual rights.

In the Morfe vs Mutuc case of 1968, the statement of assets and liabilities required of every public officer each year as set in the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act of 1960 was challenged in court as “violative of due process as an oppressive exercise of police power.”

Fernando wrote for the High Court otherwise, that obligating a public official to submit annual sworn statements of financial conditions, assets and liabilities is part of the “discharge of public trust.” He said, “The private life of an official cannot be segregated from his public life.” It was a statement on good governance by way of clean public service that remains relevant today.

In the Gonzales vs Comelec case of 1969, the petitioners challenged the Revised Election Code of RA 4880 prohibiting the early nomination of candidates and limiting the period of partisan election campaigns. The petitioners invoked the basic liberties of free speech and free press, freedom of assembly and freedom of association.

The amicus curiae was Senator Lorenzo Tañada who justified the enactment as under the clear and present danger doctrine, “the substantive evil of elections, debased and degraded by unrestricted campaigning, excess of partisanship and undue concentration in politics with the loss not only of efficiency in government but of lives as well.” Expressed in shorthand, election campaigns were dirty. In his ponencia, Fernando cited Tañada, in the end declaring that the election regulations were not unconstitutional.

Justice Isagani Cruz would later write superlatives of Fernando: “He was one of the most erudite members of the Supreme Court, an uncompromising libertarian and a staunch defender of the democratic ethic.”

In 1979, dictator Marcos elevated Fernando to the post of the 13th Chief Justice of the land. He served for six years until 1985. And then his star began to wane in ambiguity. If his court colleague Claudio Teehankee was a consistent dissenter to the martial law rule of the dictator, Fernando was otherwise. He frequently voted to affirm the Marcos martial law when challenges against it were brought before the court. He made attempts to qualify his opinions with the Bill of Rights, but it turned futile. The Supreme Court under him was popularly perceived as a “lackey of Malacañang.”

And then one day the public validation of that perception happened. Chief Justice Enrique M. Fernando was photographed holding an umbrella for the Madame Conjugal Half of the dictatorship. The public did not see it as chivalry. They saw it rather as Fernando’s final act of legitimizing the conjugal dictatorship of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos.

Supreme Court jurists, by tradition, are highly regarded in the Philippines as agents of public accountability, brokers of good governance, purveyors of the rule of law. All that evaporated in forgotten mist under Imelda’s parasol. Tacit approval for tyrants is the refuge of scoundrels.

Listen and take heed, civil libertarian and environmental warrior Marvic Leonen. This too may become your fate one day.

The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.