(First of two parts)

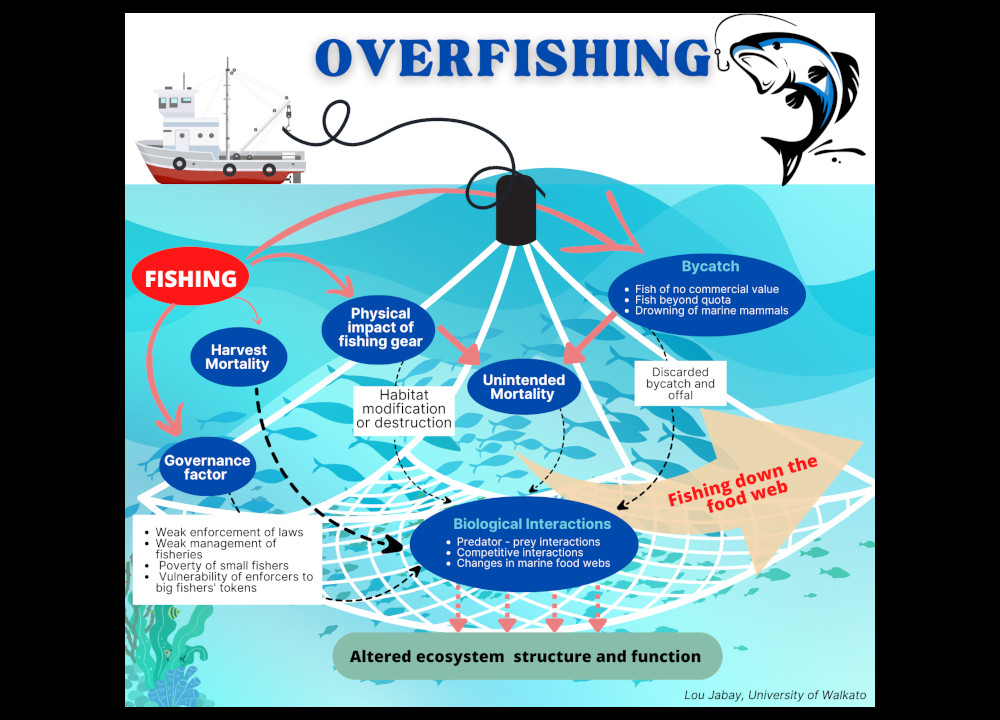

Anda, Bohol — At dawn, the turquoise waters off Lamanok Point glint like glass, hiding a story of recovery beneath the waves. For years, these waters off Anda, Bohol, were slipping into silence. Overfishing, mangrove deforestation, coral damage from blast fishing, and pollution from the upland runoff have severely degraded one of the Philippines’ richest marine ecosystems.

But today, that has changed. Through community-led efforts that blend indigenous knowledge and science, Anda’s coast is showing signs of rebirth. Marine life is returning. Coral cover is improving. And fisherfolk are once again finding sustenance at sea.

Known for its white sand beaches and cave pools, Anda town features a rich marine ecosystem teeming with live hard coral cover, macro benthic invertebrates, and five marine protected areas (MPAs). But its story goes deeper. The town also holds an archaeological complex — famous for its ancient petrographs on rock shelters, boat coffins, burial jar artifacts and sacred shaman cave — that offers a cultural anchor for a new kind of conservation.

With a population of just 18,000 (Philippine Statistics Authority, 2020) the town made significant strides in addressing marine ecosystem decline through a “ridge-to-reef” approach. The strategy protects the entire watershed, from upland forests to coastal reefs through a coordinated effort involving local government units, stakeholders, government agencies, and people’s organizations.

“We realized our life, food, and future all depend on the health of the ocean,” says Dario Gultiano, president of the Badiang Fishermen’s Association-Lamanok Badiang Association (BAFIAS-LABAS), a people’s organization (PO) comprising some 60 local fishers, women and community elders, at the forefront of marine protection in this town.

Lamanok Point is an archaeological site in the northeastern part of Bohol that lies adjacent to the Badiang Fish Sanctuary.

The strategy involving the closing of 15% of the fishing grounds to human activity to allow fish stocks to accumulate biomass, including biodiversity, sought to keep a balance of ecological and human well-being priorities through effective fisheries governance, and recognizes the interdependence of land and sea, explains Gil Gultiano, officer-in-charge of Anda’s Municipal Agriculture Office-Coastal Resource Management (MAO-CRM). “It includes everything from solid waste management, mangrove forest protection, to coral rehabilitation,” he says.

Among the early signs of recovery, fisherfolk like Mancio and Fernando Ligutan now catch as much as 16 kilos of danggit (rabbitfish) and katambak (snapper) on good days using traditional “pukot” or fish nets.

“The fishers’ life is a ‘hit or miss’ (tsamba-tsamba) thing, sometimes you have a catch, sometimes you don’t have any,” Fernando says, but adds that “the sanctuary nearby is a great help, now we are assured that there will be fish, and we don’t have to go far. For that, I’m thankful.”

From Destruction to Protection

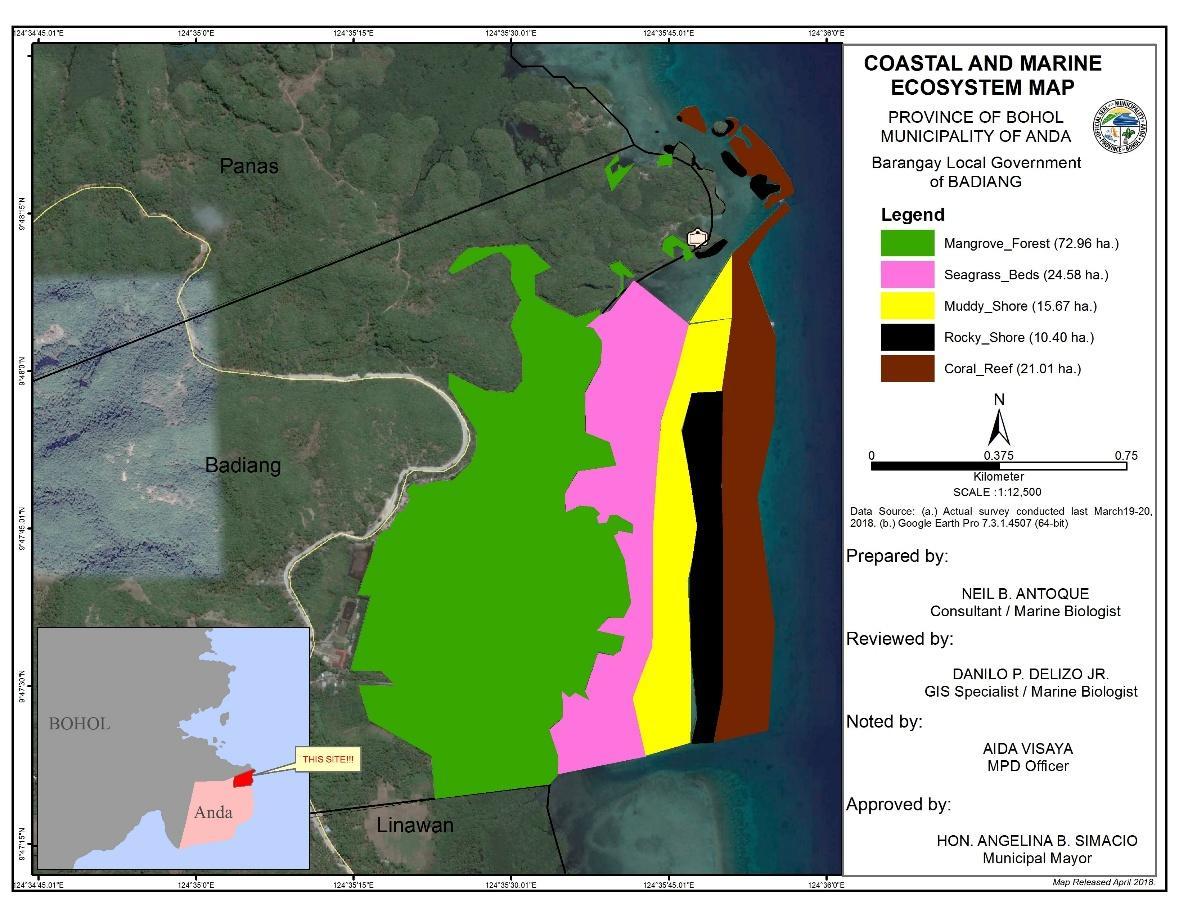

Anda’s journey to sustainability began in 2004 with the establishment, through Barangay Ordinance Series of 2004, of the 70-hectare Badiang Marine Sanctuary, following reports of declining fish stocks and coral degradation.

“At that time, one could hardly see any big fish,” recalls Fortunato Simbajon, 68, one of the original local tour guides. “Corals were damaged in Badiang and other parts of Anda then due to blasting and other destructive fishing involving poisoning, while mangroves were harvested by ‘dayo’ or outsiders for firewood and housing,” he narrates, and shares that he was one of those Bantay Dagat (sea wardens) absorbed to be part of BAFIAS.

Former maritime policeman Fidel Amora Castrodes, now Badiang’s barangay chairman, considers law enforcement through sea patrols as a main function of the local government in protecting MPAs. “Law enforcement is critical. We have to protect the area through patrols and community enforcement. For big violators, we sometimes need back-up support of the Coast Guard Station,” he states.

The barangay LGU deploys two Bantay Dagat that patrol the sanctuary at night, while the PO keeps watch during the day.

When the ordinance making Badiang a Marine Protected Area was implemented, “there was fear of the deprivation of the rights of fisherfolks who initially resisted the move,” according to municipal tourism officer Ruvien de Guzman. “They feared losing access, but after clarifying the role of MPAs during public hearing and consultation meetings, and when they saw more fish later, support grew.”

Today, the Badiang MPA has a core site with coral reefs and seagrass beds. It lies near a 115-hectare mudflat where a naturally grown mangrove forest estuary and established plantations are managed as protection against strong winds and to serve as habitat for fish and other marine life, as well as for nature tours, Gil Gultiano shares.

The buffer zone serves as the place where fishing is allowed, but only for specified safe or sustainable fishing methods–hook and line, spear hunting, single net fishing, and snorkeling, says Bantay Dagat member Rico Pitlo.

“The idea of the MPAs is for the fish and other benthic species to base there, and reproduce, so that fishers can have livelihood in the process, while conserving marine life and allowing corals to recover,” explains Jaymon de la Peña, an environmental management specialist.

Empowering Communities

Local organizations like BAFIAS–LABAS play a central role, managing eco-tours, guiding visitors through mangroves and sacred caves, and enforcing sustainable practices. “It’s not just about conservation,” says de Guzman. “It’s about empowerment and building livelihoods.”

The group entered into a Protected Area Community-Based Resource Management Agreement (PACBRMA) with the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) in 2006, formalizing its role in environmental stewardship.

Today, members serve as tour guides, boat operators, and conservation educators. Their “mystic experience tour” of the Lamanok Archaeological Complex blends cultural heritage with environmental education.

Anda now boasts five MPAs, each co-managed by local POs. The Linawan sanctuary is supported by a mostly women-led group; the Suba and Candabong MPAs collaborate with the Bohol Island State University (BISU)-Candijay on coral restoration and giant clam monitoring.

MPAs have made a measurable impact, says Villa Pelindingue of the Bohol Provincial Environmental Management Office (BPEMO).

Climate change remains a threat, particularly to coral reefs, but “these sanctuaries give ecosystems a fighting chance,” says environmental management specialist Jaymon de la Peña.

Scientific support from academic institutions like BISU-Candijay and private partnerships, such as with Amon Ini Resort, help sustain restoration efforts. Coral nurseries have been established, and mangrove reforestation is ongoing.

“Planting mangroves with upland and coastal volunteers not only protects against storm surges but enhances fish habitats,” says de la Peña.

Amon Ini Resort assists in the management of a pilot demonstration site for coral restoration system in Candabong village by training its staff and divers in planting and nursing corals under BISU marine biologists and providing technical support in record keeping and growth performance monitoring, says Arne Bernal, the resort’s social media coordinator.

Meanwhile, enforcement remains tight. “No fishing is allowed in the core zone. Only sustainable methods are permitted in buffer zones,” Gil Gultiano explains. Equipment like triple nets and fish traps are restricted to protect juvenile fish and fragile corals.

Fishers Turn Guardians

Fisherman tour guide Simbajon, now a grandfather taking care of four grandchildren, recalls the past 20 years with clarity. “Before the sanctuary, we had to ask upland farmers for ‘pao’ root crops or do menial jobs just to eat. Now we have fish, tours, and livelihoods.”

De Guzman agrees: “MPAs are not just environmental tools; they are poverty reduction mechanisms.”

Monthly and quarterly meetings between the municipal government and local groups ensure accountability and equitable sharing of tourism fees — 40% to people’s organizations, 60% to the LGU. The 26 dive spots in Anda are monitored, and sea turtles, like the 123 hatchlings released in October 2024, are part of the conservation success story.

Looking Ahead: Community-Driven Conservation

Anda’s marine success story is built on a multi-sectoral collaboration involving local government units, community groups, national agencies like the DENR and the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources, provincial offices like BPEMO, academia, and private partners.

“We cannot realize protection without the people’s organizations ((POs),” says Gil Gultiano. “They are our frontliners.”

Anda’s conservation journey is rooted in strong community participation and a holistic ridge-to-reef approach, which links upland and coastal ecosystems.

According to Gultiano, collaboration among LGUs, NGOs, people’s organizations, and private resorts has been pivotal, adding that the strategy addresses root causes of degradation and brings everyone to the table.

Tourism has become both an economic alternative and a conservation tool. “The eco-tourism model in Lamanok Complex promotes cultural heritage while conserving marine life,” says Anda Tourism Officer de Guzman.

Sustainable agriculture and waste management practices, such as Anda’s “no segregation, no collection” policy, have further minimized land-based pollution, according to environment management specialist de la Peña.

The town’s eco-tourism model has gained recognition. In 2020, the Lamanok Archaeological Complex was declared an Important Cultural Property by the National Museum of the Philippines, and in 2023, it was included among the geo-sites of the Bohol Island UNESCO Global Geopark.

Anda’s experience shows that when science, policy, and indigenous wisdom converge, the ocean can heal—and with it, the communities that depend on it.

“We treat the land as part of the ocean,” says de la Peña. “This is how we protect both.”

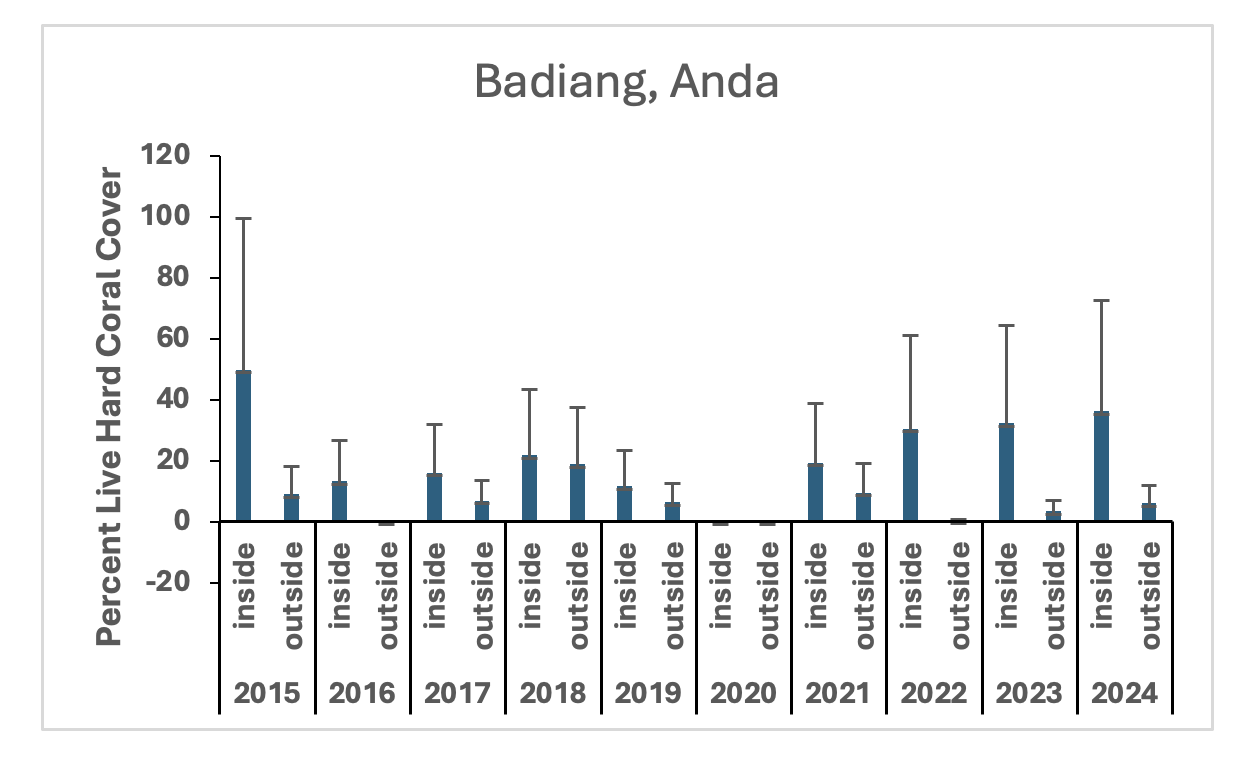

Marine Sanctuary Shows Modest Gains Amid Climate Threat

While community-led efforts and environmental programs in Badiang Marine Protected Area have yielded measurable gains, underwater assessments released by BPEMO in June, 2025, confirm that climate change continues to take a heavy toll on the area’s coral reefs, fish populations, and marine biodiversity.

According to Villa Pelindingue, head of the Coastal Resources Management Division at BPEMO, annual underwater surveys from 2015 to 2024 have revealed disturbing trends directly tied to climate-induced events.

“In 2015, coral cover inside the MPA was relatively high at 49.8%,” she said. “But by 2019, it dropped dramatically to 11.7%, indicating severe reef degradation.” Data collection in some years was disrupted—by a storm surge in 2016 and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

Figure 3. Percent coral cover of Badiang inside and out MPA from 2015-2024 (BPEMO, 2025).

Figure 3. Percent coral cover of Badiang inside and out MPA from 2015-2024 (BPEMO, 2025).

Between 2022 and 2024, coral cover showed modest recovery, increasing from 3.3% to 6%. However, the damage caused from 2016 to 2021, particularly outside the MPA, was extensive, the BPEMO report revealed. “Super Typhoon Odette (Rai) in 2021 had a severe impact,” Pelindingue emphasized. “Outside the MPA, coral cover fell to just 0.3% in 2022 before rising to 6% by 2024. This shows the vulnerability of unprotected reefs.”

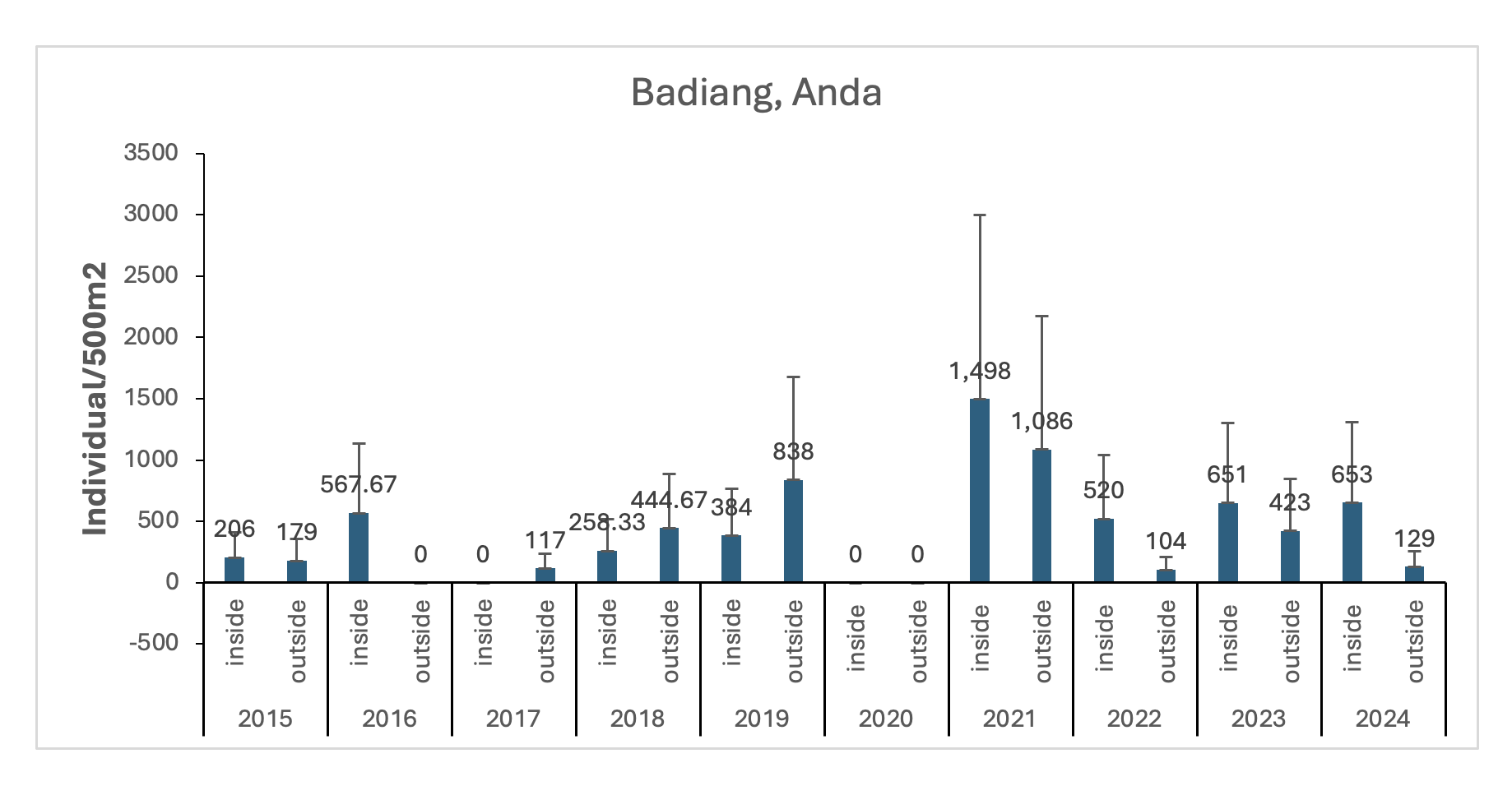

Declining Fish Density and Species Richness

Fish visual census data echo the same narrative. In 2021, fish density within the MPA peaked at 1,498 individuals per 500 sqm, but plummeted to 520 in 2022. Outside the MPA, the drop was even steeper—from 1,086 individuals in 2021 to just 104 the following year.

Figure 4. Species Density of Badiang MPA in year 2015-2024. (BPEMO, 2025)

Figure 4. Species Density of Badiang MPA in year 2015-2024. (BPEMO, 2025)

“This significant decline is attributed to the damage caused by Typhoon Odette, which severely impacted coral reef systems in Anda,” Pelindingue explained. “The storm destroyed marine habitats, triggering a loss in marine life.”

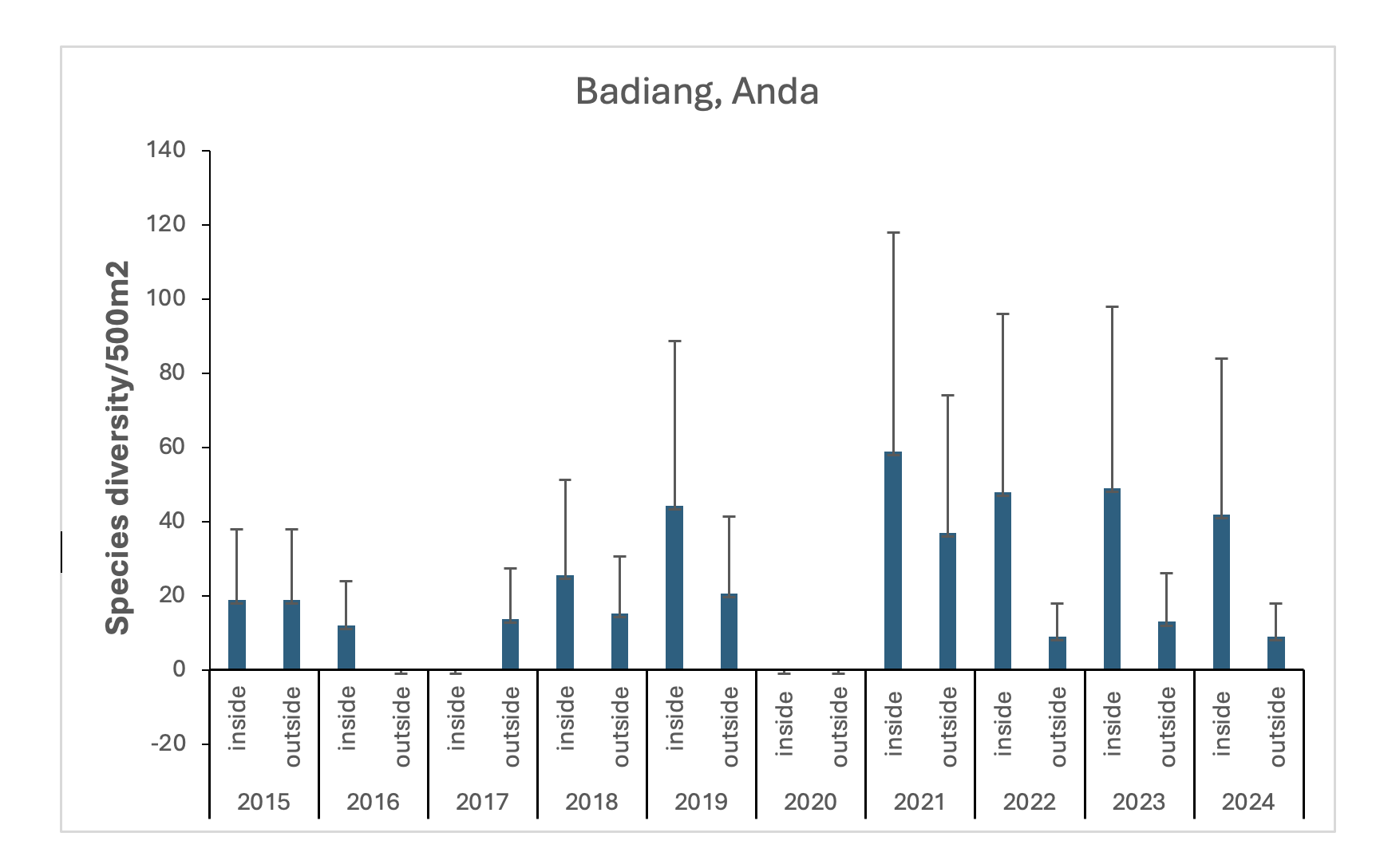

On species richness—a vital biodiversity indicator—non-target species, particularly damselfish, consistently showed higher variety throughout the survey period. The year 2021 marked the highest species richness with 59 species per 500 sqm, followed by similarly moderate levels in 2022 and 2023.

Figure 5. Species Diversity of Badiang MPA in year 2015-2024. (BPEMO, 2025)

Figure 5. Species Diversity of Badiang MPA in year 2015-2024. (BPEMO, 2025)

Macro benthic organisms also saw fluctuations. In 2021, species richness of macro benthos inside the MPA reached 29 species per 100 sqm. Density peaked in 2017 at 389.3 individuals per 100 sqm, with 2021 following at 336 individuals.

Benthic invertebrates are essential—they filter plankton, serve as food for fish, and help maintain sediment health, noted the BPEMO report.

Despite the robust marine assessments, water quality monitoring remains absent. Pelindingue stresses its urgency: “We need to monitor pH, temperature, dissolved oxygen, and coliform levels in coastal areas like Anda to better understand threats like fish kills.”

Biodiversity Highlights

An earlier biodiversity study of the Biodiversity, Coastal, Wetlands and Ecotourism Research Center (ERDB-BCWERC) in 2015-2016 recorded 19 mangrove species from nine families, and 12 beach forest species from 11 families between Barangay Badiang and Lamanok Point.

“Among mangroves, Bakauan Lalaki (Rhizophora apiculata) had the highest importance value, followed by Bungalon (Avicennia marina) and Bakauan Bangkau (Rhizopora stylosa),” the report stated.

Faunal diversity remains low, with 30 bird species, seven bat species, and one endemic Philippine macaque recorded.

There are resident manta rays, stingrays and some dolphins in the area and are protected in Anda, according to MAO-CRM Officer Gultiano. These include giant clams and green marine turtles which lay eggs on some of the beaches.

Whale sharks have been observed to follow under fishermen’s boat, says barangay chairman Castrodes.

Divers also find other diverse marine life, including pygmy seahorses, blue-ringed octopus, hairy frogfish, tiger shrimp and over 200 species of nudibranchs.

Status of MPAs in Bohol

Since 2002, the province of Bohol has established 186 marine protected areas, but their functionality remains uneven, according to marine conservation officer Pelindingue.

Of the total, 84 MPAs are still in the early stages of establishment, while 33 have made progress in enforcement and regular patrolling. Eighteen MPAs have reached the sustaining age, marked by consistent maintenance and the achievement of core conservation objectives.

Only one MPA has attained full institutionalization, operating independently with its own funding and management systems.

Meanwhile, nearly half of all MPAs are currently inactive, with plans underway to reactivate them by 2025.

Well-managed MPAs often demonstrate strong political leadership that express political will in enforcing conservation policies, community involvement, and effective networking among stakeholders, expert observers note.

Regional Collaboration and Capacity Building

Anda is part of DUGJAN—comprising Duero, Guindulman, Jagna, and Anda—a network of four municipal LGUs created to coordinate protection of 26 MPAs. Efforts include harmonizing management, increasing surveillance, and sourcing funding.

Academic partners like Bohol Island State University and agencies such as BFAR and DENR have provided vital support. BFAR’s assistance includes boats, passive fishing gear, aquaculture training, and post-harvest training and tools for groups like BAFIAS, according to Jona Rhen la Fuente, BFAR-Bohol officer.

Women’s groups have also benefited from livelihood training in food processing and basket-making, while youth and private groups lead monthly clean-ups and reef campaigns. There are also efforts to train POs on financial literacy.

“This model has moved from mere compliance to true co-ownership,” de Guzman explains. “From rules to relationships to empowerment.”

Ongoing Challenges and Way Forward

Illegal fishing, tourism pressure, and climate change continue to test the resilience of Anda’s marine ecosystems.

“Super Typhoon Odette, the 2013 Bohol earthquake, and rising sea temperatures—up to 29.7°C—have stressed coral reefs, giant clams, and other species,” says Pelindingue.

Additionally, weak institutional support, limited budgets, enforcement lapses including limited community awareness and participation, undermine long-term MPA viability, independent observers note.

Experts from the provincial environmental office agree that a formal provincial ordinance to support the DUGJAN network is needed for institutional permanence. The Lamanok Heritage Management Initiative (LAHMI), an independent heritage research and planning team, has urged the reactivation of dormant MPAs in Bohol with provincial targets and local support, and the increase of funding and training, including for enforcement and incentives.

The team also sees the need to integrate more climate adaptation strategies — like mangrove buffers and coral restoration with heat-tolerant species — and include water quality monitoring in MPA programs, integrate climate data monitoring in MPA management, and sustain community benefits through eco-tourism and equitable resource sharing.

A Model for Coastal Resilience

Anda’s ridge-to-reef initiative has become an example of integrated, community-based marine conservation.

“Other towns are now observing Anda’s model,” notes Athena Vitor of LAHMI. “It’s a living case study on how to fight overfishing, pollution, and biodiversity loss with limited resources but strong cultural grounding.”

“Coastal protection must be holistic. We must protect the whole — from ridges-to-reefs — because the coast’s health depends on the people who live closest to it, and who care for it most,” de la Pena says.

READ Part 2: Ancient Beliefs Guide Modern Conservation in Anda’s Lamanok Eco-Tours

This story was produced with support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.