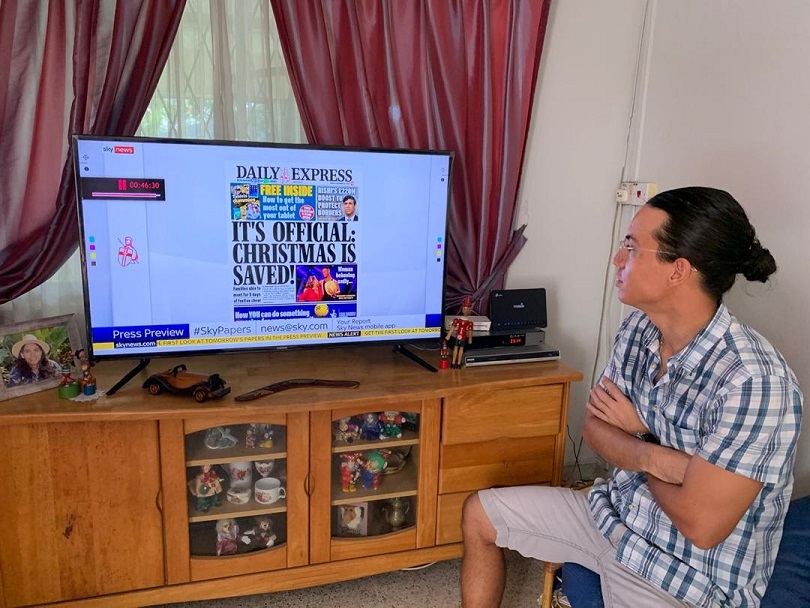

The first thing Yannik Anuar, a 31-year-old news junkie, does when he wakes up is watch Sky News, a British news channel.

“Although Britain is about 10,000 kilometres from Malaysia, I am more in tune with the British response to the Covid-19 pandemic,” said Yannik, who studied law at the University of Northumbria in Newcastle Upon Tyne, Britain from 2011 to 2013. He now lives in Kota Kinabalu, capital of the Malaysia’s eastern state of Sabah. (Editor’s Note: The Philippines continues to claim ownership of part of Sabah.)

After his coffee is brewed, he flips through the ‘Daily Express’, a local newspaper in Sabah, to get an update on the pandemic locally and nationally, while keeping Sky News on.

Throughout the day, the news junkie checks ‘The Star Online’ and ‘Malay Mail’, two of his favourite Malaysian news portals, for the latest news on the pandemic. For breaking news, he watches Astro Awani and Bernama TV, which are television news channels in Malaysia.

Yannik does not get any information on COVID-19 from social media. He ditched Facebook, Instagram and Twitter two years ago after reading the bestseller ‘Digital Minimalism: Choosing a Focused Life in a Noisy World’, written by Cal Newton, a professor in Georgetown University in the United States.

“I wanted to declutter my mind because of information overload and too much ‘fake news’ from social media,” Yannik said.

His other source of news is WhatsApp.

However, Yannik is careful about the information he gets from the messaging app as he calculates that 2.5 out of 10 ‘news’ items there are fake. For example, a video clip of an unknown ‘expert’ falsely claims that 5G technology was responsible for the rapid spread of COVID-19.

Through its Sebenarnya.my portal that has been tracking debunked ‘fake news’ items since 2017, the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC) found that 14 percent of ‘fake news’ it has come across are health-related. These include false claims connected to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Misinformation, as well as disinformation such as these, thrive in the current infodemic that has set in alongside the pandemic. Merriam-webster.com defines an infodemic as “a blend of ‘information’ and ‘epidemic’ that typically refers to a rapid and far-reaching spread of both accurate and inaccurate information about something, such as a disease”.

Digital diet

But because Yannik had, earlier on, chosen to stick to a digital diet on social media and technology, the misinformation and disinformation that came with COVID-19 have not infected him.

He is the exception – and not the rule – in Malaysia.

Many Malaysians don’t know how to identify ‘fake news’, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman (UTAR) journalism lecturer Teh Boon Teck says.

Surveys show that Teh is spot on in his observation.

The Edelman Trust Barometer 2018 report revealed that 63 percent of Malaysians could not distinguish between rumors and good journalism. A 2018 study by Ipsos, a global market research firm based in France, found that 50 percent of Malaysians admit they had discovered stories to be fake after they believed them to be true.

Malaysia’s Communications and Multimedia Minister Saifuddin Abdullah pointed out that there exists a demand-and-supply situation when it comes disinformation. “That, in turn, caused the deliberate spread of ‘fake news’, fraud and denials, to the extent that there are some people who seem to live in a parallel or fictional universe,” he told Bernama, the Malaysian national news agency.

For Teh, news users who fall for ‘fake news’, a phrase used to describe misinformation and disinformation, lack news and media literacy. The lack of such skills, the former journalist says, is why misinformation spreads widely.

Lucinda Joseph, a senior lecturer on online journalism and film at Inti College, agrees that some Malaysians cannot differentiate between news and ‘fake news’. “Most can’t because they don’t rely on a credible news site for information. Their primary source of news is from social media,” she said.

The traditional media are not a source of news for the younger generation because “they grew up getting information from social media,” Joseph said. Younger audiences are aware that ‘fake news’ exist on social media and messaging apps, she explains. “But they are not going to suddenly change and depend more on traditional media for their news feed,” she said.

In the early days of COVID-19, for example, a piece of misinformation that went viral was one that said hot water could protect people from the virus.

This became contagious. “A journalist told an online forum I organised for my students that her dad forwarded the message to all his family members without fact-checking,” said Joseph, a former broadcast journalist.

Ironically, it was the traditional media that gave credence to this piece of misinformation. In March, the Malaysian Health Minister Dr Adham Baba claimed on RTM, a Malaysian public broadcaster, that the virus could not take heat and that warm water would flush it down to the stomach where digestive acid would then kill it off.

It was also the media that debunked the Health Minister’s ‘fake news’. It ran reports quoting health experts as saying there was no evidence to back such dubious claim.

But the MCMC points to an encouraging development, where many news organisations in Malaysia have experienced significant gains in readership and viewership over the last couple of years. “The news industry should continue to focus on high-quality journalism that builds trust and attracts greater audiences,” an MCMC spokesperson said.

Malaysians have more trust in traditional media compared to five years ago, says a 2019 Ipsos report on this topic. “Seventy-nine percent of Malaysians think newspapers and magazines have good intentions, trust the intentions of TV and radio, and for online news sources the figure is 70percent,” said the ‘Trust in Media: A Malaysian Perspective’ report.

That’s good news for journalism.

In debunking ‘fake news’, Teh said the media play a role in educating people on news literacy and stopping such items from spreading further. “The media serve as an essential source to check the authenticity of news because journalists verify the information before publishing it,” he said.

Yannik does his own verification. If the ‘news’ is doubtful, he says, he will doublecheck it with established media organisations.

“Probably because of my academic training, I make sure that my source of information is credible before I rely on it. Why must I trust information sent by a random person on WhatsApp?” Yannik said.

The vaccine for the infodemic around COVID-19 is good journalism.

(*Philip Golingai is a columnist for ‘The Star’ in Malaysia. This guest feature is part of Reporting ASEAN’s #fighttheinfodemic series.)