The headline of this article was updated to correct the label from “FACT CHECK” to “FACT SHEET”.

The Office of the Ombudsman has issued new guidelines in releasing copies of Statement of Assets, Liabilities and Net Worth (SALN) more than one year after it suspended the processing of all requests from the media and the public.

Under Section 17 Article XI of the 1987 Constitution, public officials and employees are required to submit sworn SALN, a document containing details about personal properties, financial connections, and indebtedness of the filer, among others.

The new guidelines are more restrictive under Memorandum Circular No. 1, Series of 2020 that Ombudsman Samuel Martires signed on Sept. 1. It cited guiding provisions of the implementing rules and regulations (IRR) of Republic Act (RA) 6713, the Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees.

The memorandum will take effect on Sept. 25, or 15 days after it was published on Sept. 10 in a national newspaper and submitted for filing to the University of the Philippines Law Center.

However, former senator Joey Lina, author of RA 6713, questioned the new guidelines for being unconstitutional. In an interview on ANC, Lina said that in accessing SALNs “the higher (interest) must prevail and that’s the interest of the public…that’s primordial, the constitutionally guaranteed right of people to have access to public information.”

Here are the changes you need to know in the policy of the Office of the Ombudsman regarding SALN of public servants:

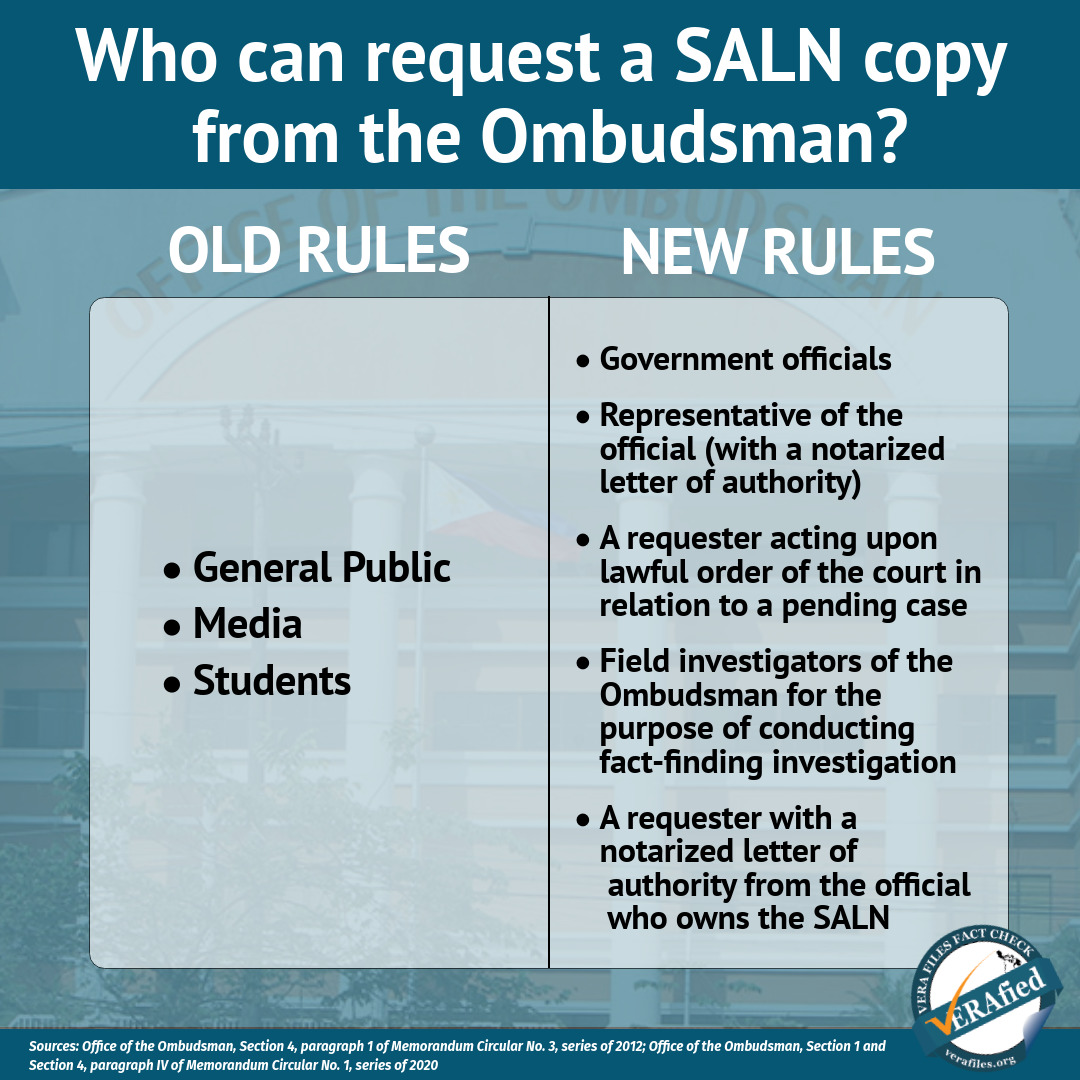

1. Who can request a copy of SALN?

In the old guidelines, people requesting SALNs from the Ombudsman just need to properly fill out the prescribed form and submit identification documents to the authorized staff.

Under the new guidelines, the Ombudsman has a list of authorized persons, such as the Ombudsman’s field investigators, government officials and their duly authorized representatives, who can request for SALN copies.

Persons who do not fall under any of the categories in the list will have to submit a notarized letter of authority from the official whose SALN is being requested.

Government agencies requesting copies of the SALNs of their officials and employees also have to submit a notarized authorization letter from those concerned.

RA 6713, the enabling law of the constitutionally mandated submission of SALN, did not limit access to SALNs in the Office of the Ombudsman and other custodians.

Although it set grounds to deny requests, RA 6713 and its implementing rules and regulations said that a SALN shall be made available to the public “for inspection at reasonable hours” once available for reproduction or still available subject to the 10-year period before the Ombudsman is allowed to destroy it.

In a 2012 decision on requests to access SALNs of its justices, the SC reminded that custodians have no authority “to prohibit access, inspection, examination, or copying of the [public] records” despite having the discretion to regulate the manner in which records may be inspected, examined or copied by interested persons.

The high court said: “However, custodians of public documents must not concern themselves with the motives, reasons and objects of the persons seeking access to the records. The moral or material injury which their misuse might inflict on others is the requestor’s responsibility and lookout. Any publication is made subject to the consequences of the law.”

2. What are the grounds to deny requests to access SALN?

Section 5 of RA 6713 states that all requests to government offices need to be addressed and replied within 15 days from the date of receipt, or they will face administrative disciplinary action.

Under the old rules, each request should be processed in just 60 minutes. The Ombudsman has yet to announce if it will adopt the same procedures.

3. Where to file and who processes the request?

The Ombudsman made significant changes on where to file and who shall process requests for SALN.

New requests shall now be filed with the Central Records Division (CRD) of the Ombudsman Central Office or the Case Records Evaluation, Monitoring and Enforcement Bureaus (CREMEB) of the Deputy Ombudpersons for Luzon, Visayas and Mindanao whichever serve as the official repository of the SALN of the official being requested.

According to RA 6713, the offices of the Ombudsman and its deputies serve as the SALN repositories for the president, vice president, heads of the constitutional commissions, and military officers below the rank of colonel or naval captain. (See VERA FILES FACT SHEET: Three things you must know about requesting SALNs from the Ombudsman)

However, other officials such as senators and congressmen, Supreme Court (SC) justices, and military officers from and above the colonel or naval captain ranks are required to submit their SALNs to different custodians, such as the secretaries of the House of Representatives and the Senate, clerk of court of SC, and the Office of the President, respectively. Requests to access the SALNs of these officials are subject to different guidelines set by their own repository agencies. (See VERA FILES FACT SHEET: SALNs, FOI in Congress explained)

Unlike in the old rules when the process of managing and approving SALN requests happen within the Public Assistance Bureau (PAB) of the Ombudsman, this time the officers at CRD or CREMEB are assigned to process and assess all SALN requests before submitting those to their respective office head for review. Under the new guidelines, the Ombudsman centralized approval of all SALN requests in the agency.

4. Why is access to SALNs important?

Access to public documents, such as SALNs, is a constitutional right of every Filipino. Making SALNs accessible adheres to the policy of transparency and accountability in government, and helps track or make a lifestyle check on public servants.

In the SALN, all public officials, including politicians, and government employees, except laborers and contractual workers, need to disclose under oath all of their assets (personal properties and monies, including cash on hand and in banks), liabilities (loans and debts), as well as business connections and financial interests, and relatives working also in government. The document must also contain all the business connections and interests of the officials’ spouse and unmarried minor children.

RA 6713 states that all SALNs must be submitted every year on April 30, and before assumption or leaving office. This year, however, the Civil Service Commission extended the submission twice from June 30 to Aug. 31 due to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

Non-declaration or misdeclaration of SALNs have already led to the ouster of two former chief justices: Renato Corona and Maria Lourdes Sereno. Corona was impeached in 2012 due to his failure to declare multi-million peso financial assets. Sereno was removed through a quo warranto petition due to non-filing of SALN when she was still a professor at the University of the Philippine College of Law.

Former president Joseph Estrada faced impeachment and was eventually charged with perjury in 2001 for falsely declaring his assets.

To uphold transparency in government, President Rodrigo Duterte signed Executive Order No. 2 in 2016 to “operationalize” the constitutional right to freedom of information of Filipinos. The EO mandates all offices under the executive branch to allow access to public documents, including SALNs, subject to existing laws and regulations. However, the executive branch was questioned in 2017 for releasing heavily redacted copies of SALNs of Duterte’s Cabinet members.

Duterte is being criticized by several groups and lawyers because his SALNs for 2018 and 2019 are yet to be made public due to the indefinite suspension of release by the Ombudsman since last year. His health records are also petitioned before the Supreme Court because the Office of the President denied requests for copies even as the president has been publicly talking about his ailments.

Enabling bills required by the Constitution that will operationalize freedom of information are still pending in Congress. At least seven bills have been filed in the Senate and 19 in the House of Representatives.

Editor’s note: The headline of this article was updated to correct the label from “FACT CHECK” to “FACT SHEET”.

Sources

Ombudsman, Memorandum Circular No. 1, Series of 2020, Sept. 1, 2020

Ombudsman, Memorandum Circular No. 3, Series of 2012, Sept. 11, 2012

Ombudsman, READY

Official Gazette, Republic Act No. 6713, Feb. 20, 1989

Civil Service Commission, Rules Implementing the Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees Pursuant to the provisions of Section 12 of Republic Act No. 6713

ABS-CBN News, Restriction of public access to SALNs unconstitutional: ex-senator | ANC, Sept. 17, 2020

Ombudsman, Memorandum Circular No. 1, Series of 2018, June 29, 2018

Official Gazette, Executive Order No. 2, s. 2016

Supreme Court, A.M. No. 09-8-6-SC, June 13, 2012

Office of the President, Exceptions to the Right to Access of Information. Nov. 24, 2016

Official Gazette, The 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines, Feb. 2, 1987

Civil Service Commission, File SALN before 31 August 2020; online submission accepted – CSC, June 25, 2020

Archive.org, Can Estrada Explain His Wealth?

World Bank Institute, Journalistic Legwork that Tumbled a President

Rappler, Corona found guilty, removed from office, May 29, 2012Official Gazette, Articles of Impeachment against Chief Justice Renato C. Corona (December 12, 2011) | GOVPH, Dec. 12, 2011

Sereno’s impeachment and oust

- House of Representatives, House panel OKs impeachment vs. Sereno, March 19, 2018

- House of Representatives, Statement of Speaker Pantaleon Alvarez on Supreme Court ruling in Sereno’s case, June 19, 2018

- ABS-CBN News Online, Sereno got P30-million Piatco case fee in tranches, only portion declared in 2010 SALN: lawyers, September 27, 2017

- ABS-CBN News Online, READ: The Supreme Court decision ousting Chief Justice Sereno, May 11, 2018

- ABS-CBN News Online, Supreme Court rules CJ Sereno ouster final, June 19, 2018

- Rappler.com, Sereno now has 11 U.P. SALNs on file, April 12, 2018

Executive branch questioned for heavily redacted SALNS

- ABS-CBN News, Unexplained wealth, redacted?, Sept. 23, 2017

- Rappler.com, Redactions in Duterte Cabinet’s latest SALNs ‘deal-breaker’ for FOI – PCIJ, Sept. 22, 2017

- Inquirer.net, Senators question redaction of Duterte Cabinet’s SALNs, Sept. 26, 2017

Petition to disclose Duterte’s health records

- GMA News Online, It’s final: Supreme Court denies lawyer’s petition for Duterte’s health records, Sept. 18, 2020

- Manila Bulletin, Ruling vs. disclosure of Duterte’s health, medical records final, says SC, Sept. 18, 2020

- ABS-CBN News, SC blocks with finality bid to disclose Duterte health records, Sept. 18, 2020

Senate of the Philippines, Pending freedom of information bills, Accessed Sept. 17, 2020

(Guided by the code of principles of the International Fact-Checking Network at Poynter, VERA Files tracks the false claims, flip-flops, misleading statements of public officials and figures, and debunks them with factual evidence. Find out more about this initiative and our methodology.)